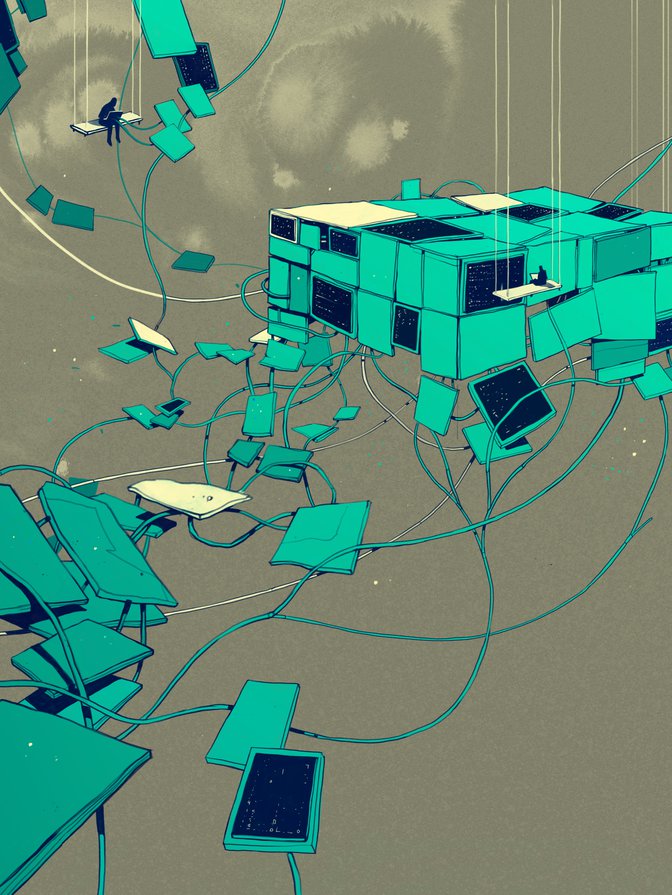

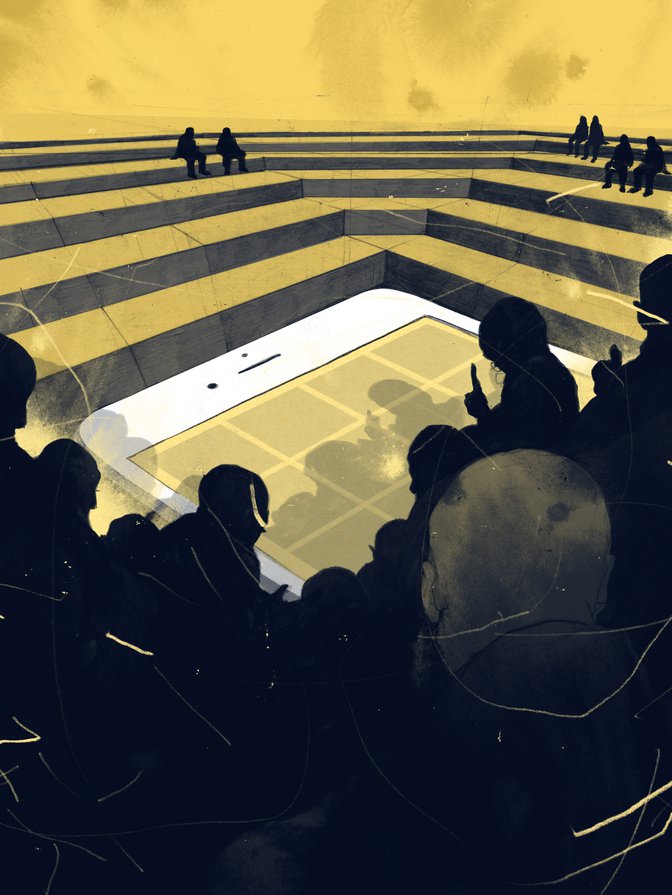

latforms are at the core of the digital economy. They form its backbone and are its conduits. They are used for search, social engagement and knowledge sharing, and as labour exchanges and marketplaces for goods and services. Activities on platforms are expanding at a tremendous pace that is likely to continue, especially with 5G implementation looming. Platforms such as Google, Facebook, Twitter and Amazon span the globe, serve billions of users and provide core functions of our society, analogous to the role served by public utilities. But the governance around their functions is not well developed as it is for public utilities. In fact, there is a governance chasm.

