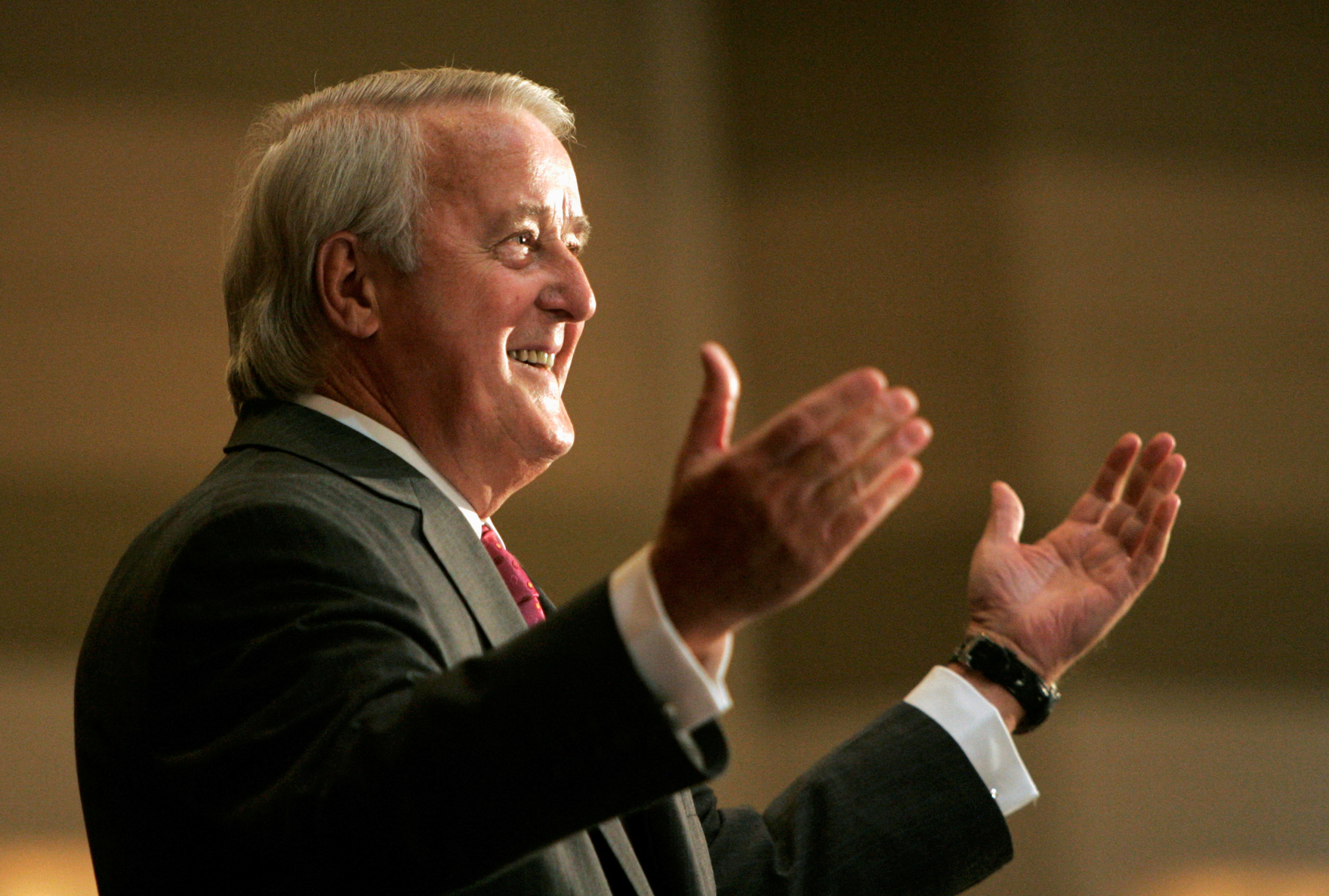

By the time Martin Brian Mulroney stepped aside as prime minister of Canada in 1993, he was among the most polarizing — some would say reviled — people in the country. From that day on, he told friends, confidants and journalists that any leader who tackled the biggest problems was bound to make a lot of people unhappy. Unpopularity, Mulroney believed, was the price of leadership.

