uring the past few years, the global conversation about responsible technology has intensified. Increasingly, we are acknowledging that technology is not and can never be neutral, that it holds significant implications for people and society, and that intelligent technologies have consequences that can disenfranchise or target vulnerable populations.

None of this is news to historians of technology, sociologists, political scientists and others who study human behaviour and history. Yet, it seems nothing was further from the minds of the social media platforms’ founders when they conceived of their services. These tech giants’ products now act as the de facto communication channels for a significant portion — up to half — of the 4.3 billion internet users worldwide.

Even a brief glance at these companies’ websites1 offers a window into their conceptions of themselves. Facebook’s mission is “to give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together.”Twitter’s is “to give everyone the power to create and share ideas and information instantly without barriers.” YouTube aims “to give everyone a voice and show them the world.”

These companies have been woefully unprepared for the ways their platforms could be weaponized. Facebook, Twitter and YouTube were used to distribute and amplify misinformation in both the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and the 2016 presidential election in the United States.2

They were used to livestream the terror attacks on two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand.3 They’ve been used as a tool for ethnic cleansing in Myanmar (Mozur 2018). White supremacists and other similar groups regularly use them to spread hate speech.

What should we take into account in order to develop governance structures that work for social media platforms?@setlinger lists the factors we must consider: pic.twitter.com/r8pHvd9EuQ

— CIGI (@CIGIonline) November 7, 2019

Clearly, these effects stand at odds not only with democratic values but with the platforms’ stated intentions and ideals. In response, the companies have instituted or augmented existing fairness, trust and safety teams to address these issues organizationally and systemically. They’ve built principles and checklists and thick, detailed volumes of community guidelines. They’ve contracted with companies that employ thousands of moderators around the world to review content.

Still, the incidents continue. Given the threats to democracy and society, as well as their considerable resources and technical capability, what exactly is preventing social media companies from more effectively mitigating disinformation, hate speech and aggression on their platforms?

Addressing these issues is not as straightforward as it seems. In addition to the legal, social and cultural dynamics at play, there are other factors we must consider: the scale of social media platforms; the technologies on which they are built; and the economic environments in which they operate. Any one of these factors alone would present significant challenges — the scale of operations, the sophisticated yet brittle nature of intelligent technologies and the requirements of running publicly traded companies — but in concert they prove far more complex.

The Scale of Social Media

The scale of social media today is unprecedented. For example, in contrast to the early days — when Facebook was created as a site to rate women’s attractiveness, before it morphed into a kind of digital yearbook — the company today has 2.41 billion monthly active users (as of June 30, 2019), and “more than 2.1 billion people use Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, or Messenger every day on average.”4 YouTube has over one billion users — comprising approximately one-third of internet users — and operates in 91 countries in 80 different languages. According to YouTube, people around the world watch over a billion hours of video every single day. Twitter has 139 million daily active users, who send 500 million tweets per day. All these numbers add up to a level of impact and complexity in communications that has never before been seen in human history.

Understanding the Technology Issues

Social media platforms today are far more technically sophisticated than when they were introduced in the mid 2000s. One of the key changes is the use of what are broadly referred to as artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, which enable the platforms to recognize and interpret language and images and use data to develop models that draw inferences, classify information and predict interests, among other things.

These capabilities enable the platforms to recommend videos, products or political posts to us, translate posts from languages different from our own, identify people and objects, and provide accessibility options to people with visual impairments or other needs. They can also be used to identify potentially problematic content or account behaviour.

What’s fundamentally different about these technologies is that, unlike computer programs of the past, AI learns from data and behaves autonomously in some circumstances. But, as sophisticated as they are becoming, intelligent technologies pose serious trade-offs. There are several core issues at play.

Safety versus Freedom of Speech

When it comes to content moderation, AI programs are not adept at understanding context and nuance, so they make mistakes that can result in “false positives” (flagging an innocuous video, statement or photo) or “false negatives” (missing a violent or otherwise undesirable post). In the world of social media, false positives prompt protests over censorship, for example, when a platform removes a post by an organization that is sharing it to raise awareness of a human rights violation, while false negatives expose the company to legal liability, if, say, it fails to recognize and remove prohibited content within a stipulated time period.

As a result, social media companies use human content moderators to review ambiguous posts, a task some have dubbed “the worst job in history” (Weber and Seetharaman 2017). Content moderators, often employees of large contracting firms, watch and classify hundreds of thousands of posts per day. Some of the tasks, such as labelling places and classifying animals, are generally harmless, if rather tedious, but the people who deal with the most extreme content can develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress triggered by ongoing exposure to disturbing imagery. Some content moderators, after repeated exposure to certain material, begin to “embrace the fringe viewpoints of the videos and memes that they are supposed to moderate” (Newton 2019).

