Public comments about the Bank of Canada’s communications have not always been kind.

I confess to having described the institution as a “black box,” “opaque,” and the least transparent of the major central banks.

But it may be time to revisit these conclusions after the central bank, in a break with form, threw open its doors, and lured critics — me among them — to a day-long conflab exploring transparency and communications, as well as the central question of the right role and objectives of monetary policy. The conclusions will inform its research agenda ahead of the next scheduled review of the Bank of Canada’s mandate in 2021.

I eyed my invitation to the event somewhat warily, as a trap of sorts, meant to mollify and mute critics, but I have nonetheless stepped into it with eyes wide open — and am offering up concrete steps the bank can take to improve transparency.

The latest kerfuffle over the institution’s mandate dates from about a year ago, when central bank watchers were making a fuss over how little public debate had occurred ahead of the twice-a-decade review of the Bank of Canada’s mandate in 2016.

Commentators — myself included — were a bit late; the decision had essentially already been agreed by the governor and the finance minister.

That was a shame — but the absence of debate wasn’t necessarily the Bank of Canada’s fault.

It had launched its review with some fanfare two years earlier — and published ample background material.

And yet the financial press had written very little about the review. Those of us with access to op-ed pages waited until the last minute to stir interest. Arguably, the failure to properly examine the central bank’s mandate rested chiefly with the House of Commons finance committee, which sidestepped the issue entirely.

The Bank of Canada probably felt that it had done its part in starting a discussion.

But the question remained: Should a public institution as vital as a central bank have an obligation not just to try to stimulate discussion but to do a better job of delivering results when it comes to engagement?

That’s the view of Stephen Gordon, a professor of economics at Laval University in Quebec City, who has sounded the alarm about the risks of waiting for the public to one day waken and embrace the view that unaccountable institutions are making their lives miserable. Gordon voiced his concerns following the referendum on Brexit, after an eleventh-hour public warning by Bank of England Governor Mark Carney about the economic fallout of leaving the European Union failed to sway voters.

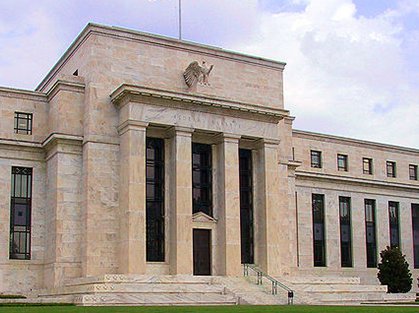

Ben Bernanke, the former chair of the US Federal Reserve, has acknowledged regret that he did not do more to engage the public before the onset of the financial crisis.

Instead, most Americans learned about the awesome power of — unelected — central bankers in real time. Many disliked what they saw.

Across Washington, on both sides of the aisle, elites are lamenting their insular tendencies, as they watch US President Donald Trump upend establishment norms.

So, the Bank of Canada is not alone in needing to rethink its opaque ways.

The fact the bank is initiating — with this week’s conference — a dialogue about its mandate a full four years before its scheduled renewal suggests the institution’s leadership is taking the question of transparency and accountability seriously.

As officials plot out the bank’s research agenda and think about what it takes to penetrate all the noise and retain the public’s trust, there is one critical step that leadership must take. It is a simple step, but one that runs contrary to central bankers’ deeply ingrained penchant for discretion.

They need to talk more.

The groundwork has already been laid. The institution is much more transparent than it was two decades ago, and it has recently introduced subtle-but-important innovations.

The statement that is read at the start of the quarterly press conferences has evolved into a useful document. Indeed, the text is starting to look a lot like minutes of central bankers’ deliberations, a big step for an institution that doesn’t keep a transcript of its policy discussions.

Governor Stephen Poloz’s decision to share the duty of delivering those quarterly remarks with Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Wilkins is itself significant — it reinforces the idea that policy is set by governing council, not by an archetypal and inscrutable governor acting alone.

The Bank of Canada has also developed the habit of delivering a speech between the release of its quarterly reports that divulges how its thinking on the economy is evolving.

These are laudable steps — but they are not enough.

Over the weekend, the Bank of Canada’s spokesperspon felt compelled to rebuke the chief economist of one of the country’s biggest banks.

That economist had called the central bank’s communications strategy ahead of last week’s interest-rate increase an “epic failure.”

The failure — in the opinion of the economist, and, to be fair, others as well— was that no one at the Bank of Canada had made any public comments between the September 6 interest-rate increase and the July 12 increase. Nor did anyone say anything after last week’s decision. And no one is scheduled to say anything until Deputy Governor Timothy Lane speaks next week.

Now, Governor Poloz said clearly in July that future policy would depend on data. Second-quarter GDP growth then came in a percentage point faster than the Bank of Canada had predicted. So, the signs were there to read.

For his part, the governor has been trying to get market participants to follow the data for a couple of years. His message to observers has been: don’t look for code words; assume we begin every policy statement as a blank page; don’t expect overt attempts to guide markets; follow the data, just as the governing council does.

But many market participants refuse to play along.

There is a very strong case that the Bank of Canada has been pretty clear of late when communicating on interest rates.

That isn’t a universally held opinion, however. Steven Ambler, of the University of Quebec at Montreal and the C. D. Howe Institute, wrote this week that the central bank is contributing to uncertainty.

Professor Ambler was troubled that only about 50 percent of the market appeared to anticipate that an interest-rate increase was coming.

He argued that the Bank of Canada should publish a conditional interest-rate forecast — in other words, provide perfect guidance.

Before contemplating such a radical move, there are two concrete steps the bank can take.

First, hold a press conference and deliver a statement on the deliberations after every policy meeting, not just at quarterly intervals. This would bring needed consistency to the Bank of Canada’s communications program.

Second, make better use of the deputy governors.

James Bullard, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, speaks about as much in a given year as the six members of the Bank of Canada’s governing council combined.

The Fed’s policy committee is sometimes exposed to the opposite critique, that its members speak too much, send mixed signals and contribute to confusion. But the approach means that market participants and the public are constantly debating Fed policy. The Fed’s audience is engaged. The Bank of Canada’s is not.

Deputy Governor Lane’s speech next week will be worth tuning into — not only because the central bank’s leaders have not been heard from in a while, but because the deputy governor almost always has interesting insight to share about the economy.

It is time we started hearing from him — and his colleagues — more often.

This article is based on remarks delivered by CIGI Senior Fellow Kevin Carmichael to the Bank of Canada.