The United States and Canada have been remarkably slow to recognize the potential geopolitical consequences of a warming Arctic at a time that may be a tipping point in the global balance of power.

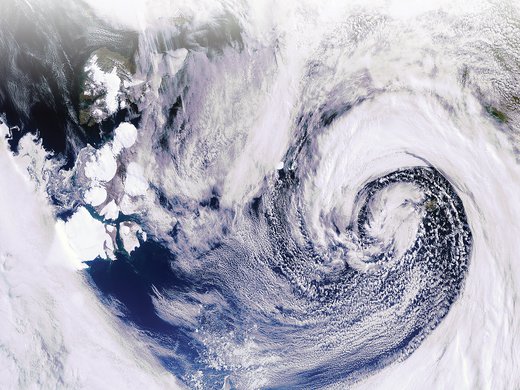

In coming decades, the melting ice cap will make the Arctic’s abundant resources more accessible, disputed maritime boundaries more volatile, surface naval probes and conflict less likely, new marine corridors more economically viable, growing fisheries more attractive to pirates, and communities and ecosystems more vulnerable.

The international governance framework, including the Arctic Council now chaired by United States, reflects the peaceful and optimistic world of the early 1990s when Russia and China were weak and “well behaved.” But current Arctic multilateral cooperation is thin, fragile and prone to wishful thinking, when viewed from Moscow and Beijing.

Russia, with new backing by China, is moving into the Arctic vacuum as part of an emerging global “hard power” partnership to expand territorial, political and cyber realms.

Surprises abound. Russia expands into Ukraine and now Syria, probing NATO’s soft spots, as China builds maritime forts in the South China Sea, steadily increasing the quality of its military and cyber power.

Russia has officially declared China its preferred partner in the Arctic, reacting against Western sanctions. Overlooked by the media, Arctic cooperation between Russia and China has dramatically intensified in recent months, signalled by exchanges of leaders’ visits with a military flavour, a plethora of both “commercial” and government to government agreements, and military cooperation above and below the radar.

The Arctic is just one area where Russian and Chinese economic and global political interests converge, signalling at best a temporary alliance (China has money, Russia needs it), at worst a logical partnership between complementary economies under autocratic regimes with common expansionist and revanchists goals. The difference from their alliance in the 1950s is that China is now the “big brother,” and the West is weak and divided.

China’s Arctic interests can prosper on a strong Russian Arctic base. President Vladimir Putin sees the great Arctic melt as an opportunity, not a problem. It fits his domestic nationalist agenda and promises a road back to lost Soviet greatness for Russia’s huge landlocked empire.

The Russian Federation, with its growing fleet of powerful icebreakers, the Northern Sea Route Administration, and massive oil and gas and port and rail facilities, has been pushing Arctic economic development full speed ahead for decades, largely paying lip service to other goals. Low oil prices and half-hearted Western sanctions will slow for a time but not stop Arctic oil, gas and mining state-driven activity in Russia.

Meanwhile, American and Canadian Arctic policy is largely animated by domestic politics and a curious myopia about Arctic change.

Despite US President Barack Obama’s unprecedented Arctic adventure in Alaska and Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s yearly Gaullist “show the flag” visits to the North to deter largely imagined threats to Canada’s Arctic “sovereignty,” neither country is in the race for a lead role in the new, opening and, potentially, contentious Arctic Ocean.

Canada is winding up a federal election campaign and the Arctic has not even been an election issue, although Arctic identity politics are a familiar tool in Canadian politics.

Why? There are few people or votes in Canada’s vast Territories, big Arctic marine and security ideas and infrastructure are expensive, and the government’s Arctic policy is modest but adequate — unless viewed through a larger global lens.

As Liberal leader Justin Trudeau said in a debate about Harper’s Arctic policy: “Big sled, no dogs,” while offering no “dogs” himself.

The Obama administration deserves considerable credit for trying to develop a new Arctic strategy and working to implement it over the last three years. Agencies have produced a small mountain of impressive studies, and there are signs of greater focus and a deeper awareness of Alaskan interests.

However, toxic relations between the Obama administration and Congress mean no cheques are in the mail for the maritime and surface transport, energy infrastructure, focused science, Coast Guard icebreaker and Navy projects, and Alaskan community support, the areas of focus pointed to in the studies.

President Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry’s lament for melting glaciers and wave erosion in Alaska at the GLACIER summit was no doubt welcomed by US Democrats and environmental absolutists in their “civil war” with Republicans over climate change.

Unfortunately, it was a single issue summit that lost an opportunity for wider national and international leadership based on the president’s Arctic strategy.

There is no evidence that the GLACIER summit moved the needle on international action on climate change, and it ignored a wide range of pressing national and bilateral Arctic issues as defined by Alaska’s excellent legislative review of Arctic policy.

Twenty foreign ministers were invited to GLACIER, but only a few smaller Arctic countries’ foreign ministers came. None of the cool kids — for example, Russia, China, India and other Group of Eight countries — sent high-level political representatives.

The program offered no public forum for ministers and others who did come. Some felt they were invited merely as props for Obama’s speech. A diplomat from a very important power drily said, “Our level of representation reflected our view of the significance of the meeting.”

Some Arctic countries came with a fear that this larger gathering would set a precedent for a larger Arctic grouping, an “A20” that would dilute the power of regional states and aboriginals at the Arctic Council table and enhance that of observers, who have legitimate interests not fully reflected in the council.

While Alaskans were genuinely flattered that Obama came up on an unprecedented full presidential visit, it was not because of his climate change theme. They hoped for greater sensitivity to the special problems and opportunities of a resource-based state that borders Russia as the Arctic Ocean melts.

Before the visit, most Alaskan officials were furious at the administration for further restricting oil and gas development as Alaska faces bankruptcy in a few years because of aging Prudhoe Bay exports and the drop in the price of oil.

Then, Shell stunned Alaskans and other prospective North American Arctic energy producers by pulling the plug on its massive offshore oil and gas exploration project.

While global oil market conditions were the main reason for this decision, the president’s GLACIER message probably helped pushed Shell over the edge, citing continued regulatory uncertainty (read: continued active administration hostility) as an important factor. The next US election offers little or no chance of reversing this verdict.

Viewed from a global perspective, North America is losing the great game in the Arctic. Worse, few are even aware that a battle is taking place.

Peaceful multilateral Arctic cooperation remains an important diplomatic objective for the United States and Canada, including keeping channels of cooperation open with Russia. But bold, purposeful Canadian, US and NATO moves to forestall eventual Russian Arctic maritime and political hegemony with China’s financial and technical support, are now urgently required.