Key Points

- The Government of Canada has long had a narrow definition of the country’s economic infrastructure, focusing its procurement on large-scale investments in tangible assets.

- Given the global economy’s turn toward non-tangible assets — commercialized intellectual property (IP) — as the greatest driver of wealth creation, there is an opportunity to update government’s technology infrastructure to generate both long-term savings and sustainable prosperity.

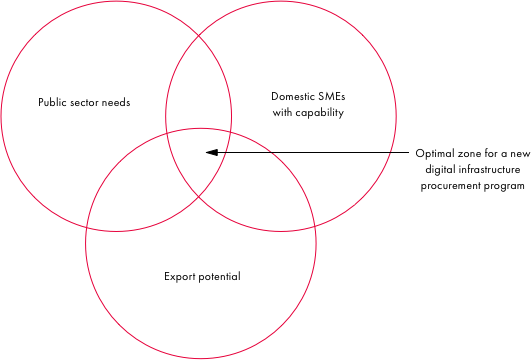

- To achieve this dual purpose, a uniquely Canadian approach will be required, with a focus on: meaningful public sector needs/challenges; domestic small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with the capability to deliver solutions; and the export potential of the solution.

overnments from the advanced industrialized world are struggling with a common challenge: anemic economic growth rates with limited monetary, fiscal and other policy levers left in their tool kits to kick-start meaningful growth. The glacial pace of these rates of growth is exacerbated by a common demographic reality. Most Western societies are propped up economically by the aging baby boomer generation. With declining natural population growth and political limits on economic immigration, productivity gains from the labour market alone likely cannot create the growth required for rich countries to maintain their current standards of living for the long term.

Further, the impact of general labour inputs in creating scalable and sustainable economic growth in the contemporary global economy is waning. There have been tectonic shifts in value creation in the global economy. Tangible assets, such as natural resources and manufactured goods, have taken a back seat to non-tangible, digital assets, such as software and other forms of IP.

These realities are especially glaring in Canada. The country’s aging population, coupled with a significant level of public expenditure in social programming, specifically health care, and relative economic reliance on tangible goods industries, such as natural resources and the manufacturing sector, leaves stagnation as a relatively optimal scenario in the long term, should the country’s macroeconomic trend lines maintain their current trajectory. While a focus on economic immigration could have a positive impact, doubling or tripling annual intakes would be riddled with practical and political challenges.

Tangible assets, such as natural resources and manufactured goods, have taken a back seat to non-tangible, digital assets, such as software and other forms of IP.

The Government of Canada has seemingly recognized these realities and taken the unprecedented step of committing to inject significant fiscal stimulus (The Economist 2016), to the tune of CDN$125 billion in infrastructure spending, into an economy that is growing, albeit at modest rates. Both the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund applauded this unconventional economic move being made, while many other advanced industrialized economies focus on fiscal consolidation coming out of stimulus programs run through the 2008 financial crisis.

While the endorsement from international financial institutions is welcomed by the Government of Canada, government officials know it is a long way from a guarantee that these multi-billion-dollar investments will, in fact, pay a dividend in the form of a considerable level of sustainable economic growth in Canada’s future. The magnitude of an economic stimulus is an important factor in jolting large economic systems. But the multiplier going forward will rely more on the strategic nature of the investments, as opposed to their size alone.

Bridges, Sewers and (Digital) Highways — Defining the Infrastructure Canada Needs

The Canadian government has long had a narrow definition of the country’s economic infrastructure, focusing on large-scale investments in things such as roads, bridges, ports and waterways. These were sage investments throughout the last generation of Canada’s economy, as much of Canada’s economic activity was generated through the export of tangible goods to foreign markets. The large-scale investments were supplemented with social infrastructure, including hospitals, schools and community centres, which helps maintain citizens’ quality of life.

With increased urbanization in Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto and other centres, the definition of infrastructure has expanded to include mass transit. The Government of Canada has also made a foray into digital infrastructure in recent years, financing rural broadband internet access for some of the country’s most remote communities. But these investments, as with social infrastructure, simply maintain a quality of life and do little to provide a multiplier for Canada’s long-term economic growth.

Given that the global economy has taken a sharp turn toward non-tangible assets — commercialized IP — as the greatest driver of wealth creation, the government must take a long look at its definition of infrastructure if it wants to achieve material and sustainable economic growth for generations to come through its fiscal stimulus gamble.

Within a review of the definition of infrastructure, there is an opportunity to update all levels of the government’s own infrastructure as a means of generating both economic efficiencies and long-term, sustainable prosperity. Beyond putting up, and fixing up, the walls of hospitals, schools, police stations and other physical places, a significant portion of Canada’s infrastructure should go to reimagining the services provided to Canadians by government and how they can be tangibly improved with purpose-built technologies.

Improvement should be clearly defined in terms of delivering quantifiable efficiencies, government jargon for long-term fiscal savings as a result of upfront productivity investments. Public sectors, such as health, education and policing, are ripe for thoughtful review processes as to how technology could redefine their organizational workflows, empowering front line personnel to focus on where they can have the most valuable intervention in the delivery of essential public services, while leveraging technology to focus on mundane, repeatable tasks with both speed and precision.

Government Procurement of Technology — A Purpose-driven, Risk-managed Exercise

Suggesting the government utilize technology to improve the delivery of essential public services it provides to Canadians every day is easier said than done. The Canadian government has struggled with procuring technology, specifically software, in recent years, to modernize its internal work and interactions with Canadians. The Phoenix pay system (Austen 2016) and the renewal of the Government of Canada website projects (Roman 2016) are two contemporary examples of the pitfalls the government has faced in procuring solutions to relatively straightforward technology challenges.