Indeed, while platforms are pervasive in everyday life, the governance across the scale of their activities is ad hoc, incomplete and insufficient. They are a ready and often the primary source of information for many people and firms, which can improve consumer choice and market functioning. Yet, this information may be inaccurate, by design or not, and used to influence the actions of individuals — and, recently, the outcomes of elections. Their operations are global in scope, but regulation, the little that exists, is domestic in nature. They help to facilitate our private lives, but can also be used to track and intrude into our private lives. The use of private data is opaque, and the algorithms that power the platforms are essentially black boxes. This situation is unacceptable.

Indeed, while platforms are pervasive in everyday life, the governance across the scale of their activities is ad hoc, incomplete and insufficient.

To be sure, there are many governance initiatives under way. Some countries are developing national strategies for artificial intelligence (AI) and big data. Some are examining and developing policy responses to the issue and implications of fake news. Several are developing national cyber strategies. Many are revisiting and revising legislation around privacy. The Group of Seven and the Group of Twenty (G20) have begun some initiatives, as have the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations. Even the platforms themselves have called for some form of regulation.

But as yet there is no comprehensive global discussion or action. Governance innovation is required to create an integrated framework at the national and international levels. This framework needs a broad combination of policies, principles, regulations and standards, and developing it will involve experimentation, iteration and international coordination, as well as the engagement of a wide variety of stakeholders.

The Current Situation Has Been Seen Before

In some senses, the current situation is reminiscent of the rapid development of financial services globally in the 1990s and 2000s. Fuelled by light-touch regulation, and in no small measure by hubris, banks grew in size and power, leading to some exceptionally large global banks. In many instances, this expansion was encouraged by the prevailing notion that it was a global good, creating new financial services for new customers with greater efficiency, via financial wizardry that turned out to be opaque in terms of network effects, risks and consequences. The view then was that self-interest and reputation would constrain bad behaviour.

Sound familiar? We witnessed the significant social consequences that resulted, and the plummet in the public’s trust in institutions.

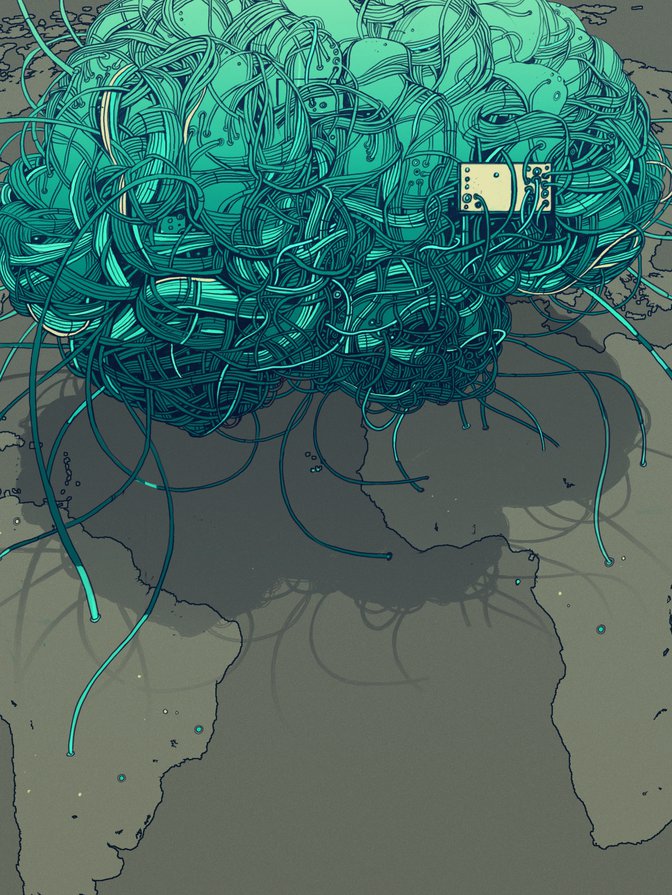

The current regulatory framework around platforms epitomizes light-touch regulation. Like the few global banks that had dominated financial services before the Great Recession, there are a few global tech giants that dominate platforms, but how they operate is opaque. And they are exhibiting bad behaviour more and more frequently through a tangled web of connections so complicated that it would take a machine learning algorithm to figure them out. More insidious is the surveillance capitalism operating via the advertising-driven business model of many of the platforms. Further, there are concerns shared around the globe, regardless of individual societies’ different values, about how information is being used, from issues of privacy to monetization.

