This transcript was completed with the aid of computer voice recognition software. If you notice an error in this transcript, please let us know by contacting us here.

David Skok: Hello, I'm David Skok, the Editor-in-Chief of The Logic.

Taylor Owen: And I'm Taylor Owen, a senior fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation, and a professor of public policy at McGill.

David Skok: And this is Big Tech, a podcast that explores a world reliant on tech, those creating it, and those trying to govern it.

Taylor Owen: The first phase of this pandemic was defined by terms like social distancing and flatten the curve. But as we enter this next chapter, a new phrase has been added to our collective vocabulary, test and trace. According to public health officials around the world the best way to fight COVID-19 is through a rigorous system of testing and contact tracing.

David Skok: Contact tracing has been around for centuries and it's played an important role in containing other viruses like SARS, Ebola, even smallpox. It's essentially detective work. When somebody tests positive for the virus, you track down everyone they've come into contact with since becoming infected. Then, you tell those people to self-isolate and get tested.

Taylor Owen: It's actually pretty straight forward and it can be really effective, but it requires a lot of resources. In the United States, some experts estimate that they would need as many as 300,000 contact tracers in order to track the virus effectively. It's a massive undertaking, so governments around the world are of course, turning to technology to help. Namely in the form of digital contact tracing apps.

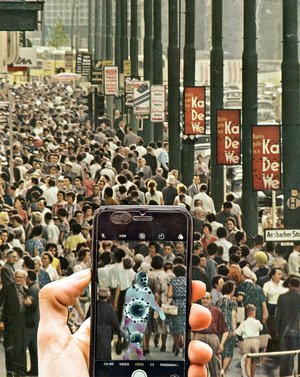

David Skok: Dozens of countries have already rolled out apps like this, and dozens more will be rolling out in the next couple of weeks. Now, while they all fall under the banner of digital contact tracing, no two apps are created equal. Some use GPS to track people, while others use proximity based Bluetooth. Some rely on self-reporting while others require a positive diagnosis and perhaps most significantly, some apps store all their data in a centralized place like an app being tested in the UK right now. Others are decentralized, which means that your data stays on your phone and doesn't go to some public health authority. The most prominent example of this is a protocol developed by Google and Apple that is totally decentralized and geared towards protecting users' privacy.

Taylor Owen: In other words, it's a bit of a dog's breakfast and there are serious questions about whether this kind of tech even works.

David Skok: So, to help make sense of all this, we sat down with Carly Kind. Carly's the director of the Ada Lovelace Institute, an organization that studies issues around data and AI. In April, they publish a report on digital contact tracing called Exit Through the App Store?

Taylor Owen: We began our conversation talking about the merits of digital contact tracing, but it turns out it's impossible to isolate that conversation from a much broader one about issues of tech governance and about shifting power structures in our society.

David Skok: So, in that report that came out in April, you found that, and I quote, "There was an absence of evidence to support the immediate national deployment of the technical solutions under consideration." Since then we've seen Australia, Iceland, that have rolled out apps. The UK has now started testing an app, several States in the US, as well as here in Canada are moving in that direction. Do you think we're moving too fast?

Carly Kind: That's a good question and I think where continually revisiting that conclusion. Is there now sufficient evidence to support the national deployment of these apps? I think, first of all, it's important to say that most of the people, almost all of the people involved in this development of this tech, are entirely well-intentioned people trying to find good solutions for immense problems that are not only public health problems, but their economic problems. The effect of the lockdown is potentially as bad as the lockdown, the kind of health impacts of reducing the lock down. So, start from the point where everybody's trying their best and trying to be well intention. I think when we published Exit Through the App Store?, We simply couldn't see the evidence to support the types of claims that were being made at that stage. That a exit strategy could hinge on the deployment of an app. There just wasn't the evidence to show that an app had been effective in any country, even though people were holding up countries like Singapore and South Korea as exemplars, there was no evidence to connect the use of a digital technology to the success in responding to the pandemic. But rather, most of the success could be attributed to other mechanisms such as very pervasive manual contact tracing, other kinds of social institutions in place. I would say that that is still the case, that we still haven't seen the evidence to support the fact that apps themselves can be an effective public health intervention around this crisis. Certainly there is no evidence to suggest that they can't be a useful compliment, but on the countries that have used apps, we find no claims being made to them being central to any success. So Iceland, for example, the head of the contact tracing system there came out and said, "The app itself didn't really sway the response in either direction. It was investment in manual contact tracing that was effective." Equally, the product lead for the Singapore Trace Together app came out and said, "The app hasn't really made the difference here. It is around manual contact tracing that has been incredibly important." I think there's generally feeling from Singapore that the app was almost a failure. So, I think there's a very kind of murky set of evidence about how important these apps have been.