What’s remarkable about this view of his, which became a lifelong mantra, is that he was a naturally gregarious, friendly man who appreciated being understood and liked. The opprobrium directed at him by so many of his fellow citizens, despite his having led the country capably and courageously through a tough and tumultuous decade, had to have wounded him. But that never prevented him from making bold — even risky — moves when he thought they were needed, which was often.

Others have written at length about Mulroney’s pivotal leadership in securing the Canada-United States Air Quality Agreement (“Acid Rain Treaty”) with then US president George H. W. Bush in 1991, which set a new standard and model for international environmental agreements that followed. They’ve written about his unwavering and contrarian (within the conservative circles of his day) opposition to South Africa’s racist system of apartheid, through the 1980s. And they’ve chronicled the extraordinary political risk Mulroney ran at the end of his first majority mandate from 1984 to 1988, when he staked his re-election on the Canada-US free trade deal, which later grew to include Mexico, in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Less understood, perhaps, is the way Mulroney manoeuvred the United States, initially under President Ronald Reagan and then the elder Bush, into that first monumental trade deal, applying a combination of his personal charm, volubility, natural negotiating skills and a hard-headed sense of realpolitik.

Facing a surge of protectionist sentiment in the US Congress in the early 1980s (not unlike today’s climate), Mulroney judged he needed to move Canada under the US trade umbrella, where export access to the vast American market would be assured. He did this by persuading America’s leaders that free trade was in their country’s best interests, too. The fulcrum for that persuasion was Mulroney’s understanding of — and friendship with — Reagan, who was an idealistic, freedom-loving libertarian.

It’s quite true that Mulroney deeply admired America and Americans, as has often been written of him, sometimes disparagingly. It’s also true that he appreciated — to an extent, seldom acknowledged — the extreme vulnerability of Canada’s position nestled next to its gigantic, insular superpower neighbour. It was Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau who famously said that “living next to [America] is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.”

Consider that this was a former Conservative prime minister, still active in the party, offering concrete aid to a Liberal government, at a time when Conservatives in Parliament were taking opposing positions.

Although Mulroney never publicly articulated the problem quite that way, he privately lived it and made it foundational to his leadership. He carried this mission with him, applying great energy and effort to protecting Canada’s economic and geopolitical interests, long after he’d formally retired from public life.

In 2017, when then president Donald Trump was preparing to rip up NAFTA and impose import restrictions that would have crippled Canadian manufacturing, Mulroney stepped up to help. He had an encyclopedic — and still very current — knowledge of the US political scene, in Congress and across the country. He particularly understood the populist movement that was transforming American politics. He knew many of the key players, including Trump himself, personally. And he applied both his knowledge and his contacts in ways that helped Canada.

Consider that this was a former Conservative prime minister, still active in the party, offering concrete aid to a Liberal government, at a time when Conservatives in Parliament were taking opposing positions. In the context of saving NAFTA, Mulroney simply did not care about domestic political considerations. He was all-in for Canada, without apology, without reservation.

The Government of Canada’s strategy in 2018, as it worked to shoehorn a new NAFTA into being, despite Trump, was infused with Mulroney’s experience and insights. Its operating principle was that Americans, when made aware of the critical role Canada plays in ensuring American prosperity, not just via interlinked supply chains but as a purchaser of American goods, would ultimately choose to preserve continental free trade. They did.

Today, as Canadians face a reflexively protectionist Democratic Party and the possible return of Trump to the White House, with all the turmoil this would entail, it’s impossible not to reflect on the great gulf that separates us from the era of Mulroney and Reagan. And it’s impossible not to mourn the passing of a man who led with reason, a sense of compromise, wit and a vast ambition to better the state of his fellow Canadians.

This piece first appeared in The Line.