This transcript was completed with the aid of computer voice recognition software. If you notice an error in this transcript, please let us know by contacting us here.

[CLIP]

Mark Zuckerberg: But at some level, I do think that we don't want private companies making so many decisions about how to balance social equities without a more democratic process. So I think that where the lines, in my opinion, should be drawn is there should be more guidance and regulation from the States, basically, on what kind of take political advertising, as an example. What discourse should be allowed?

SOURCE: Munich Security Conference

Learn Fast and Fix Things: Social Media and Democracy

February 15, 2020

Munich, Germany

[CLIP]

Maria Tadeo: I want to talk about Mark Zuckerberg because he was here on Monday and he seemed to be saying, "You know what, I'm happy to see more guidance from governments and I'm happy to do regulation". Some will tell you it's a big shift in tone. I'm not sure if I buy it.

Margrethe Vestager: Well, there's a difference between a shift in tone and then a shift in behaviour, of course. And I think everyone appreciate that we can have other debates by now about the responsibility of giant the platforms. But I think the important thing is to see real change on ground and in that, well, we are still considering if not a regulation is needed to make sure that all the things that we have discussed and decided in the real world also in is represented when we're in our digital reality.

SOURCE: Bloomberg Technology YouTube Channel

EU's Vestager on Regulating Big Tech and Digital Citizen Rights

February 19, 2020

Brussels, Belgium

[MUSIC]

David Skok: Hello and welcome to Big Tech, a podcast about the emerging technologies that are reshaping democracy, the economy and society. I'm David Skok.

Taylor Owen: I'm Taylor Owen.

David Skok: We're breaking into our regular broadcast schedule, Taylor, because it's been a big week for tech policy nerds, like us, in Europe. Just in the last week, Facebook CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, dropped in on the EU parliament to pitch his proposal for how he should be regulated.

Taylor Owen: And on Wednesday, the EU unveiled its long-awaited strategy for taking on US tech, as well as proposals for regulating AI and a whole new competition policy regime.

David Skok: So, Taylor, why should what's happening in Europe matter for the rest of us?

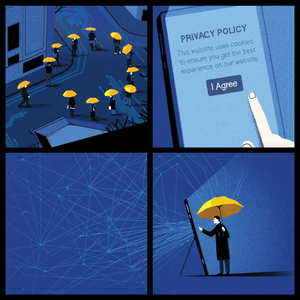

Taylor Owen: Well, it really does. The internet is splintering into different global blocks. The Chinese government has a real state centric view of top down control of the internet. The United States has a much more free market view that's Firm-Centric and Company-Centric, but the EU has a focus on rights and on the rights of their citizens, and how to protect them through regulations, and how to enable an industrial space around AI and around social media companies. That puts the individual rights at the centre of them. So how Europe chooses to govern the internet could really affect us all.

David Skok: All right. To find out about what happened this week, we spoke with Mark Scott, the chief technology correspondent at POLITICO. Mark was in Brussels to cover the trip and we connected with him in his London office right before he was filing his latest story. Mark, welcome to the show.

Mark Scott: Happy to be here.

David Skok: So, it's been a really busy week in the European Union and I'm wondering, when it comes to big tech, and I'm wondering if you could kind of give us a lay of the land. The EU just announced our long-awaited grand strategy for taking on the US tech companies. What was in it?

Mark Scott: Yes, so in Europe is kind of like you wait forever for digital policy to show up and then it shows up all at once. So today, on the 19th of February, the Commission, which has been planning this for quite a while, has announced the initial stages of what it wants to do with tech and digital over the next five years. It kind of divided into three areas. One is, the broad brush, what is your push on this? And the idea is to try and regain some of the landscape that is now currently dominated by the US and the Chinese players. To do that, they are breaking this down into multiple areas. One is, focusing on AI, specifically looking to create European and, hopefully, global rules about how AI and machine learning should be used by both governments and corporations going forward. This comes down to what are the ethics around facial recognition, what type of transparency tools you need for algorithms or that sort of thing. The second part is, maybe more specifically focused on helping European companies, to try and create bigger European wide pools of industrial data. So, we're not talking about people's social media feeds, all search histories. Is more to do with how big industry uses data in the everyday lives and how can we pull that together to create big data sets that then can be used to train AI and other digital services. So European companies, from many of whom have not been able to keep up so far with, say the Googles and the tenses of this world can then lead for all by accessing this region my data. So, that's what they announced today.