Taylor Owen:

I was hoping if we could just pause for a second on the technology of contact tracing.

Carly Kind: Sure.

Taylor Owen: Can you walk through what we're actually talking about on the technology side and in particular, the different sort of levels of accuracy that are possible with Bluetooth, versus GPS, versus like, so when you think about the app on your phone that you download, what is that going to be doing to help the process of contact tracing?

Carly Kind: Good question. It depends of course, on what exactly the design of the app is, but it's fair to say that with all digital contact tracing apps, the intention of the app is to help to assess a person map out their contacts, ie people they have come near throughout a particular period of time in order to identify where they've made may have passed on the illness. And so, digital contact tracing apps have developed kind of two mechanisms for doing that. One focuses on GPS data, so physically trying to pinpoint an individual's location over a series of time, such that either the individual themselves, or potentially an outsider coming in can look back through that data and isolate where they've been in the vicinity of other people and then go and contact those people and make them aware that they may have been exposed to the virus. So that's GPS focusing on actual location. Now there's another mechanism that has emerged in this crisis, which is around proximity notification. That is around not knowing exactly where in London I was, but knowing who I came into contact with. And to do that type of contact tracing, you don't need GPS, you don't need to know exact location. What you do need to know is a proximity to other mobile phones and to do that type of contact tracing, you can do that using Bluetooth. So this is the more prevalent type of contact tracing app. Essentially, with Bluetooth enabled and using a digital contact tracing app, my mobile phone can keep a record of every other mobile phone that it has come near over a period of time, and it can keep that record until, and unless, I then start to experience symptoms at which stage it can notify all those other mobile phones that I'm experiencing symptoms and that they should also self-isolate. That's the kind of theory of digital contact tracing. In terms of the kind of problems and limitations. With GPS, there are a range of limitations. Some of those are around specificity of GPS data. What level of detail can you get to in terms of where an individual is? And then, if they go into buildings, if they go into the Metro, the underground, et cetera, how much of that data do you actually lose? On the Bluetooth side of things, the technical limitations are around how specific, in terms of a level of detail of distance between mobile phones, so under most countries, public health rules, they need to know when an individual has come within one to two meters of another individual and Bluetooth acts as a proxy for that distance. But, research shows that Bluetooth isn't great at necessarily detecting that level of specificity, essentially. So it might not work for example, for distances less than five meters. There's also the concern that Bluetooth, for example, might work through thin walls. So, if I have a thin wall between my neighbour and I, my Bluetooth detects proximity there, so those are kind of base level technical limitations. There's a kind of second level technical limitation of contact tracing, which is around, if you were doing manual contact tracing, you might say to a person, "Okay, well, how close did you stand to your neighbour? Were you inside or outside? Was the wind blowing?" You'd ask all of these types of questions to, in order to understand, was this a contact, or was it not? Whereas with a Bluetooth type proximity system, all you know is that their mobile phones were near each other other.

Taylor Owen: Beyond the Bluetooth, GPS distinction, there are other ways these technologies differ from one another, right? One's to do with how they're actually storing their data. Where they're storing it, how they're storing it. Can you explain that distinction?

