What happens when artificial intelligence (AI) becomes even more integral in our lives than it already is? The ArriveCAN debacle is a teachable moment in this regard. Auditor General Karen Hogan found multiple violations in the procurement, development and deployment of the application that mistakenly sent tens of thousands of Canadians into quarantine and, according to some legal experts, violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

More shockingly, Canada’s border authorities lack documentation to show why the app cost taxpayers $59.5 million. In the Netherlands, an AI-driven application secretly deployed by tax authorities mistakenly flagged thousands of people for tax evasion and caused some families to temporarily lose custody of their children.

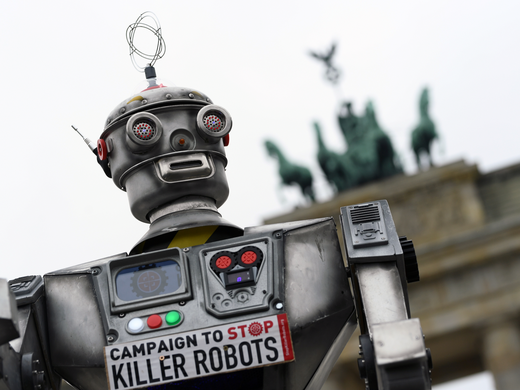

Such cases confirm that the governance of algorithms comes down to plain old democratic governance. Technology products are routinely black boxed for commercial reasons. This practice cannot be allowed to stand: when it comes to AI, the looming harms, from misinformation to disrupted elections to erosion of our democratic institutions and way of life, are simply too great.

To that end, Canada will soon renew trade agreements with key partners, and the question of whether to regulate AI is sure to arise. While the country would likely benefit from free trade in AI, there should exist robust mechanisms of accountability and redress for these systems.

A case in point: in 2022, British Columbia resident Jake Moffatt visited Air Canada’s website to book a flight to attend his grandmother’s funeral. Conveniently, the airline’s chatbot was there to help him understand its bereavement policies. The chatbot advised Moffatt to purchase tickets at full price and then submit a claim for a refund. But as he soon found out, the chatbot had misled him: Air Canada did not have retroactive bereavement policies.

The airline declined to take responsibility for the algorithm’s mistake, instead insisting its customer should have double-checked the information provided by the chatbot. Moffatt took his case to the British Columbia Civil Resolution Tribunal and won. Two years later, in February 2024, the tribunal ordered the airline to pay Moffatt the difference between the regular fare and the bereavement fare: $650.88 in total.

As a practical matter, Moffatt v. Air Canada was framed to decide whether a person or entity could be held legally responsible for the actions of algorithms they deploy and the limits of such liability. Air Canada denied any responsibility for the algorithm’s actions and even claimed that the chatbot was a separate legal entity. But the tribunal ruled against the company.

In the 2019 edition of a classic monograph, Sookman: Computer, Internet and Electronic Commerce Law, Canadian lawyer Barry Sookman provides several additional examples in which courts decided liability could not be avoided through automation of business practices (for example, Century 21 v. Rogers Communications).

But this isn’t solved, just yet. While such rulings may seem reassuring, we can’t rely on courts to address all the challenges brought on by automation. In the European Union, Google, Meta and many other large technology companies placed their European headquarters in Ireland, a country well known for its lax and business-friendly legislation. Since the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into force in 2018, very few individuals have been able to prove in court that they suffered damages from the actions of technology companies.

Indeed, European lawyer Max Schrems and his non-profit European Center for Digital Rights (noyb) have published a large database of cases, which shows that European data protection authorities rarely enforce the GDPR. Only 3.9 percent of the cases receive legal determination. Of the more than 800 cases that noyb filed in 2022, 85.9 percent were not decided.

At the same time, recent court rulings in Canada and the United States show that technology companies are getting better at protecting their interests in courts, and that the existing laws have significant blind spots when it comes to emerging technologies. For instance, the case of Canadian educator Ian Linkletter has made international headlines. Arizona-based company Proctorio brought a SLAPP, or Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation, case against Linkletter when he raised the alarm about its exam-monitoring software, which collected sensitive information about the University of British Columbia’s students (for example, by scanning their faces).

According to a 2024 PwC survey, the adoption of chatbots has been limited so far. Yet 70 percent of CEOs surveyed expect that, within the next five years, algorithms will improve their products and services.

This is a matter of urgent public interest. In the absence of oversight, millions are being spent on malfunctioning digital products and citizens are being subjected to unfair treatment. Creating an algorithmic registry might be a good way to make the invisible harms visible. As things stand, Canadians’ fundamental rights are unprotected in the digital realm.