Fuelled by light-touch regulation, and in no small measure by hubris, banks grew in size and power, leading to some exceptionally large global banks.

Indeed, the potential negative impact of the misuse of information collected by the platforms would make the negative impact of the global financial crisis pale in comparison, given how technologies permeate every aspect of our lives and will continue to do so, both at an increasing pace and in ways we cannot even envisage right now. Indeed, the Internet of Things, 5G and digital identities embody systemic risk, through their interconnectedness. And the risks are profound: from cyber warfare to state surveillance and privacy invasion, to data breaches and large economic and personal income losses and, ultimately, a loss in trust. And there is an East-West geopolitical divide as the United States and China compete head-to-head for supremacy in the data and AI realm with others caught in the middle.

Yet, the potential for these technologies to improve the everyday lives of people is substantial and derives in part through the interconnectedness that is based on trust. In fact, the greatest benefits arise when all can participate in one global internet economy rather than in a digital economy splintered into different realms.

The time to act — globally — is now: to develop a governance framework, globally, and to ensure that these technologies are used for the greater good, globally.

A Model and a Way Forward

One way forward is to draw from the lessons of the financial crisis and how policy makers dealt with the large economic and financial issues that resulted. In particular, in the heart of the crisis, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) was created (from the existing Financial Stability Forum) and given a mandate by the G20 to promote the reform of international financial regulation and supervision, with a role in standard setting and promoting members’ implementation of international standards.

Some background about the functioning of the FSB will help to set the stage. The main decision-making body is the plenary, which consists of representatives of all members: 59 representatives from 25 jurisdictions; six representatives from four international financial institutions; and eight representatives from six international standard-setting, regulatory, supervisory and central bank bodies. In carrying out its work the FSB promotes global financial stability by “coordinating the development of regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies and conducts outreach to non-member countries. It achieves cooperation and consistency through a three-stage process.”1 The three-stage process consists of a vulnerabilities assessment, policy development and implementation monitoring. Each area has several working groups that comprise not only individuals from member countries and international standard-setting bodies, but also from non-member countries and organizations that may also be affected.

One of the first steps of the new institution would be to document all of the current activities — looking for commonalities and key areas of divergence, gaps and institutions involved.

Reforming international financial regulation and supervision was a daunting task — indeed, it’s work that continues to this day — given that mandates and cultures vary tremendously across the institutions involved in regulating and delivering financial services — central banks, private banks, capital markets, securities and insurance regulators, standard setters, policy makers and so on. And reform efforts met with tremendous resistance, including complaints about rising regulatory burdens and costs. Ultimately, however, it was clear that regulation had been too lax and urgently needed to be addressed.

The FSB’s innovative multi-stakeholder processes have been essential to carrying out its responsibilities. Despite the daunting task that the FSB faced, the significant progress in financial sector reform is proof that these processes can achieve real and substantive reforms. These processes provide a model that might be useful for platform governance, but how we do go about adapting them?

Create a Digital Stability Board

A way forward is to create a new institution — let’s call it the Digital Stability Board (DSB) — and give it a mandate by global leaders. A plenary body would set objectives and oversee work of the DSB and consist of officials from countries who initially join the organization. In addition, the DSB would work with standard- setting bodies, governments and policy makers, regulators, civil society and the platforms themselves via a set of working groups with clear mandates that would report back to the plenary. For example, the broad objectives for the DSB could be to:

- Coordinate the development of standards, regulations and policies across the many realms that platforms touch. The areas would include — but not be limited to — governance along the data and AI value chain (including areas such as privacy, ethics, data quality and portability, algorithmic accountability, etc.); social media content; competition policy; and electoral integrity. The objective of coordination would be to develop a set of principles and standards that could be applied globally while allowing for domestic variation to reflect national values and customs.

- Monitor development, advise on best practices, and consider regulatory and policy actions needed to address vulnerabilities in a timely manner.

- Assess vulnerabilities arising from these technologies, including their impact on civil society and the regulatory and policy actions needed to address them on a timely basis.

- Ensure that this work feeds into other organizations such as the World Trade Organization, which needs to modernize trade rules to reflect big data and AI, but also to develop a framework with which to assess the implications for trade and trade rule compliance.

The goal is not to reinvent work already in progress. There are many notable and substantive initiatives across the globe that could be drawn into the DSB, but they are generally not coordinated and, in many cases, have narrow mandates that may not be representative of wider interests. The goal is to coordinate these efforts and fill in gaps as required. The following are some initiatives already begun.

