Episode Description

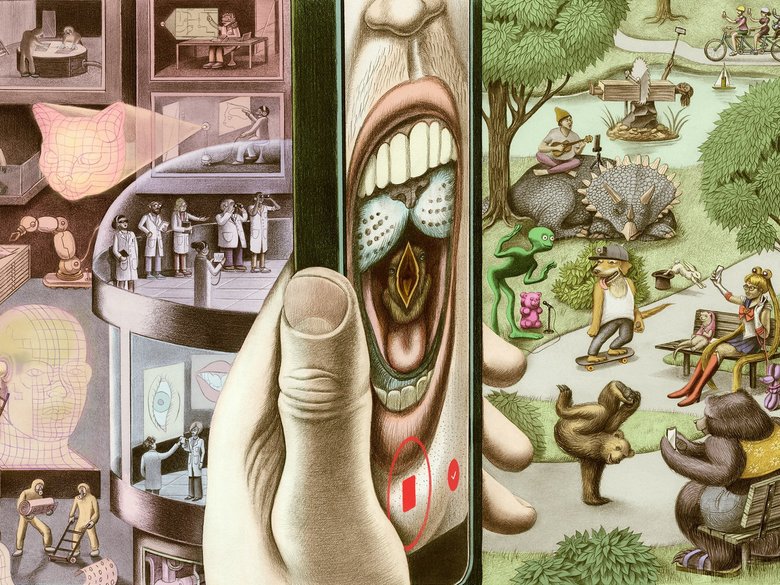

In this episode, the Policy Prompt hosts are joined by Grant Bollmer and Katherine Guinness, authors of The Influencer Factory: A Marxist Theory of Corporate Personhood on YouTube (Stanford University Press, 2024), to discuss the evolving landscape of influencer culture. The episode touches on the growing phenomenon of “uncancelability” among influencers, the rise of artificial intelligence–powered avatars and the impact of fluctuating platform regulations.

Mentioned:

- The Influencer Factory: A Marxist Theory of Corporate Personhood on YouTube (Stanford University Press, 2024)

- The Influencer Marketing Hub claims that the worldwide influencer marketing industry is worth nearly US$21.1 billion, a 29 percent jump from 2022

- Jon Porter, “TikTok’s big day in court is here: all the news on attempts to ban the video platform” (The Verge, September 16, 2024)

- AI Influencer profile, Miquela “Lil Miquela” Sousa: Miquela (@lilmiquela) Instagram photos and videos; Eric Chang, “@LilMiquela is an Instagram IT Girl, Social Influencer, and Recording Artist — She’s Also a Digital Simulation” (Vogue, August 17, 2017)

In-Show Clips:

- Mia Maples: “Testing Tiktok VIRAL Products”

- A Beautiful Mess: “Elsie’s Home Tour Video”

- MrBeast: “Train Vs Giant Pit”

- StarTalk: “William Shatner Has Questions for Neil deGrasse Tyson”

- BeFullyDevoted: “THE DAILY GRACE CO HAUL”

- Shane Dawson: “The Secret World of Jeffree Starr”

- The Try Guys: “the new try guys”

- Lil Miquela: Miquela (@lilmiquela) Instagram photos and videos

Further Reading:

- Grant Bollmer’s official website

- Katherine Guinness’s official website

- Grant Bollmer’s Materialist Media Theory: An Introduction (Bloomsbury, 2019)

- Grant Bollmer’s Theorizing Digital Cultures (Sage, 2018)

- Contemporary Absurdities, Existential Crises, and Visual Art, edited by Katherine Guinness and Charlotte Kent (Intellectual Books, forthcoming October 2024)

Credits:

Policy Prompt is produced by Vass Bednar and Paul Samson. Our technical producers are Tim Lewis and Melanie DeBonte. Fact-checking and background research provided by Reanne Cayenne. Marketing by Kahlan Thomson. Brand design by Abhilasha Dewan and creative direction by Som Tsoi.

Original music by Joshua Snethlage.

Sound mix and mastering by François Goudreault.

Special thanks to creative consultant Ken Ogasawara.

Be sure to follow us on social media.

- X: @_policyprompt

- IG: @_policyprompt

Listen to new episodes of Policy Prompt biweekly on major podcast platforms. Questions, comments or suggestions? Reach out to CIGI’s Policy Prompt team at [email protected].