Taylor Owen: So, there's this then sort of a tech sovereignty play mostly then?

Mark Scott: One hundred percent. This is about trying to make sure that Europe doesn't miss out on the next wave of tech, which is frankly mostly AI. And to do that, they're looking to streamline the rules and reduce boundaries and borders between countries. Frankly, they've been trying to do this for decades. It's just the latest iteration of what the Commission, Brussels and the EU are trying to do to regain some of that power.

Taylor Owen: Is there unanimity within the EU on this? I saw some commentary about sort of some divisions coming around between Margrethe Vestager and Thierry Breton, for example, on what the purpose of this kind of strategy is. Can you talk a little bit with that?

Mark Scott: Sure. So, the weird thing about the European Union and being based here in Europe is, that nothing is as simple as it seems. There is a sense that there is a European Union, that everyone speaks from the same platform. That is not happening. There's a division right now going on with the EU between both countries and within Brussels about how aggressive Europe should be in promoting its own interests, both domestically within Europe and overseas. On in one camp you have Margrethe Vestager, who is the Europeans competition czar as well as head of the broader industrial policy. She is more focused on open markets, liberalism, allow competitors to compete and see who wins. And that's mostly from the Northern Europeans. And then Thierry Breton, who is the French commissioner, is a lot more statist interventionists, frankly Gallic, to be very stereotypical. And he is more willing to use the all the leavers that are at the EU's disposal to promote domestic, frankly national champions and companies. It is ironic that he was the former chief executive of France's former States telecom monopolies. So, you can kind of see where he's coming from.

David Skok: Mark, this came on the hills of last month, a lot of world leaders gathering in Davos for the world economic forum and taxation policy. At that moment you had obviously the French 3% tax come up and then you had Donald Trump, last shout about the tax. Was that included in part of this or is that an entirely separate conversation?

Mark Scott: So, it's part of it but not part of today's announcement. What has happened is, that amongst these the digital tax discussions that are going on within the OECD, everyone's punted it until January to 2021 to make unilateral decisions on whether to move forward. The idea of being is to give the OECD an opportunity to fix the problem. What the European Union have said they would do is, that if there's no global deal, they're going to move ahead aggressively with a European wide digital tax. Today's announcement it's part of the drum beat for regulation. Some of the Europeans are very eager to move ahead with a region wise tax. They're just holding off until December when, frankly, most people think OECD is going to fail.

Taylor Owen: Do you get the sense that there's a real feeling that this regulation will project globally? Even you hear sometimes people talk about EU plus, that this is actually not just about the European market but it's a geopolitical projection in a way.

Mark Scott: The Europeans are very eager to carry on from what they did with their privacy rules back in 2018, the idea being that if you set the de facto standard globally, others will fall in line and you can see that happening from South Korea to Brazil. This is happening within privacy. They are trying to do the same thing, when it comes to AI in particular, the concept being if we set global rules for all 500 million well-healed consumers, those who want to sell into Europe are going to have to follow those rules. And, frankly, because the US doesn't have any rules in China as a whole different thing, the rest of the world will fall in line. I'm slightly skeptical on that mostly because AI and privacy, although there is some overlap, very different areas. The Europeans have been dominating in global privacy rules since the 1990s. No one has set AI rules yet. Europe is starting from a week of base and they also don't have the domestic European champions, like the US and China do, from the corporate side to push that. So, I would be concerned about, you're trying to go global on AI rules, but, frankly, no one following them because there's no track record of Europe during that.

