uring the summer of 2019, the mass shooting in El Paso, Texas — the gunman apparently spurred on by online hate and troll community 8chan (Roose 2019) — reignited calls for online social media platforms to take down harmful content. In response to pressure, the intermediary site Cloudflare dropped its protection of 8chan (Newman 2019), only the second time in the service’s questionable history that it has deplatformed one of its clients (the first being white supremacy site the Daily Stormer, following the fatal protests in Charlottesville in August 2017) (Klonick 2017). A few months later, in a dance that has become depressingly familiar over the last four years, conservative members of the US Congress demanded that platforms uphold free speech and not be allowed to wantonly “censor” certain types of content (Padhi 2018).

This tension is nothing new. The difficulty of preserving private companies such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube as open platforms that support freedom of expression, while also meeting real-world concerns and removing harmful content, is as old as the internet itself. And while activists, scholars, government and civil society have called on platforms to be more accountable to their users for decades,1 the feasibility of creating some kind of massive global stakeholder effort has proved an unwieldy and intractable problem. Until now.

On September 17, 2019, after nine months of consultation and planning, Facebook announced that it would be jettisoning some of its power to regulate content to an independent external body called the “Oversight Board” (Harris 2019). Described unofficially by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg as a “Supreme Court” of Facebook in interviews in early 2018, the board is now imagined as a body to serve in an oversight capacity for Facebook’s appeals process on removal of user content, as well as in a policy advisory role (Klein 2018). Having concluded their period of consultation and planning, Facebook says that the board will consist of 11–40 members, who will issue binding decisions on users’ content removal appeals for the platform, and issue recommendations on content policy to Facebook (ibid.).

.@Klonick: Whether or not #Facebook’s Oversight Board will be successful is a big question.

— CIGI (@CIGIonline) November 4, 2019

Learn more by visiting https://t.co/MMzgGNYGAw pic.twitter.com/F2E528oxOl

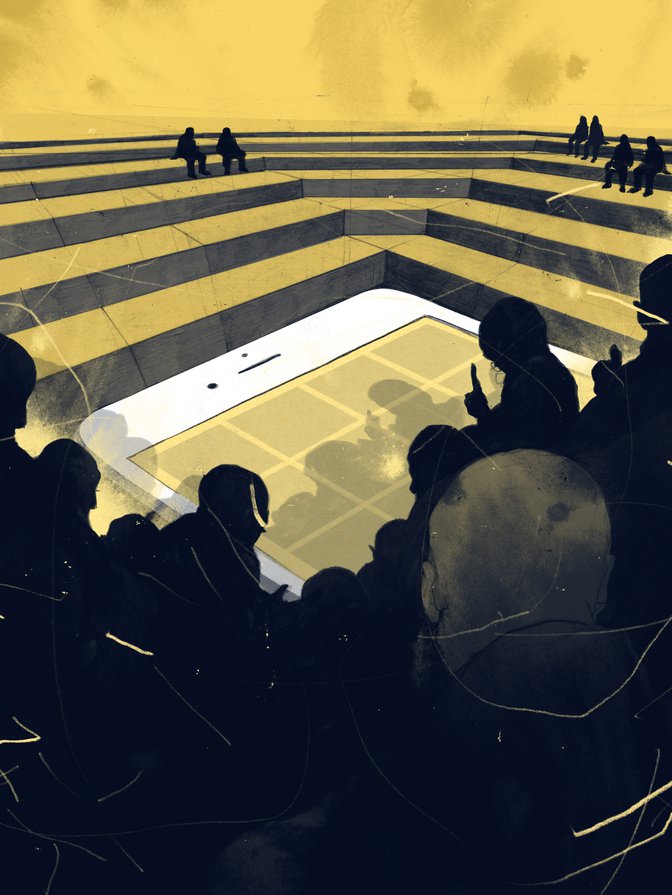

The creation of the board comes after more than a decade of agitation from civil society, users and the press to create a more accountable mechanism for platform content moderation. Platform policies around content moderation have high stakes because they involve the private governance of an essential human right — speech. Trying to build a more “publicly” accountable system means not only developing an appellate procedure through which users can seek re-review of removed content, but also finding a way for them to voice displeasure with existing policies and their enforcement.

But creating legitimacy around such a board — given that it originates with the entity it is supposed to be checking — is no easy task. It requires careful and deliberate thought around how to actually design and implement an independent adjudicatory board, how to ensure meaningful transparency, how to generate reasoned explanations for decisions, and how to perpetuate such a system into the future and guard against its capture by Facebook or other outside groups — or worse, impotence.