Carly Kind: In the UK, the NHS is developing its own bespoke digital contact tracing app. That has kind of raised a range of controversies around where the data is stored. So, on some proximity, tracing apps, Bluetooth apps, the data is stored in an anonymized form on an individual's phone. In the NHS system, the data is stored at a centralized level in a pseudonymous form. The NHS has argued that that's preferable because it allows them to make adjustments to how they make decisions about some of those issues I raised earlier about length of time that you'd need to be near somebody, proximity, and all the other kinds of factors that feed into whether or not a contact is actually a contact. NHS is arguing that they're better able to adjust that as new information comes to light, if they have the data stored at a central level.

Taylor Owen: Okay, and that's that's in juxtaposition to a more decentralized architecture. Right?

Carly Kind: Absolutely. Yeah. So, the there's a big conversation about whether or not you can achieve the same type of functionality with a decentralized version. The decentralized version means everything's stored on your app, no data shared with anybody else.

Taylor Owen: And that's what Apple and Google are providing, were offering, right?.

Carly Kind: That's the Google and Apple system that they've developed and built, and there's a lot positives in favour of that system, I think. What is really important for ordinary people that don't spend their days talking about decentralized, versus centralized systems, is that one thing it does implicate is how trusting people are in the system. With a decentralized system, less data is gathered, with a centralized system the state has access to more data, albeit potentially in a very privacy preserving way, but has flow and effects for whether or not people feel that they want to use the app. That gets us into this whole other challenge around digital contact tracing, which is arguably more fundamental, which is you need a minimum threshold of people to use a digital contact tracing system in order for it to be effective at all.

Taylor Owen: What number, what percent is that?

David Skok: What is that minimum?

Taylor Owen: Yeah, sorry, right. We both want to know.

Carly Kind: That's a really good question. So, you probably have had this 60% number, so the optimum number is 60%, and that's based on modeling done by the Oxford big data group, which found that 60% of the population, which is actually 80% of smartphone users, would have to use a contact tracing up in the UK in order for it to be effective in suppressing the virus. But, as research coming out, I think it's Frank Dignam, he published an interesting paper in which he was saying that it's not sufficient to talk about 20%, or 60%, of a population. That 20 or 60%, needs to be evenly distributed across the country. If you had 10% of the UK population download and use the app, that would be about 6 million people. If those people were all in London, Newcastle or Durham or Manchester, would not get any benefit from the use of that app, it would clearly have to be distributed more evenly.

David Skok: So, whether you have a Bluetooth app, or whether you have a centralized or decentralized app, at the end of the day, if I'm understanding you correctly, you still need the adoption.

Carly Kind: Absolutely.

David Skok: So that's, now a wonderful segue for me to talk about U2. Many years ago, U2 had their album downloaded onto every Apple phone, much to the dismay of people who were not fans of Bono. Apple and Google have said that they're developing an exposure notification tool. In terms of the adoption, what advantages could Apple and Google bring to this given their sheer scale?

Carly Kind: Yeah, really interesting question. So, it's true that the NHS app that's under development, there have been some suggestions coming out from the trials that it drains the battery. For example, because the app can't operate in the background, it has to operate in the foreground. Now, that is absolutely a problem unique to a bespoke system, it will not be a problem experienced under the Apple and Google protocol because they control the hardware and are able to fix those problems, so I think that's one point. I think what your question is otherwise alluding to is, essentially this question of whether or not this type of app would need to be mandatory, or kind of heavily suggested, including through an automatic update in order to be useful. I think that there is a strong argument that if digital contact tracing was an effective mechanism, if you could solve the technical limitations and mitigate their social considerations and concerns, there would be a strong argument in favour for going that route. That is automatically sending an update to everybody that required them to download the app, whether or not you'd get them to then use it as another question. But, if we agree that an app like this could be effective, it must be in the public interest for as many people to use that as possible, and for us to use all methods, kind of short of coercion, for them to use that. But, I do think the problem there is, we don't actually have the evidence to support that it's a useful, or effective tool, in the first place, or that those negative social impacts could be mitigated. I would be very uncomfortable supporting that position now, but if we could get to a place where he thought, actually this is super important, and everybody should be using this because all of our fates are tied up together, then using that system would be, I think, the best way forward.