Standard Setting

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) has launched the Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems (IEEE Global Initiative). The International Telecommunication Union has its Global Symposium for Regulators. Domestic equivalents would also be drawn in as required. The International Organization for Standardization and the International Electrotechnical Commission have begun standards development activities under the aegis of the Joint Technical Committee (JTC 1). The FSB itself is examining the implications of fintech and how it may require an update of regulatory rules and standards.

Big Data and AI Governance

The OECD has recently released its AI Principles;2 the European Union has enacted the General Data Protection Regulations related to privacy and has several other initiatives in motion; the United Nations, through its High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation, has just released its report calling for the UN Secretary-General to facilitate an agile and open consultation process to develop updated mechanisms for global digital cooperation (UN 2019). Canada, along with eight other countries, participates in the Digital 9 group, in which participants share world-class digital practices, collaborate to solve common problems, identify improvements to digital services, and support and champion growing digital economies.3

Policy

The UK government has outlined many initiatives, including its Online Harms Paper (HM Government 2019), as well as Unlocking digital competition: Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel (HM Treasury 2019). Canada has released its national intellectual property strategy4 and cyber strategy (Canada 2018), and recently announced its Digital Charter.5

Democracy

Many significant efforts exist in this area, including reports from the European Commission High Level Expert Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation (2018), the UK Parliament’s Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee on disinformation and fake news (UK House of Commons 2019), the Knight Commission on Trust, Media and Democracy (2019), the LSE Truth, Trust & Technology Commission (London School of Economics and Political Science 2019), and the French Government’s Créer un cadre français de responsabilisation des réseaux sociaux: agir en France avec une ambition européenne (Potier and Arbiteboul 2019).

The platforms have also announced initiatives: Google (2019) has recently released its proposal “Giving users more transparency, choice and control over how their data is used in digital advertising,” Apple and Microsoft have called for stronger privacy laws, and Facebook is in the process of developing its content review board (Bloomberg 2018; Microsoft 2019; Harris 2019).

Why a New Institution?

To give this important governance framework initiative any hope of succeeding requires the formation of a new institution — the DSB. The current Bretton Woods institutions have their hands full and do not have the expertise in all of these areas. Allowing them to formulate the reforms would likely leave the process piecemeal — its current state. As with the undertaking of financial regulatory reform, undertaking reform in the digital sphere requires creating this new institution and would also both signal and acknowledge the importance of setting global standards and policies for big data, AI and the platforms. The stage is already set to move forward with an organization like the DSB. Recognizing the key role that data now plays in the global economy, as well as the importance of trust to underpin the uses of data, the current Japanese G20 presidency has “data free flows with trust” as one of its key themes.6

The International Grand Committee on Big Data, Privacy and Democracy — which comprises a diverse set of 11 countries and more than 400 million citizens — could serve as a natural springboard to launch the DSB. The Committee’s focus has been on the behaviour of platforms, including their role in disseminating fake news. The diversity of the membership — small and large countries, with differing cultures, values and institutions — makes it ideal for launching the DSB. Funding would come from its member countries alongside voluntary donations and in-kind contributions via participation in the DSB working groups.

This year is the seventy-fifth anniversary of Bretton Woods. Announcing the formation of this institution would recognize the important role that the Bretton Woods institutions have played in promoting a rules-based system — which has led to vast improvements in living standards — while also recognizing the need to update these arrangements to reflect the profound implications arising from digital platforms.

One of the new institution’s first steps would be to document all of the current activities — looking for commonalities and key areas of divergence, gaps and institutions involved. Eventually, it would develop a universal declaration on AI ethics, patterned on the universal declaration on human rights. These will require substantive work and are worthy goals for a new institution to undertake.

It Is a Beginning, Not an End

The DSB is a starting point. It is likely that a diverse set of countries and stakeholders would want to take part, and in fact would be necessary for the organization to have legitimacy.

It is also likely that there will be resistance to new forms of regulation and ways of doing business in the technology platform space, just as the creation of the FSB drew opposition. But as with financial sector reform, these efforts are essential to achieve the full benefits from the platforms. They will build and solidify trust, and trust is ultimately what will attract users to a platform. In keeping with the open nature of the World Wide Web, the process for reform should be open to all countries and organizations that wish to join, either at the outset or as the reform process matures.

And the time to start is now.