Unleashing the Nuclear Watchdog: Strengthening and Reform of the IAEA

Overview

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is the principal multilateral organization mandated by the international community to deal with nuclear issues. Established in 1957 and based in Vienna, it is essentially the nucleus around which all other parts of the global nuclear governance system revolve.

Viewed as one of the most effective and efficient organizations in the UN family, the IAEA has, in many respects, evolved deftly — shedding unrealizable visions, seizing new opportunities and handling with aplomb several international crises.

After 55 years, while the IAEA does not need a dramatic overhaul, it could benefit from strengthening and reform.

Nuclear Safety

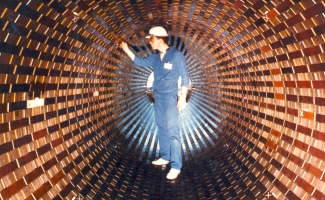

The Agency’s involvement in the safety of nuclear facilities and materials derives from international treaty obligations, as well as from a gradual accretion of responsibilities and functions.

A large part of the IAEA’s role is establishing and promoting safety standards with respect to nuclear reactors and materials — including nuclear waste and spent fuel. The IAEA also has an impressive array of safety-related programs to help states improve nuclear safety, including:

- providing assistance

- fostering information exchange

- promoting education and training

- coordinating research

- coordinating development

- rendering services

On the surface, the IAEA’s role has grown and the Agency is increasingly seen as a central actor. Yet, the system is fragmented, with too many plans and programs for even the most attentive of member states to understand or participate in. Some states are skeptical about an intrusive IAEA role in nuclear safety. Such states, along with the nuclear industry, have consistently argued that the only role the international regime should have is in recommending, facilitating and assisting in this critical area.

Nuclear Security

The nuclear industry is affected by security in a way that other forms of energy generation are not. This is partly a legacy of the highly secretive nuclear weapons programs from which civilian applications emerged and due to the strategic nature of the facilities and materials involved.

While nuclear security has had a higher profile in IAEA activities since 9/11, the Agency still operates with cautiousness due to member state sensitivities and because other international processes are at play, such as the Nuclear Security Summit initiated by the US in 2010. The global governance regime for nuclear security also offers the challenge of being more fragmented than (and not nearly as Agency-oriented as) the well-established regime for nuclear safety.

Still, the IAEA plays a crucial role in helping to implement the existing legal instruments concerning nuclear security.

Nuclear Safeguards

The IAEA’s nuclear safeguards and verification system, while a constant work in progress, is a major achievement of international governance, imposing a degree of intrusiveness on states that is unknown in almost any other field.

Safeguards Objectives:

- provide warning of diversion from peaceful uses to weapon purposes;

- deter potential non-compliers with costly penalties; and

- help all parties demonstrate non-proliferation undertakings.

Opponent concerns:

- impingement on state sovereignty;

- intrusiveness on state security and commercial confidentiality; and

- relative cost and prominence within IAEA’s overall mandate.

Since the entry into force of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (1970), the IAEA has continued to strengthen its safeguards system. In May 1997, the IAEA Board of Governors agreed on the Model Additional Protocol (AP), which expanded the verification responsibilities of both the Agency and each state party.

IAEA Management

Despite the highly political atmosphere in which it often operates, the IAEA Secretariat has largely retained its reputation as an objective, impartial and professional body that is well managed and administered, especially compared to the UN norm. Nonetheless, there are accusations from certain member states that it is: not cost-effective enough; insufficiently transparent; not driven by results-based management; lacking in metrics of success; and inadequate in its planning and financial processes.

Organizationally and managerially, the IAEA is hobbled by long-standing constraints. Structural divides and concentrated authority have led to unhealthy competition between departments and a divergence from the “one house” ideal.

The Agency also lacks a proper strategic plan, using instead the Medium-Term Strategy, the latest of which covers the years 2012–2017 and is essentially a list of all the activities that the Agency currently carries out, without prioritization.

The IAEA also suffers from generational change with 22% of its inspectors due to retire and the Secretariat, as a whole, is facing bloc retirements. Further, ongoing competition from industry and national regulatory bodies — combined with the lack of an agile staff recruitment and retention policy — make it difficult for the Agency to offer salaries and benefits that can attract top talent.

Conclusions

The role the IAEA plays in international peace and security, considering its capabilities, size and budget, makes it an indisputable bargain. However, the Agency must prepare for potential future challenges:

- The Agency’s safeguards and other verification capacities will need ongoing enhancement, especially for detecting undeclared activities.

- The Agency’s roles in nuclear safety and security will, by their very nature, always be works-in-progress.

- New special verification mandates may arise or be resurrected at any time, as in the cases of Iran, North Korea and Syria.