David Skok: What kind of guarantees are being discussed around time limitations of when this would be used? I mean, it was once, the natural argument from privacy experts is, "Well, once we go down this road, it will be really hard to put the genie back in the bottle," are the app creators putting in place some guarantees that will appease privacy experts?

Carly Kind: I wouldn't go that far. I would say, I'm a lawyer, so I guess I start from the perspective of it would be better if it were in law. I think that the better way to give those guarantees would be some type of legislation with a sunset clause. So, in terms of what protections would be best, I think firstly, technical protections, that is you can just delete the app and therefore delete your data. That would be the best way that would place the most control in the user's hand. Beyond that, I think, some type of watertight legal protection requiring the app makers and users to delete the app at the end of a particular period. But to be honest, I think that the concerns are probably much more fundamental than just, "Will I have to keep using this particular app, or will I get my data deleted?" I think it's really about how society is going to transform more fundamentally into higher levels of tracking, and requirements to disclose information about one's health status, and kind of submit to more intrusive levels of state monitoring, as we work out how to deal with this crisis in the long-term.

Taylor Owen: Like a lot of these tech adoption trade-offs, it often comes down to whether you think those bigger structural changes, and potential negative changes, can be offset enough to adopt the utility these tech can provide, right? Where do you fall on this now? Do you think we should, there's so many limitations to this, clearly. There aren't many protections being built in yet, legally. Do you think without those, we shouldn't even bother?

Carly Kind: On digital contact tracing, it's not so much I remain unconvinced, I remain quite pessimistic about how useful it will be. And in kind of concern that we're putting too much faith in it. Certainly in the UK, there's quite a lot of disagreement about at what stage schools should reopen, for example. For a while, the government was saying, "Provided the app is in place, then we will reopen schools." As if the app is the silver bullet that will make schools safe. And I just think that...

Taylor Owen: As opposed to a bunch of six year olds running around.

Carly Kind: Exactly.

Taylor Owen: Spreading germs with each other, yeah.

Carly Kind: That raises a whole another question, right? About, if kids don't use these apps, how do we make sure that we're tracking contacts and this. And, we haven't even talked about those that are digitally excluded in the elderly, who are also the most vulnerable to this disease. But, so I think that there's that kind of putting the hopes on the app is for me quite worrying, and I just remain unconvinced that we're going to get through all of the technical glitches that make it work. In contrast to that, I think this question around immunity apps, and health status apps, has more mileage in some respects, in terms of, to your point Taylor, about how we do these trade-offs around, there may be genuine utility in someone being able to say, "I can get on that plane because I've had this disease and I can prove it," and I want to go and see my family in Australia. Which is the situation I'm in, for example. There may be genuine utility to that. And some of the technical limitations of contact tracing don't exist. There you're just talking about a simple kind of digital identity system. There, we need to think really hard about the long term infrastructures that we're going to establish and the precedents we're going to set. How can we design a system that enables people to use that type of verification, but don't also end up in a situation where people are stigmatized for that same health status, or prevented from moving in certain places, or returning to work because they can't show an immunity status, or immediately passport. I think that's the precipice on which we stand. Which is, we now need to stop trying to plug holes with apps, and we need to think fundamentally, what is the society going to look like for the next few years? What technical infrastructure might help us design a better society that's more inclusive? How do we get there in a way that brings everyone along for the ride and avoid the kind of scaremongering, but also the techno-solutionism that we've seen at various points in this crisis? And find, mediate, a middle path that genuinely brings people in and along for the ride.

Taylor Owen: Part of that bungled rollout seems to be the application of geopolitics on top of this too. And I wonder if you can help explain what's going on with the EU on this right now. I mean, just today, I saw a piece that five of the biggest countries in Europe are criticizing Silicon Valley for kind of imposing their technological infrastructure on Europe. At the same time, you're seeing these national deployments by the most privacy conscious democracies in the world that are arguably far more centralized, and far more egregious in terms of data collection. How do you balance that? Like what's going on with European countries right now? What's up with Europe?

