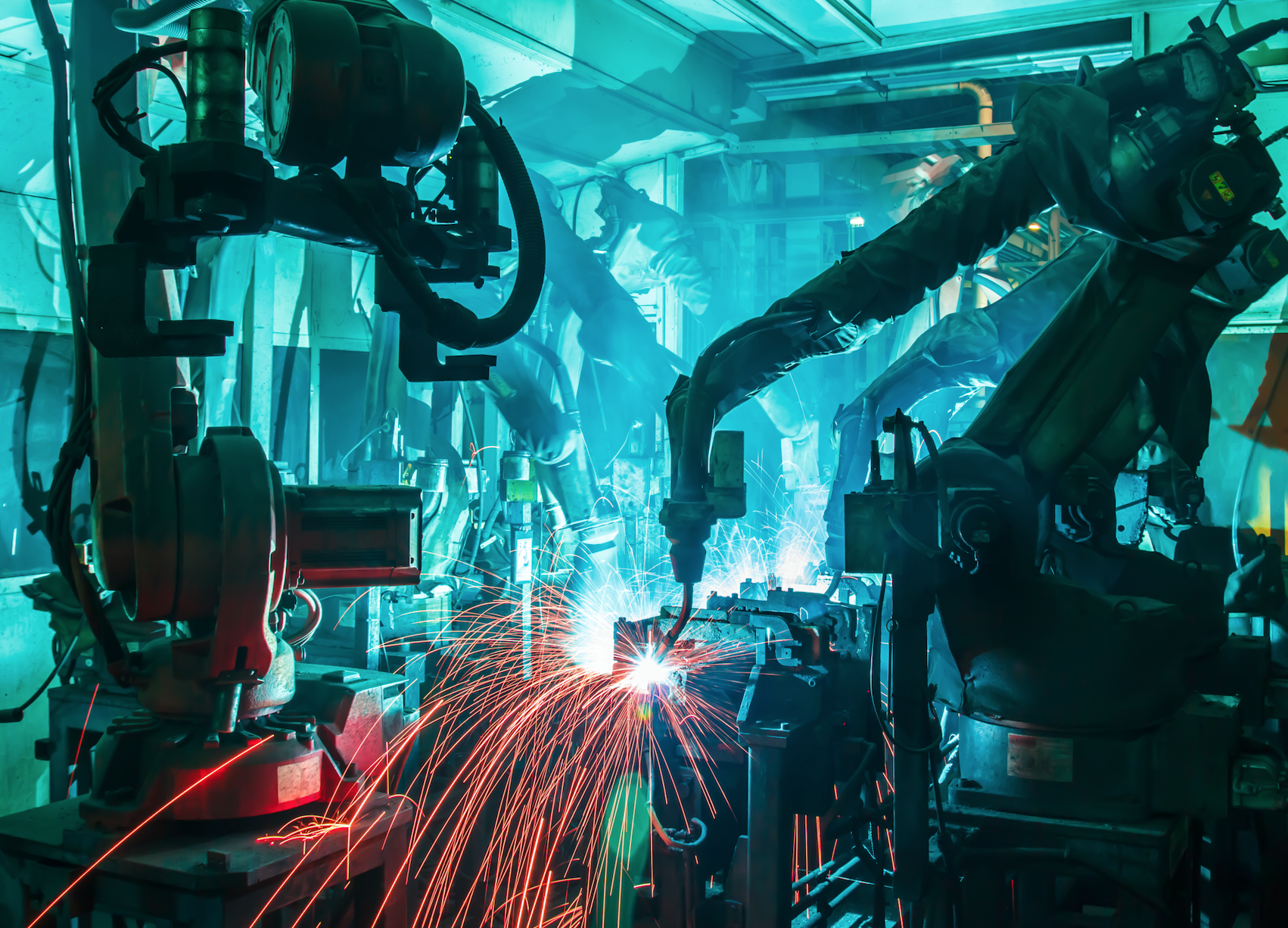

The fourth industrial revolution is well under way, with us adopting new technologies such as virtual reality, artificial intelligence, robotics and 3-D printing.

At the root of these new and disruptive technologies is intellectual property (IP), and it has been said that it is the driving force behind this revolution. We are witnessing a surge of new technologies and an aggressive pursuit for global dominance through IP ownership. This is a new kind of arms race – it is an economic race to the top, and if we in Canada don’t step up our IP game, we risk being left behind.

Countries that will enjoy the greatest economic benefit are those that have IP rights in relation to these powerful technologies. IP rights offer exclusive control over these new technologies – the right to refuse to grant permission for others to gain access, or to extract revenue from licensing.

In this Darwinian context, those that own IP rights can be disruptors while those that don’t will be disrupted. In practical terms this means that for Canadian businesses to thrive, or perhaps even survive, they must aggressively protect the IP related to these technologies and learn how to strategically leverage these protections for commercial advantage.

But, in order to do this, businesses must first develop a profound understanding of IP rights themselves and the ways in which they can be strategically deployed. Canadian IP-intensive companies have to have sophisticated levels of IP literacy. Unfortunately, our current IP education system does not foster that kind of literacy.

For the most part, IP knowledge in this country is largely taught in law schools. This means that Canadian innovators have to rely on lawyers to help them navigate the IP landscape. This poses a number of challenges.

First of all, legal advice is expensive and is often not affordable for many innovators. Second, because most innovators don’t even understand the basics about IP, they are typically not well equipped to have a meaningful conversation about IP with their lawyers. While most Canadian law schools offer courses on IP law, very few of them teach law students about the strategic uses of IP.

So what does this all mean? We need to make more of an effort to improve IP education in Canada.

There needs to be a dramatic shift and time is not on our side. While, training lawyers in IP is essential, lawyers are not the most important recipients of this knowledge. IP education needs to pervade the entire innovation ecosystem, and it must focus especially on expanding the IP knowledge and skills of Canadian innovators.

Specifically, IP education has to extend outside of the law school setting. Raising the levels of IP awareness should start within the school setting but at the very least should extend into every discipline within the postsecondary setting.

It’s equally important for our designers to understand how industrial design protection might give them a competitive advantage in a global marketplace where 3-D printing is pervasive, as it is for our engineers to understand how to use expired patents for intelligence-gathering purposes. It’s also vital for our business leaders to understand how IP can factor into their business strategies.

For example, they need to appreciate how a strong patent portfolio can be used to deter predatory practices or how an IP portfolio that consists of multiple forms of IP (not merely patents) can be used as part of a licensing program to generate high profit margins.

Specifically within the law school setting, it is important to teach law students more than the basics of IP law. Because IP rights are increasingly becoming vital strategic tools for economic growth, the next generation of IP lawyers will have to become expert IP strategists in order to counsel their clients on integrating IP into their business strategies. The law school curriculum must reflect this new landscape.

Canadians are leaders in innovation research and we rank very high in levels of postsecondary education. However, if we want to continue to prosper as a country, we must take swift and decisive action to improve levels of IP literacy across the board. We need to grasp the reality that IP is increasingly being deployed as a strategic tool for businesses and countries alike, and we need to be fully prepared to meet the challenges of this new IP revolution head on.

Karima Bawa participated in the Canada Future Forward Summit, held by The Globe and Mail in partnership with McKinsey and CIGI.

This article originally appeared in The Globe and Mail.