- The Agency is likely to be offered a role in verifying steps towards global nuclear disarmament, beginning with a Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty and assistance with bilateral US/Russia cuts.

- Despite Fukushima, runaway climate change may induce rapid demand for nuclear electricity and a deluge of requests for the Agency’s advisory and assistance services.

As an impartial facilitator and, in some cases, active driver of treaty implementation, the Agency plays a part that even the most powerful of states could not manage alone.

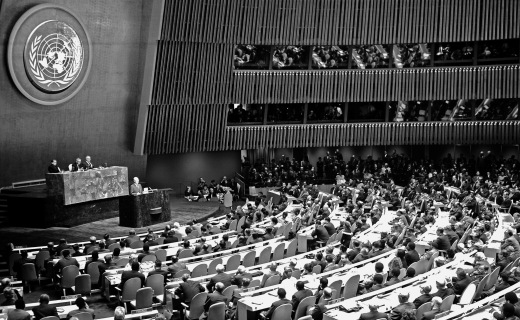

Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace speech at UN General Assembly

1953

Seeking a way out of the growing nuclear arms race, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower proposed an “International Atomic Energy Agency” to the UN General Assembly that would facilitate the spread of peaceful nuclear technology.

Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” speech in December 1953 was widely perceived as a master stroke of US diplomacy.

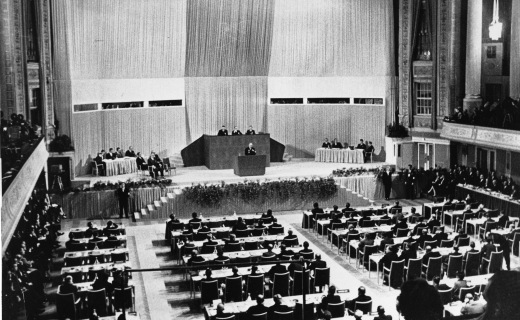

First IAEA General Conference

1957

The first IAEA General Conference approved Vienna as the seat of the organization, recommended that priority be given to nuclear activities of benefit to developing countries, and approved the appointment of an American, Sterling Cole, as the first Director General.

The founding years saw peaceful uses of nuclear energy heavily promoted while the Agency also began providing technical assistance in such areas as agriculture and medicine.

At the same time, the IAEA struggled to make its mark, as some of its anticipated functions either disappeared or were purloined by others. For example, the envisaged IAEA stockpile of nuclear material never materialized.

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty concluded and enters into force

The arrival of the NPT gave the IAEA the task of verifying compliance by the non- nuclear weapon states (NNWS) with their non-proliferation obligations, but it also introduced enduring structural complications for the agency.

The treaty affirmed that in return for assistance in the peaceful uses of nuclear technology the NNWS would not seek to acquire nuclear weapons. Existing nuclear weapon states were also prohibited from assisting any NNWS to acquire nuclear weapons.

Most critically of all, it called for “negotiations in good faith” by all NPT parties to achieve nuclear disarmament.

Today the NPT is almost universal, with one withdrawal (North Korea) and three significant remaining “holdouts”: India, Israel and Pakistan.

India’s “peaceful nuclear explosion”

(Smiling Buddha/Pokhran-I)

1974

The detonation of a nuclear device in May 1974 by India, a non-party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), was an unexpected shock.

Although India had only violated a “gentleman’s agreement with Canada and the United States,” the test spotlighted the “peaceful nuclear explosion” loophole in early safeguards.

The Indian explosion also led to the establishment of the Nuclear Suppliers Group that seeks to agree to guidelines that restrict the export of certain nuclear and dual-use materials, equipment and technologies.

In 1979, the IAEA Board of Governors approved a revised version of the Guiding Principles and General Operating Rules for the provision of Technical Cooperation, which sought to avoid the misuse of Technical Cooperation for so-called peaceful nuclear explosions.

Chernobyl Disaster

1986

The 1986 Chernobyl disaster was a wake-up call to the nuclear industry, national governments and the international community: global nuclear safety requires a global approach.

The disaster paradoxically revived the IAEA’s fortunes in the area of nuclear safety, spawning the 1986 Convention on Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident and the 1986 Convention on Assistance in the Case of a Nuclear Accident or Radiological Emergency.

After Chernobyl, numerous other initiatives were taken to strengthen the global governance of nuclear safety.

Iraq Nuclear Inspections

1991-2003

The general complacency over safeguards was shattered with the revelation after the 1990 Gulf War that Iraq had been clandestinely mounting a nuclear weapons program in parallel with its IAEA-inspected peaceful program.

The IAEA’s failure to detect Iraqi activities, located in some cases “just over the berm” from where inspectors regularly visited, brought ridicule from those who misunderstood the limitations of the Agency’s mandate and despair on the part of safeguards experts who had for years feared this outcome.