David Skok: Well, we want to get into the AI regulation stuff. And certainly, from a North American perspective, it is relevant, particularly in Canada, where we have some large players, like Element AI, that are also trying to step in and play that role. But before we do, have to ask about Mark Zuckerberg and his state visit to Brussels last week. What was he doing? I mean, naturally I suspect all of this stuff happening right now is causing great alarm in Menlo Park. What was he doing in Brussels and how was it received?

Mark Scott: It's funny you call it a state visit. That exactly what it was. You had to do the curtain calls, you had all the pomp and ceremony that the EU has at its disposal being rolled out. So he was in town for a couple of reasons. He was at the Munich Security Conference that we can before to talk about encryption and digital tax and sort of just show he's a good corporate citizen. Within Brussels his specific focus was on content and content liability, who should control that? What role should platforms play in policing uses material online? To be frank, it went down really badly. Zuckerberg came in with Nick Clegg, the full murder deputy UK prime minister, who's now the chief lobbyists, to sort of say, "We're the good guys, give us. You set the regulation; we'll follow it". Everyone in Brussels and, frankly, I think I would suggest in Ottawa too, are willing to move forward with regulation. But they are very eager for Facebook and others to do their part too. So, Zuckerberg came in with this message of, "We'll do whatever you tell us". The response was, "That's great, but there're some steps you can take yourself, which you're not doing". And, frankly, Facebook didn't really get that. There was a sentence that, "We're here to play our part". The Commission were like, "Okay, fine, but you're not doing enough on your own".

Taylor Owen: It’s interesting, I assume he brought with him a copy of the white paper they released the next day. That was probably the framing of those conversations.

Mark Scott: Exactly.

Taylor Owen: And it felt to me like that white paper, particularly on the harmful speech side, position some core issues in a way that were strategically advantageous to Facebook. I'm thinking of there being global standards rather than national ones. Which bumps up right against how EU member countries have been regulating the space to begin with and bumps up right against how the statement today is talking about national policy experimentation and regulatory experimentation. Right?

Mark Scott: I mean the cynic in me thinks turkeys are never going to vote for Christmas. So, I think there's a legitimate point to say we need global rules because you and I don't want to be having a different form of the internet no matter where we're based. The problem with that is, to your point, domestic rules and moving forward and even today you had at least in the German cabinet passing updates to their own domestic hate speech rules, which will likely come into force by the end of the year. So, I think Facebook saying, "We need global rules", plays well to the masses and it plays well to the shareholders. I just think that is significantly off where most of the policy discussions are happening, both here in Europe, and I would suggest also in Canada.

Taylor Owen: And part of me always struggles with the need for global standards around speech because of all the regulatory actions in the tech space speech is something that has always been entrenched in national law. And for really important historical reasons we govern speech in totally different ways in different countries. Their disconnect there seems pretty vast.

Mark Scott: I would agree. I think that kind of plays to the point where Facebook is slightly, doesn't get at least on outside of the US the nuances that are required to do this stuff. Again, I have some sympathy for Facebook looking to have global rules because it would make everyone's life easier. But to your point, that is not how this works. You look at what's going on in Germany, France, the UK, even down to Singapore, and it's fake news. These things are happening domestically and if you don't respond to them quickly, you're going to get left behind.

Taylor Owen: One last thing on the white papers that caught my attention was, this focus on not doing absolute takedowns for all flagged hate speech, but focusing instead on the amplification of it and having thresholds for the reach and velocity with which things are spreading? And that those are subject to take down? Do you have any thoughts on that and how that might've been received? Because I think that's actually getting at some of the nuance of this conversation. That its algorithmic amplification that might be the challenge. Not any one person posting to five people.

Mark Scott: I think you saw that slightly in the crusher. It's called fallout. The idea being that, if you reduce amplification, you can solve, if that's the right verb to use, some of these issues. There is sympathy for that argument. It's aggression of who sets those limits? How do you police them? And then, in certain national capitals, I think people want just a categoric take down because, even if it's being seen by five people, for some politicians that's too much. So, I think that the nuance is there. Will it play well with politicians, many of whom have to still sell this to voters? I don't think it will.