Bias, implicit or explicit, tends to become amplified. One person’s protest is another person’s riot.

The essentially subjective, probabilistic and often culturally specific nature of image and language classification creates additional complexity. Bias, implicit or explicit, tends to become amplified (Zhao et al. 2017). One person’s protest is another person’s riot. One person’s treasured photo of a family member breastfeeding her child is another person’s pornography.

Facebook’s 2016 removal of “Napalm Girl,” Nick Ut’s historic and Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of a naked nine-year-old girl, Kim Phúc, screaming in pain as she fled a napalm attack during the Vietnam War, highlights both the contextual nature of media and the constraints of algorithmic decision making. Facebook’s decision to remove the photo prompted an open letter to the company in Aftenposten, Norway’s largest newspaper, charging the company with censorship and abuse of power (Hansen 2016). Facebook countered, “While we recognize that this photo is iconic, it’s difficult to create a distinction between allowing a photograph of a nude child in one instance and not others” (quoted in Levin, Wong and Harding 2016). Ultimately, the company reinstated “Napalm Girl.”

But Facebook’s argument cannot be viewed as an isolated editorial choice; it’s a systems issue as well. The algorithms that the company uses to moderate content learn from decisions, so social media platforms must also consider the precedents they are setting in their systems, what unintended and undesirable consequences such decisions might unleash, and what possible technical interventions could prevent those unwanted consequences from occurring in the future, all across dozens of languages, multiple varieties of data (text, photo, meme, video) and millions of posts per day.

Limitations of Language Technologies

While language technology continues to improve rapidly, it remains highly dependent on high volumes of labelled and clean data to achieve an acceptable level of accuracy. “To determine in real-time whether someone is saying something that suggests a reasonable likelihood of harm,” says Carole Piovesan, partner and co-founder of INQ Data Law, “requires a team of local interpreters to understand the conversation in context and in the local dialect.”5 From a practical standpoint, it is much easier for algorithms and content moderators to interpret a fast-moving event in a language spoken by hundreds of millions of people than it is to interpret content in a language or dialect spoken by a small population.

This type of scenario also requires a process to ensure that there is consensus on the meaning of and action to be taken on a questionable post — a process that is critical but time-consuming in situations where even milliseconds can determine how far a message will spread. This makes it difficult, if not impossible, for social media companies to comply with laws that require removal of prohibited posts within the hour. Furthermore, as Piovesan points out, there are secondary effects we must consider: “If you were to offer your service only in those regions where you have enough competent interpreters to properly understand the conversation, you risk increasing the divide between those who have access to social platforms and those who do not.”

Lack of Digital Norms

Social networks now find themselves having to make decisions, often imperfect ones, that affect people across the world. It would be far simpler for them to establish a common culture and set of norms across their platforms. But, says Chris Riley, director of public policy at Mozilla, “that would be very hard to do without meeting the lowest common denominator of every country in which they operate. It’s not possible to engineer a social network that meets the social expectations of every country. Furthermore, it’s not advisable to try, because to do so would promote cultural hegemony.”6 This does not mean that it is fruitless for the global community to attempt to agree upon governance structures. Rather, these structures must be flexible enough to account for language, culture, access, economic and other variables without introducing undesirable unintended consequences.