Essential to the board’s gaining legitimacy as a public-private governance regime is others’ perception of it as independent. Right, now the board’s independence comes from two places. Financially, a third-party foundation will be given an irrevocable initial endowment by Facebook; that trust will operate independently to pay salaries and organizational costs for the board. Substantively, the board is in charge of its own “docket” or case selection (except in extreme circumstances where Facebook asks for expedited review on a piece of content), investigations and decisions. Moreover, a board member can’t be removed for their vote on a particular content question, only for violating a code of conduct. These factors to preserve independence certainly aren’t perfect, but they’re more robust firewalls than Facebook has implemented in the past.

One of the other elements in creating legitimacy is developing a public process that incorporates listening to outside users and stakeholders into developing what the board would look like. In a series of six large-scale workshops around the world, dozens of smaller town halls, hundreds of meetings with stakeholders and experts, and more than 1,000 responses from an online request for public input, the Facebook team creating the infrastructure and design of the board listened to 2,000 external stakeholders and users in 88 languages about what they wanted from it, how it should look and how it should be built. Then the team published all that feedback in a 44-page report, with 180 pages of appendices, in late June 2019 (Facebook 2019a; 2019b). The report spelled out the panoply of questions inherent in making such an oversight body.

Those individuals must be guided by binding documents such as the charter and principles that structurally and procedurally incorporate transparency, independence and accountability.

The release of the board’s charter2 reflects the work of this massive global consultancy that took place over six months. It also finally provided some answers and details on the trade-offs Facebook has decided to take in constructing the board.

Listening to outside voices and preserving the board’s independence in both financial structure and subject matter jurisdiction help to ensure legitimacy, but perhaps one of the most vital pieces of establishing that the board would not be merely a toothless body was specifying how the board’s decisions would interact with the decisions of Facebook.

This dynamic is one of the most significant points covered in the charter — how the board’s decisions will be binding on Facebook — a major point of contention throughout the six-month consultancy with outsiders. Many in workshops and feedback fora thought the board’s views ought to have a binding effect on Facebook’s policy about what speech stayed up or came down on the platform. Others argued that the board having that much power was no better than Facebook having it — and that enacting those decisions online would be impractical to implement from an engineering perspective. Ultimately, the compromise made was that Facebook is to be bound by all decisions by the board on individual users’ appeals. However, and perhaps most significantly, although the board can only recommend policy changes to Facebook, the company is required to give a public explanation as to why it has or has not decided to follow that recommendation.

Although Facebook is not under a mandate to take up the board’s recommendations, neither can the platform just autocratically avoid transparency and accountability in deciding not to follow such policy recommendations from the board. Instead, it must furnish reasons — and, one assumes, good reasons — for deciding not to take up a recommendation of the board, and publish those reasons. The mandate of transparency creates an indirect level of accountability through public pressure — or “exit, voice, and loyalty”3 — traditional measures of popular opposition to power structures private or public. While not perfect, this arrangement allows the public much more access and influence over content moderation policy than users have ever had before.

The charter has answered a lot of questions, but also highlights some key ones remaining, among them who will serve. The subject was actively debated at workshops and drew feedback from outside stakeholders. Perhaps unsurprisingly, generally people felt that the board should be diverse, but in making specific recommendations, they seemed to believe that the board should reflect themselves. International human rights experts felt all board members should have a background in international human rights; lawyers felt that all board members should be legally trained or even all be judges. Ultimately, the charter envisions a board of 40 people at most who will meet certain professional qualifications — “knowledge,” “independent judgment and decision making” and “skill[s] at making and explaining decisions” — while also bringing diverse perspectives.

Precisely who is on the first oversight board will no doubt be incredibly important: inaugural members will set the norms for what the board does and how it functions. But names alone will not secure the board’s success or establish its legitimacy. While legitimacy can surely be helped along by a board whose members are judicious, even-handed, fair-minded and well-reasoned, those individuals must be guided by binding documents such as the charter and principles that structurally and procedurally incorporate transparency, independence and accountability. All these things together will determine the legitimacy of the board, and that process will not begin until users see Facebook make decisions recommended or mandated by the board that are in users’ interests but against the company’s immediate best interests. Those choices to act are up to Facebook, but the second part is up to all of us. This is where users expressing their exit, voice or loyalty responses to Facebook becomes more important than ever. The board is not perfect, but it is a potentially scene-changing leverage point for accountability. As we hurtle forward in this new land of private platform governance, we as users can’t afford to let such opportunities for accountablility languish.