Taylor Owen: And it might happen. Actually, open the door to holding the algorithms themselves accountable and to some transparency on them.

Mark Scott: I think that's the next step. I think you will see significant moves on, I mean, per the European Union's announcement today, when it comes to at least on the AI side, the algorithms. There's definitely going to be a push for greater transparency, more ethical oversight auditing that will be coming.

David Skok: You had George Soros, the financier, writing in the Financial Times, calling for Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg to step down. You mentioned the Christchurch call. I'm thinking of the proxy that was done, started by the New Zealand super fund to get investors to rethink their investments in some of these companies. Beyond the regulatory political realm, has there been conversation on the corporate social responsibility and the role that they can play in alleviating some of these concerns?

Mark Scott: Frankly, no. I think some of that is because, at least here in Europe, the business community and the policy making community don't talk to each other. So, the idea of providing some sort of CSL role or shareholder accountability is not part of the discussion now purely because politicians are making those links nor investors themselves. I haven't checked the share price today, but I would, I think most of the big tech firms are at record highs when it comes to the stock price. So, I don't see how this increased regulatory oversights or proposals have affected their bottom line yet.

David Skok: In fact, when they got their fines from the feds, Facebook stock shot up.

Mark Scott: Exactly.

Taylor Owen: Aside from the visit and the announcement, there was also a package of AI regulatory plans laid out. Who did that and, from a distance it can be hard to sort of navigate, which committees and groups and EU politicians are doing what exactly? Who launched the AI regulatory package and what was it saying?

Mark Scott: I'm quite close to this and even I can get confused. So that's completely fine.

Taylor Owen: I'm glad to hear that.

Mark Scott: So, the way this works out is that the division of power within the European Union right now kind of spits between to commissioners. You have Vestager, who has a competition role, but broadly she is the woman pushing and is behind some of the AI proposals. They are focusing a lot on the ethical use of data, the algorithmic transparency, the potential limitations on facial recognition and other types of corporate uses of AI. So, the next step is kind of complicated. I think there is a consultation until late spring, I believe, to get sort of interested parties’ feedback. That will then lead to some horse trading and the commission will come up with some rules, probably in Q3, Q4, about what to do next. Then there's probably another two ish years of internal lobbying before we get anything on the books. So, we're looking at 2023 ish, if anything happens. So does that pop, but then it's very difficult to separate that from the data package that was announced today. And because frankly data runs the AI networks of the future. A lot of that is about opening up industrial data for specifically EU companies. I would suggest incumbents, so they can then also get into the AI game. They also have the datasets that they can pull to use and build up their own AI capacities to compete with the US and Chinese players.

Taylor Owen: So, it's a European data trust type scenario.

Mark Scott: Exactly. Yes. Under the European data trust, I believe is going to be happening, at least the proposals by the end of this year, end of 2020. But then, ironically, some of the people involved in the data trust are the US players because they have significant data center and data infrastructure in Europe. So, legally they can because, for example, Facebook Ireland and the HQ in Ireland is technically a European company. So, they can also participate in that. There's going to be some horse trading I think on the geographical domain of who can participate.

Taylor Owen: When you think of a scale of data access on both, the Chinese and US tech side, is that even realistic to think that there's a real industrial capacity here that can be built on top of this or is it just going to be too late?

Mark Scott: I think on the consumer side, it's too late. I think from the industrial use, sort of the industry 4.0, which the Germans always liked to talk about, there is a potential opportunity there, particularly form Siemens, the BOSH, the Alstom, the sort of the industrial players. You might be able to become more efficient in their business practices by using AI and machine learning. But do I expect the Chinese and American consumer facing companies to lose out on AI because of these data trusts? No, I don't. I think, frankly, this gets super complicated, but this also plays into Europe's very legitimate and, frankly, very good privacy standards. Makes it very difficult to replicate what the Americans and Chinese do because of the limitations on access to sensitive data, getting consent from individuals. That in Europe is already a stumbling block for using data in AI. And that's only going to get progressively more difficult now that the commissioner is paying more attention to it.