After the discovery that Iraq had come close to nuclear weapons capability, the IAEA strengthened its verification system, not least through adoption of the Model Additional Protocol.

In 2003, the IAEA and its Director General found themselves at the heart of an international crisis as the UN Security Council considered whether to authorize a military operation against Iraq on the grounds that it had not removed its so-called weapons of mass destruction capabilities.

North Korea non-compliance crisis

1992 - present

In 1992, North Korea was found in non-compliance of its safeguard agreements, and left the NPT and the IAEA in 1994. The Six-Party Talks were designed to bring North Korea back into compliance but they floundered when it was revealed that North Korea had a uranium enrichment program in addition to its previously discovered plutonium program.

The so-called Leap Day Deal between North Korea and the United States in 2012 was the first hopeful sign in years that IAEA inspectors may be invited back, this time to verify a halt to uranium enrichment. Since then, prospects have dimmed after another missile test by North Korea which was in violation of UN Security Council resolutions — North Korea had previously detonated two nuclear devices, one in 2006 and one in 2009.

If and when the Agency re-engages with North Korea, it will need to develop credible and sustainable means of verifying a uranium enrichment freeze, in addition to re-instituting its past activities with respect to plutonium production and, ultimately, de-weaponization.

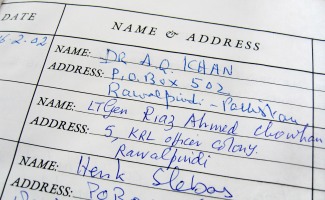

A.Q. Khan network revealed

1993

The IAEA began probing illicit nuclear smuggling activities through the discovery of network operated by Pakistani nuclear program director Abdul Qadeer (A.Q.) Khan.

Through his training at the URENCO enrichment plant in the Netherlands and with stolen blueprints, Khan spearheaded an enrichment program in Pakistan, which led to the country’s acquisition of nuclear weapons.

Khan subsequently set up an international smuggling network to provide Iran, Libya and North Korea with various degrees of illicit nuclear assistance, including blueprints for Iran’s enrichment program.

The IAEA’s activities in countering nuclear smuggling are intended to further both nuclear security and non-proliferation objectives. Since the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the IAEA also plays a role in preventing nuclear terrorism.

The Convention on Nuclear Safety

1994

The Chernobyl nuclear accident (1986) provided the impetus for the 1994 Convention on Nuclear Safety (CNS)—the first legally binding multilateral nuclear safety treaty—and the 1997 Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management.

Applying to land-based civilian nuclear power reactors and their radioactive wastes and spend fuels, the CNS requires its contracting parties to submit detailed, periodic national reports for peer review.

While the IAEA’s formal duties in implementing the CNS are restricted, in practice the Agency has a significant degree of influence on the treaty’s operation: organizing the peer review system, promoting nuclear safety, assisting states in achieving it and promulgating influential standards and guides.

Iran nuclear controversy

2003-present

Since 2003, the IAEA has been embroiled in a continuing struggle with Iran in order to determine the precise details of the country’s non-compliance with its safeguards agreement.

Although taxing on the IAEA Secretariat, the Iran case has enabled the Agency to demonstrate the power of strengthened safeguards, notably those that do not require Iran to adopt an Additional Protocol.

Ultimately, the standoff with Iran is a failure of the mechanisms meant for dealing with non-compliance and the case has soured the atmosphere in the IAEA Board of Governors, deterring it from taking additional safeguards-strengthening measures.

Syrian non-compliance and Israeli attack on reactor

2007

In September 2007, Israel attacked a facility in Dair Alzour, Syria that was believed to be the site of a nuclear reactor built with North Korean assistance. The IAEA called on Syria to provide further information but Syria offered little cooperation and maintained that the destroyed facility was not nuclear related.

Eventually Syria agreed to an IAEA visit to the location in June 2008 where evidence gathered indicated that the destroyed facility was “very likely” a nuclear reactor.

Other potential nuclear sites have been identified in Syria. No enforcement action has been taken to date by the UN Security Council on this issue.

Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster

2011

Following the events at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi reactors on March 11, 2011, the IAEA’s halting response led many observers to question its effectiveness as the global “hub” of nuclear safety.

Several international gatherings thereafter have urged the IAEA to improve its preparedness for nuclear accidents and emergencies.

A Draft Action Plan on Nuclear Safety, agreed to in September 2011 by the general conference and board of governors, contains a long-list of initiatives to be taken by member states, the Secretariat, and other stakeholders, but does not commit anyone to mandatory steps. Notably, the Action Plan does not commit states to mandatory IAEA-led nuclear safety peer reviews.