Carly Kind: Good question. It feeds into, I think, a broader trend that we've seen in Europe in recent, well, certainly in recent years, around de-tech-regulation, and competition, and all the rest of it. But, if you look at the European data strategy, which they published I think in January, and the AI white paper, there's a real sense in those documents that the social value, or public value, of data has been exploited by the tech companies, and hasn't been exploited by governments. That they've kind of missed the boat on how to work out, how to use data in the best way. That companies have achieved that to the detriment of governments. I think that this is a kind of fault line that's been exposed somewhat by this crisis, which is governments feel like they're at a disadvantage when it comes to using data, using technology, and tech companies have the keys to unlock all the potential of data, or the potential of technology. I think that that is actually something that we should sit with it, and I think as we go into this new phase about, is there a way to reapportion access to data that helps us realize its social value?

David Skok: Carly, the data analytics from Palantir recently partnered with the NHS as part of their coronavirus response. Palantir is controversial for a number of reasons. The most recent being that ICE was using their software to facilitate mass deportations in the States. What are the implications of this kind of partnership and how do we, as citizens, remain vigilant about adopting some of these tools when these tools actually might be helpful in the short term?

Carly Kind: Yeah, that's a tough one. I think that it's very difficult for citizens to take a position that's fundamentally for, or against, particular companies working with particular government agencies. I think that we have to try and engage citizens in the nuance of those conversations. Which is not about demonizing, necessarily, public-private partnerships, which many of these are, but which is thinking about how to structure them in a way that gets benefit to individuals, protects against abuse, and ensures that the value created remains with the public bodies and public institutions. People can hold more than one idea in their mind at the same time. I think that people can appreciate that the public health system can derive immense value from collaborating private companies. That they bring things like specialist algorithms and research, and advanced technology that could be brought to bear in the health system, and that there's a value exchange that happens there. But I think there's a real worry that that's not a fair value exchange and that companies inevitably win out. I think with Palantir, for example, one of the concerns is that they're charging one pound for the whole contract with the NHS. Now, it may be that they're doing it out of the good of their heart and they're coming to aid in a crisis. Undoubtedly, there is value they derive from that contract. I think making that explicit helps to build public trust and confidence, and eliminates the sense that there's backroom dealings going on that makes people suspicious of these types of things. I think it's unnecessary cloak and dagger if you ask me, I think they could be more upfront about this. So, I do think it's more complex than just bad companies, good companies, government and private sector, good or bad, et cetera. I think there's an interesting collaboration between the two that can be really fruitful, but from a kind of public accountability perspective, we need a lot of transparency around that.

Taylor Owen: Yeah. And while there's a fair amount of differentiation between some of these companies, what's clearly undebatable is that some of them are getting a lot bigger right now. We had a fascinating conversation with Joseph Stiglitz recently, where he was talking about the parallels between now and the great depression. His argument was that it wasn't just the companies were getting bigger during that period, but that they were also getting more politically powerful. That was actually the combination that triggered an era of antitrust, this combination between economic power and political power. I wonder if you see this happening again, we've been hearing for a long time that big tech wants to get into the financial services and healthcare sectors, because these were sort of the last big stores of data that they could get access to in society. Well, it looks like some companies are getting a pretty big window into the healthcare data space right now. That a consequence of some of these public-private partnerships we're talking about., is that the relationship between tech and political power is becoming even closer. I'm guessing I'm wondering, is this something that concerns you?