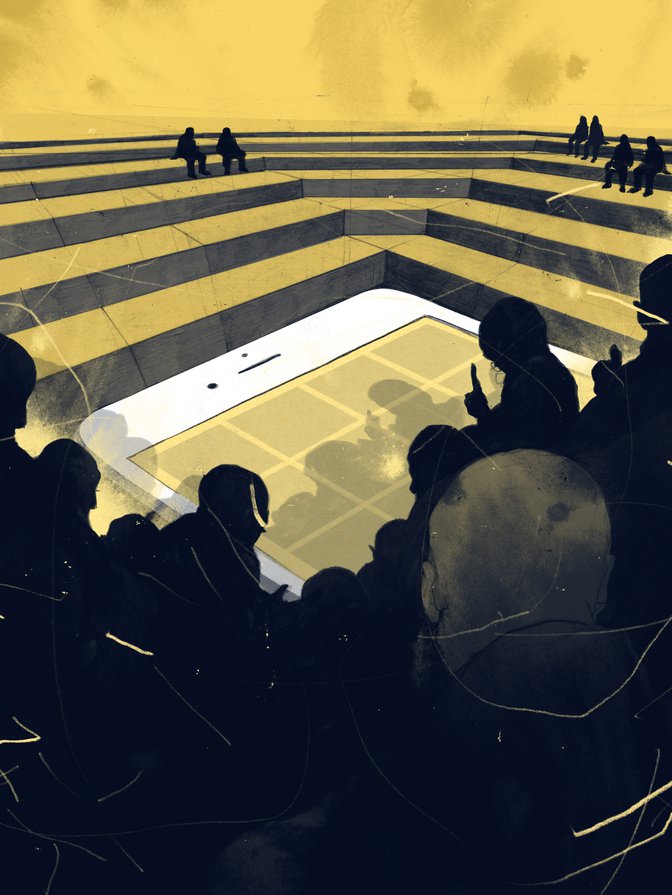

The Economics of Social Media Companies

Social media companies’ mission statements focus on sharing, community and empowerment. But their business models are built on, and their stock prices rise and fall every quarter on the strength of, their ability to grow, as measured in attention and engagement metrics: active users, time spent, content shared.

But this isn’t simply a question of profit. The large social media companies — Facebook (including Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp), Twitter and YouTube (owned by Google) — are publicly traded. They must meet their responsibility to society while also upholding their fiduciary responsibility to shareholders, all while navigating a complex web of jurisdictions, languages and cultural norms. By no means does this excuse inaction or lack of accountability. Rather, it illustrates the competing access needs of a wide range of stakeholders and the dynamics that must inform governance structures in the digital age.

Considerations for Global Platform Governance

The realities of scale, technology and economics will continue to challenge efforts to implement practical and effective governance frameworks. The following are a few ideas that warrant further discussion from a governance perspective.

Secure Mechanisms for Sharing Threat-related Data

We will continue to see bad actors weaponize the open nature of the internet to destabilize democracy and governments, sow or stifle dissent and/or influence elections, politicians, and people.7 Technologies such as deepfakes (O’Sullivan 2019) and cheapfakes (Harwell 2019) will only make it harder to distinguish between legitimate content and misinformation. We’ll also see human (troll) and bot armies continue to mobilize to plant and amplify disinformation, coordinate actions across multiple accounts and utilize “data voids” (Golebiewski and boyd 2018) and other methods to game trending and ranking algorithms and force their messages into the public conversation.

As we have seen, this behaviour typically occurs across multiple platforms simultaneously. A sudden increase on Twitter in the number and activity of similarly named accounts in a particular region may be a precursor to a campaign, a phenomenon that could also be occurring simultaneously on Facebook or another social network.

But, as in the cyber security world, social media platforms are limited in the extent to which they are able to share this type of information with each other. This is partially a function of the lack of mechanisms for trust and sharing among competitors, but, says Chris Riley, “it’s also hard to know what to share to empower another platform to respond to a potential threat without accidentally violating privacy or antitrust laws.” In effect, this limitation creates an asymmetric advantage for bad actors, one that could potentially be mitigated if social media platforms had a secure and trustworthy way to work together.

Third-party Content Validation

One approach that has been discussed in policy circles is the idea of chartering third-party institutions to validate content, rather than having the social media platforms continue to manage this process. Validation could potentially become the responsibility of a non-partisan industry association or government body, leaving platforms to focus their resources on account behaviour, which is, generally speaking, less subjective and more tractable than content.

Viewing Takedowns in Context

The outcry over Facebook’s 2016 decision to remove the “Napalm Girl” image from its platform illustrates why it’s so important to look at content takedowns not in isolation but in context. Looking at them in context would require understanding the reason for removing the content: whether it was a purely automated or human-influenced decision, the policies according to which the platform took that decision, the speed at which it was accomplished and the available appeals process. As fraught and newsworthy as content takedowns may sometimes be, it’s neither productive nor sustainable to view them in isolation. Rather, governance structures should examine the organization’s commitment to responsibility over time as evidenced by process, policy, resource allocation and transparency.

Conclusion

As we consider governance frameworks to address the issues presented by social media, we must also consider their implications for broader business and social ecosystems and, to the extent possible, plan for the emergence of technologies that will present novel challenges and threats in the future. These plans will require a measure of flexibility, but that flexibility is critical to ensure that we become and remain equal to the task of combatting disinformation, protecting human rights and securing democracy. Whatever path we choose, one thing is clear: the global digital governance precedents we set for social media today will affect us, individually and collectively, far into the future.