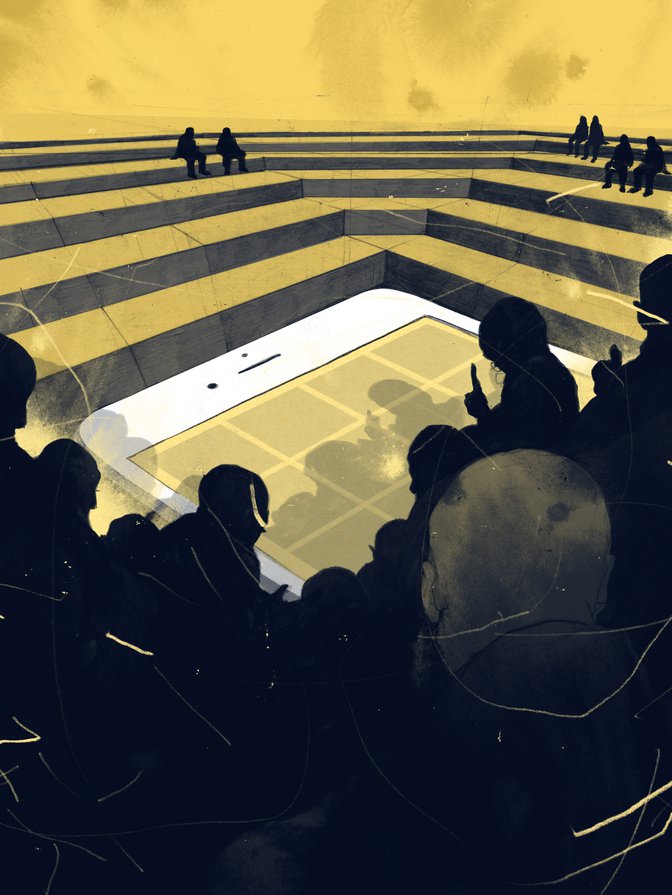

ommercial journalism is failing in many countries around the world.1 Numerous factors contribute to this crisis, but at its root lies a “systemic market failure” in which for-profit news institutions, in particular those that depend on advertising revenue, are increasingly unviable. Symptomatic of this broader decline, traditional news organizations’ cost-cutting measures are depriving international news operations of the considerable resources they need to survive. In recognition of this systemic failure, a healthy global civil society requires structural alternatives — specifically, non-market models — to support adequate levels of journalism. In particular, we need a large global trust fund to finance international investigative reporting. Given their role in hastening the decline of journalism and proliferating misinformation, platform monopolies should contribute to this fund to offset social harms. While setting up such a fund will be novel in many respects, there are models and policy instruments we can use to imagine how it could support the public service journalism that the market no longer sustains.

The Broader Context

As commercial journalism collapses around the world, a glaring lesson comes into focus: no commercial model for journalism can adequately serve society’s democratic needs. To be more specific, no purely profit-driven media system can address the growing news deserts that are sprouting up all over the United States and beyond, or fill the various news gaps in international coverage. If we come to see systemic market failure for what it is, we will acknowledge that no entrepreneurial solution, no magical technological fix, no market panacea lies just beyond discovery. While subscription and membership models might sustain some relatively niche outlets and large national and international newspapers such as The New York Times and The Guardian, they do not provide a systemic fix. In particular, they cannot support the public service journalism — the local, policy, international and investigative reporting — that democratic society requires. Commercial journalism’s structural collapse has devastated international news at a time when global crises are worsening — from climate change to growing inequalities to fascistic political movements. At perhaps no other time has the need for reliable, fact-based and well-resourced journalism been more acute.

The social harms of Facebook’s monopoly power is especially apparent in how it corrupts the integrity of our news and information systems.

Coinciding with the precipitous decline of traditional news media, platform monopolies — Facebook most notably — are attaining levels of media power unprecedented in human history. So far, this power has been largely unaccountable and unregulated. As Facebook extracts profound wealth across the globe, it has generated tremendous negative externalities by mishandling users’ data, abusing its market power, spreading dangerous misinformation and propaganda, and enabling foreign interference in democratic elections (Silverman 2016; Vaidhyanathan 2018). It has also played a key role in destabilizing elections in places such as the Philippines and in facilitating ethnic cleansing in Myanmar (Stevenson 2018). In short, Facebook has hurt democracy around the world. Considering the accumulating damage it has wreaked and the skewed power asymmetry between Facebook and its billions of users, we need a realignment.

The social harms of Facebook’s monopoly power is especially apparent in how it corrupts the integrity of our news and information systems. As an algorithm-driven gatekeeper over a primary information source for more than two billion users, Facebook wields tremendous political economic power. In the United States, where Americans increasingly access news through the platform, Facebook’s role in the 2016 presidential election has drawn well-deserved scrutiny. Moreover, along with Google, Facebook is devouring the lion’s share of digital advertising revenue and starving the traditional media that provide quality news and information — the same struggling news organizations that these platforms expect to help fact-check against misinformation (Kafka 2018). Journalism’s financial future is increasingly threatened by the Facebook-Google duopoly, which in recent years took a combined 85 percent of all new US digital advertising revenue growth, leaving only scraps for news publishers (Shields 2017). According to some calculations, these two companies control 73 percent of the total online advertising market.2 Given that these same companies play an outsized role in proliferating misinformation, they should be bolstering — not starving — news outlets.