Carly Kind: Yeah, I think that's a really, really good point. I think it's hugely concerning. And it's doubly so, given at least in Europe and I'm sure in North America, we're finding that governments will be gutted by this crisis, actually, financially and will look more and more to the private sector to take on aspects of provision of public services potentially, or other aspects in order to help us emerge from what will be a very deep recession. I think there is something about focus on data, and then there's something about infrastructures, and digital infrastructure. So, I think, there's a question around access to data, who has it, who's able to use it, and how they're able to profit from that and gain power. I think that if the result of this crisis is to give more of that data to big tech companies, we see an entrenching of existing problems and even more difficulty in digging our way out of that. Equally, I think there's a kind of, who designs infrastructure, who controls infrastructure question? And, this is why the Google and Apple protocol is so interesting because, from a purely privacy perspective, you can't help but think it's a great solution from a power and control perspective. You can't help but feel somewhat afraid that two companies control almost every device in every hand in the world, and are able to wield that power in ways that contradict, right or wrong, the desires of national governments, and public health authorities. I think that that's scary and, Taylor you're right, that we see this as a huge opportunity for them to entrench those positions. I'm not sure what the way out of that is. What I think we probably need is a more fundamental vision for how things need to change now because the current path we're on looks only to be exacerbated by the crisis unless we have a different path to move towards. And so, you brought up monopoly, I think we need to... Problems of anti-competitive behaviour are certainly only going to get worse when big tech companies get into the health sector. So, I think that necessitates a much stronger rationale for getting into anti-monopoly regulation sooner, rather than later.

David Skok: It's really remarkable that we can start our conversation talking about contact tracing and the technology and specifics of that, and then roll into privacy, and then roll into marketplace and competition. And then, strap on a little bit of geopolitics as a kicker on top. That's kind of a remarkable statement of where we are in this moment, and how much is encapsulated in decisions that are made very incrementally that could have such far reaching implications. I guess, for my last question, I wonder, I read a piece by Atul Gawande in the new Yorker that talked about masks. Just straight up, old fashioned, paper surgical masks, having a 90% or 95% protection rate if everybody wore them. Then I listened to you talk about the lack of effectiveness, quite frankly, if I'm not misunderstanding you from contact tracing. I have to wonder all of this hope and technology, is it misplaced? Are we better off thinking more about old technologies as opposed to new ones?

Carly Kind: What a time to ask it, when all we do is interact with each other via technology. I feel positive about technology. I think it's enabled immense benefits and this has been the most amazing time to witness how digital transformation can happen overnight when it's dragged on for many years. But, I would say that we need to be very, very careful, more careful than ever, about the lure of techno-solutionism. I think that this crisis, to me, has revealed just how strong that drive is to want to fix things with apps, to put it really simply. My colleague Reema Patel loves to give the analogy of a washing machine. The washing machine was sold as a means to liberate women from domestic household chores. I think that most women alive today can say that that wasn't entirely achieved through the introduction of the washing machine. I think we need to be very careful when technologies make some aspects of our lives so much better, not thinking that that necessarily applies across the board, including in fighting pandemics. Not to add in another layer of complexity, but I do think there is a very real risk that a strapped cash incomes will push us further towards techno-solutionism than away from it. Particularly when you think about the potential for risk scoring, or other types of algorithmic systems to be applied in public services and the delivery of welfare benefits, et cetera. I think we really risk going down that path. So, in addition to trying to find a new positive vision for a data governance ecosystem, I think we also need to work out what is the messages that really break through about how technology won't solve everything and how you can send those messages without sounding like a Neo-Luddite, which is another part of the problem. How to make them politically palatable for a policymaker to say, "Actually, we don't think that an app is the solution here. We think hiring 20,000 manual contact tracers is actually the solution." And, how do you remove whatever invisible pressure seems to be there for them to always say that technology is the solution here. I think those are some more fundamental questions that I'm grappling with.

David Skok: It's been a real pleasure to chat with you and, and no doubt these things are going to be more complex as this conversation has illustrated for all of us. So, thank you for your time.

Carly Kind: Thanks for having me.

Taylor Owen: Big Tech is presented by the Centre for International Governance Innovation, and The Logic. And produced by Antica Productions.

David Skok: Make sure you subscribe to Big Tech on Apple podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. We release new episodes on Thursdays, every other week