There were many news stories about US President Donald Trump’s campaign rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma — and for good reason. First, it was planned for Juneteenth in a city where a race riot and massacre in 1921 had destroyed what was known as Black Wall Street. Following an outcry, Trump’s rally was rescheduled to the following day, June 20. Second, epidemiologists and experts warned against a mass gathering indoors because it could be a super-spreader of COVID-19. Third, Trump and his team boasted of enormous registration numbers.

But articles on the day after the rally focused on something completely different — TikTok, a video app. It seems that many teenagers, who organized mainly on the app, requested a ticket to the Trump rally, fooling Trump’s 2020 re-election campaign manager, Brad Parscale, into crowing about more than a million sign-ups for the event. Aside from embarrassing the Trump campaign and undermining its attempt to mine data on potential voters, this prank reminds us how users can inventively game platforms for their own agendas.

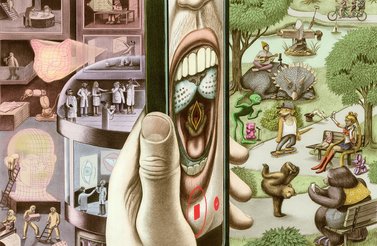

The incident highlights the crucial importance of TikTok. A Chinese-owned app that algorithmically selects short, mostly dance- or music-related videos to present to users, TikTok has consistently ranked as one of the most downloaded apps since 2018. The app has been downloaded more than 1.5 billion times, has 800 million monthly active users and is the seventh-most-used platform on the planet.

Considering TikTok — in the same light that we consider Facebook, Twitter, Amazon or Apple — can do more than create awareness that another large platform is in town.

In some ways, TikTok “recreates the regulatory challenges that came before it,” as Jesse Hirsh has noted. They include privacy concerns, harms from online content, and growth at the expense of content moderation. But there is one crucial difference, at least for US lawmakers — they are dealing with a company not mainly based in the United States and not created on American free-speech ideals. TikTok has, ironically, made it clear to US-based politicians and officials how other countries might feel about companies like Facebook or Google.

At present, TikTok rarely grabs policy makers’ attention. Some senators have raised concerns about TikTok as a national security threat, while the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States has been investigating the platform since last autumn. Nevertheless, compared to Facebook or YouTube, the platform is barely mentioned in congressional hearings. Unlike the other major platforms, TikTok was not even invited to testify in a British inquiry about COVID-19 misinformation in April.

As TikTok inevitably rockets up the agenda, it highlights some serious flaws in our current approach to platform regulation. First, algorithms are increasingly significant. TikTok surfaces content almost exclusively through algorithms. We do not understand and cannot investigate why certain videos are featured heavily, why some TikTok videos go viral and, crucially, what is suppressed. If regulation focuses on taking down or leaving up content, it will miss that content barely matters on TikTok if the algorithm demotes it. As Renee DiResta argued back in 2018, free speech is not the same as free reach. Without algorithmic accountability, we simply do not understand how platforms may be lifting up certain political or other points of view, while suppressing others without actually deleting them.

Second, greater transparency should be a prerequisite for platforms. I have previously argued that platforms should operate under a precautionary principle. Doing so would mean moving slowly and ensuring that changes — product or policy developments, for example — will do no harm to anyone before they are introduced. We might also consider what transparency is required before a platform can even put its app on the market. Might platforms be mandated to perform algorithmic impact assessments, as the Canadian government requires for its own initiatives? Might platforms be required to have tiered regimes of transparency to allow different types of access to regulators, researchers and the public so that they can better understand data and why content is moderated as it is? A new report for the European Parliament suggests that platforms should improve their “procedural accountability” around illegal content online. Meanwhile, Mark MacCarthy has laid out a detailed model of a transparency regime that could work on both sides of the Atlantic.

Third, any regulation has to account for the rapid and unexpected emergence of non-US-based platforms. The US government now finds itself confronting problems that other countries in the world have faced with Facebook and other US tech giants. It has to contemplate how to hold accountable companies not based in the United States. To create greater understanding, US lawmakers may want to ask themselves how they feel about TikTok and consider that other countries may feel similarly about US-based platforms. In an ideal world, that exercise might create more empathy for other countries — such as New Zealand, Canada or Germany — that have struggled to regulate American-based social media companies.

Democrats, at least, are showing signs of wanting to cooperate on platform governance. In mid-June, Democratic Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi offered the opening remarks for a virtual meeting of an International Forum on COVID-19 Social Media Disinformation that included officials from the European Union, Canada and the United Kingdom. Countries have already grappled with the role of TikTok: the Indian government banned downloads of the app for three months in 2019 because of fears around the spread of pornographic materials. As countries are now grappling with TikTok’s role in issues like elections or cyberbullying, there may be even greater space for international cooperation over platform governance than there was when almost all social media platforms were American.

TikTok itself seems to be increasingly concerned that its appearance is of a legitimate company that adheres to European and American rules and norms. The company recently hired an American chief executive, and it has just signed on to the European Union’s voluntary Code of Practice on Disinformation. But we have yet to consider the full ramifications of the platform’s massive growth. For example, will the company comply with Germany’s Network Enforcement Law (NetzDG) once it reaches more than two million unique users in Germany (the threshold for complying with NetzDG)? Will Germany ban the app, if TikTok does not?

Considering TikTok — in the same light that we consider Facebook, Twitter, Amazon or Apple — can do more than create awareness that another large platform is in town. It may help lawmakers in democratic countries make common cause around platform governance, at a moment when international cooperation is sorely needed.