Despite the lack of silver-bullet policy solutions, this moment of increased public scrutiny offers a rare — and most likely fleeting — opportunity to hold an international debate about what interventions are best suited to address these informational deficits and social harms. Ultimately, these problems necessitate structural reforms; they cannot be solved by simply shaming digital monopolies into good behaviour or by tweaking market incentives. With platform monopolies accelerating a worldwide journalism crisis, a new social contract is required that includes platform monopolies paying into a global public media fund.

Taxing Digital Monopolies and Redistributing Media Power

Platform monopolies have not single-handedly caused the journalism crisis — overreliance on market mechanisms is the primary culprit — but they have exacerbated and amplified communication-related social harms. Beyond regulating and penalizing these firms, we should require that they help undo the damage they have caused. Not only do these firms bear some responsibility, but they also have tremendous resources at their disposal. Despite a general unease about policy interventions in this arena — especially in the United States where a combination of First Amendment absolutism and market fundamentalism render many policy interventions off-limits — scholarship has long established that media markets produce various externalities (see, for example, Baker 2002). It is the role of government policy to manage them — to minimize the negative and maximize the positive externalities for the benefit of democratic society. Even the relatively libertarian United States redistributes media power with public access cable channels, the universal service fund and subsidized public broadcasting, to name just a few examples. Policy analysts also have proposed various schemes for taxing platforms in the US context.3

Internationally, policy makers and advocates have proposed a number of similar models. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Media Reform Coalition and the National Union of Journalists proposed allocating capital raised from taxes on digital monopolies to support public service journalism. Jeremy Corbyn echoed this plan by calling for digital monopolies to pay into an independent “public interest media fund” (Corbyn 2018). Similarly, the Cairncross Review, a detailed report on the future of British news media, called for a new institute to oversee direct funding for public-interest news outlets (Waterson 2019).

While these various proposals for national-level media subsidies are encouraging, the international scope of this problem requires a global public media fund. One proposal has called for establishing a $1 billion4 international public interest media fund to support investigative news organizations around the world, protecting them from violence and intimidation (Lalwani 2019). According to this plan, the fund would rely on capital from social media platforms as well as government agencies and philanthropists.

Platforms should devote a small % of their annual profits towards supporting a global, independent public media fund.

— CIGI (@CIGIonline) November 2, 2019

Why? Turn your sound on to listen to @VWPickard explain 🔊 pic.twitter.com/rkxZUuaYAH

Platform monopolies should not be solely responsible for funding global public media, but the least they could do is support the investigative journalism, policy reporting and international news coverage that they are complicit in undermining. Thus far, Google and Facebook have each promised $300 million over three years for news-related projects. Google has pledged this money toward its News Initiative,5 and Facebook has sponsored several projects, including its $3 million journalism “accelerator” to help 10–15 news organizations build their digital subscriptions using Facebook’s platform (Ingram 2018). Another program, Facebook’s “Today In” app section, aggregates local news in communities across the United States, but it ran into problems when Facebook found many areas already entirely bereft of local news (Molla and Wagner 2019). More recently, Google has announced that it would tailor its algorithms to better promote original reporting (Berr 2019), and Facebook has promised to offer major news outlets a license to its “News Tab” that will feature headlines and article previews (Fussell 2019). Nonetheless, these initiatives are insufficient given the magnitude of the global journalism crisis — efforts that one news industry representative likened to “handing out candy every once in a while” instead of contributing to long-term solutions (quoted in Baca 2019).

Redistributing revenue toward public media could address the twin problems of unaccountable monopoly power and the loss of public service journalism. Facebook and Google (which owns YouTube) should help fund the very industry that they both profit from and eviscerate. For example, these firms could pay a nominal “public media tax” of one percent on their earnings, which would generate significant revenue for a journalism trust fund (Pickard 2018). Based on their 2017 net incomes, such a tax would yield $159.34 million from Facebook and $126.62 million from Google/Alphabet. Together, this $285.96 million, if combined with other philanthropic and government contributions over time, could go a long way toward seeding an endowment for independent journalism. A similar, but more ambitious, plan proposed by the media reform organization Free Press calls for a tax on digital advertising more broadly, potentially yielding $2 billion per year for public service journalism (Karr and Aaron 2019, 8). These firms can certainly afford such expenditures, especially since they pay precious little in taxes.

Redistributing revenue toward public media could address the twin problems of unaccountable monopoly power and the loss of public service journalism.

In countries around the world, there is a growing consensus that digital monopolies should be sharing their wealth, conceding to public oversight and taking on more responsibilities for the social harms they have caused. Increasingly, these presumed responsibilities include protecting sources — and providing resources — for reliable information. Although calls for taxing these firms have yet to succeed in any significant way, they reflect rising awareness about the connections between digital monopolies’ illegitimate wealth accumulation, the continuing degradation of journalism and the rise of misinformation. If we are to grant platform monopolies such incredible power over our vital communication infrastructures, we must have a new social contract to protect democratic society from social harms.

From Theory to Action

Creating an independent public international media fund does not end with procuring sufficient resources. Once the necessary funding is in place, we have to ensure these new journalistic ventures operate in a democratic manner. We must establish structural safeguards mandating that journalists and representative members of the public govern them in a transparent fashion in constant dialogue with engaged, diverse constituencies. These funds should go to the highest-need areas, with key allocations decided democratically via public input through an international body. These resources might support already-existing organizations such as the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and the International Consortium of Investigative Reporting, or they might help create entirely new outlets. Whether this body is housed at the United Nations or some new institution, we must start pooling resources and imagining what this model might look like.

No easy fix will present itself for journalism — or for the tremendous social problems around the world — but a well-funded, international and independent public media system is a baseline requirement for tackling the global crises facing us today. It is urgent that we begin the serious conversations needed to create this fund now and move quickly into action.