David Skok: Mark, I'll just ask a blunt follow up on this. You obviously you have the United States, you have China spending billions, hundreds of billions of dollars on AI technology. Then you have the rest of the G8, I guess I’ll throw Canada in there as well. Do we even have a seat at the table in this conversation? I mean, we can put up all these ethical frameworks as much as we want, but does it really matter?

Mark Scott: So, this is the question I'm asking myself. Frankly, looking at these proposals, I would like to say, yes. I think money isn't the only thing that matters. Naively I would say, I would hope there was an ethical standard that can be set. But then I also think money talks. The level of sophistication of AI already in place by some of the Chinese and US players. I struggled to see how, with the resources available to the rest of the G8, to use your example, you can catch up, particularly when you're starting to put limitations and, frankly, legitimate limitations on use of AI through ethical rules. I don't see the Chinese and Americans doing that. So, if they're running a hundred-meter race and you're running a hundred-meter race with hurdles, who's going to win?

Taylor Owen: One of the ways you can get at it, is I guess by putting actual barriers up to commercial activity from those companies in your market. And it seems like that's partly what the other report, that came out this week, the EU competition report?

Mark Scott: Yeah.

Taylor Owen: Can you actually change the way foreign companies operate in your markets?

Mark Scott: And that is the $64 million question. I think, frankly, the big question to be asking right now, because of all the rules to be put forward today, changes to the competition and antitrust rules. I would suggest that the long, the biggest potential effect of all this because Europe and its competition authority has been the most muscular in responding to foreign firms. So, if there is an ability to limit or impinge foreign actors from operating within the EU, which is, frankly, still the biggest consumer market in the Western world, that could have an effect. But even saying that it's an open question, how successful that will be.

Taylor Owen: So, just final comment, I guess, on all of this flurry of activity is, why is this happening now, and do you think this is sort of the sign of a really aggressive push happening from the EU now?

David Skok: As at the beginning of the end or the end of the beginning?

Mark Scott: I would suggest is the end of the beginning. I was asking to put that on Twitter today. But I think you beat me to it. I think it's definitely the end of the beginning. Say, in the last five years, Europe has through its competition privacy policy, stepped up to the plate in terms of regulation and has got a lot of confidence. This next five years, particularly in the package announced today, is then trying to implement that and push European agenda through tech sovereignty and a more muscular antitrust approach to the rest of the world. What I find really interesting, is that throughout this whole conversation we've had, is at no point is the US government mentioned. And without, not to knock Ottawa, forgive me, but without another Western democratic government providing a counterweight for the European proposals, I would suggest that, although they might not be perfect, Europe is going to run the gamut of policies purely because DC is MIA.

Taylor Owen: We've had a ton of talk in Ottawa about potentially stepping into this space, but not the kind of concrete movement that you're seeing in this. So, it might be that it spurs action in other democratic countries as well.

Mark Scott: I think so. And I would hope so because as much as I approved what the Europeans had done, it's not perfect. I think if Ottawa, Canberra, maybe Tokyo can step in and help, it makes everything better. But, to your point, this is a big step. But it's the beginning of a step. We should not get too carried away with ourselves because the final rules that come into place maybe very different what was proposed today. So, we'd be now a question of, "Can they put the money where the mouth is and can they sort of push back on some of the lobby efforts that are already going on to weaken these proposals to get them across the line?" And that is the question we don't know the answer to.

David Skok: Mark, we appreciate that you probably failing on deadline and that you took the time to talk to us today. Thanks so much.

Mark Scott: Thanks for having me.

[MUSIC]

Narrator: The Big Tech podcast is a partnership between the Centre for International Governance Innovation, CIGI, and The Logic. CIGI is a Canadian non-partisan think tank focused on international governance, economy and law. The Logic is an award-winning digital publication reporting on the innovation economy. Big Tech is produced and edited by Trevor Hunsberger. Visit www.bigtechpodcast.com for more information about the show.