If the Government of Canada truly wants to procure modern technology to improve public services, it must first step back and examine its procurement processes.

Governments at all levels in Canada have often gotten into trouble with technology procurement in the software realm because they have adopted an approach similar to traditional infrastructure procurement with a narrow focus on lowest bids. This has empowered large, often multinational, software-as-a-service technology companies. These entities tactically approach public sector technology procurement opportunities with strategically low bids. Should they win, they try first to leverage existing software assets where possible. These assets are supplemented with piecemeal additions. The results have been less than desirable, leading to cost overruns, delays, products with gaping holes or various combinations of these challenges.

If the Government of Canada truly wants to procure modern technology to improve public services, it must first step back and examine its procurement processes.

Software specifically aimed at creating organizational efficiencies should be a highly iterative process that brings together both the developer and procurer. A minimal viable product (MVP) should be defined early in the procurement and off-the-shelf technologies or configurable software should be considered first, against the specific needs. If such straightforward solutions do not exist, flexibility in traditional procurement processes must be introduced. Access to internal users of a proposed technology solution should be provided early and often in the procurement process for all potential bidders. A selected company must continue to have access to end users through an “Agile” development process (Rigby, Sutherland and Takeuchi 2016) to learn, iterate and pivot as required. This approach is often referred to as a co-development approach in public sector technology development, in which risk and responsibility are co-managed.

The economics of such deals should also follow the same principles, whereby the vendor is incentivized to deliver toward the MVP incrementally. Under traditional procurement methods, vendors, especially those who underbid, are actually incentivized to fail in delivering the MVP on time as agencies have amended or expanded contracts with hopes of getting projects on track.

While the co-development approach is contrary to the government’s traditional approach to infrastructure and procurement generally, there is a need for two-way validation in the procurement of technology: both to define what success looks like, with a high degree of specificity, and to evaluate whether a potential bidding agency has the internal capability to deliver a working prototype.

This approach falls somewhere between traditional requests for proposals (RFPs) and requests for information (RFI) in government procurement terms. The RFI/RFP approaches, which allowed for separation between end users and suppliers, were set up to maintain transparency and accountability. These are two important features of Canadian public procurement and should be principles woven into any technology procurement program. However, this should not be to the detriment of the intended outcome. Interaction that allows for common understanding and iteration can embody transparency and accountability if government is willing to innovate in its procurement processes.

A Uniquely Canadian Approach to Balancing Prosperity and Efficiency

If the Government of Canada intends to both improve public services and drive long-term prosperity through technology, it will have to be clear about that dual purpose in developing and executing its technology infrastructure procurement.

The government already has a supply-side technology procurement program, known as the Build in Canada Innovation Program (BCIP) (Government of Canada 2017), managed by Public Services and Procurement Canada. This program is intended to support Canadian industry by allowing federal departments and agencies to utilize prototypes of Canadian companies’ technologies. This program has delivered minimal results in terms of sustainable economic growth of any magnitude, largely due to its design.

Companies wishing to access and utilize the BCIP must have a working prototype that has never been sold. Government departments and agencies can then purchase these prototypes and work with the Canadian company to commercialize the technology. While this late-stage development may be useful if the prototype meets the majority of the customer’s specific needs, it is a long way from a co-development approach.

In the 2017 budget, the government signalled an intention to create a demand-driven technology procurement program, modelled on the United States’ Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) (United States, n.d.) program. That program allows for public sector agencies to define their most pressing internal challenges and for small businesses in the United States to bid on solving these challenges through the co-development of technology solutions. Similar approaches have been adopted in other countries, such as Japan, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

While it seems the Government of Canada would like to separate its economic growth creation programming from its efforts to improve public services, the reality is the optimal policy prescription to achieve both mandates — public sector efficiencies and prosperity — sits squarely between the supply and demand approaches (see Figure 1 below).

The United States, unlike Canada, has a large and diverse technology sector that includes a robust small business sector of technology companies focused on public sector technologies. Demand pull under those circumstances can drive prosperity through the development of public-sector-focused technologies with US public sector entities across the service spectrum that can then be exported globally.

Canada, on the other hand, has a nascent technology industry. Firms specializing in public-sector-related technology also reduce the viable pool of companies that could both deliver government efficiency and create economy growth.

If the Government of Canada wants to maximize the efficiency it wishes to achieve through its investments in technology and see economic growth driven through the non-tangible assets it will have a hand in creating, it will have to take a uniquely Canadian approach: conducting independent exercises to define the greatest needs across the public sector and identifying emerging domestic technology companies that can drive tangible efficiencies in these areas.

A final and equally important litmus test should be utilized to shortlist projects: export potential. While Canada’s public sector is relatively large per capita, it will be impossible to drive prosperity, at a firm or national level, through domestic procurement alone. By focusing on technologies and companies that have the greatest export potential as a mitigating factor in a strategic procurement program, the Government of Canada could reduce its long-term costs to service such technologies and see a greater multiplier on its investments. The government could also serve as a reference customer and standard setter for these new technologies geared toward global public sector reform.

Figure 1: The Optimal Zone for a New Digital Infrastructure Procurement Program

Utilizing this approach would also protect the government from potential bilateral or multilateral trade disputes. The United States’ SBIR program is insulated from national treatment clauses in trade deals such as the North American Free Trade Agreement and at the World Trade Organization, as small business programming benefiting US firms was grandfathered into these agreements.

By focusing procurement of Canada’s new digital infrastructure on areas of need in which only small and medium-sized Canadian companies have the ability to deliver upon the specific outcome, the Government of Canada would remain in compliance with international trade obligations, as foreign firms would not explicitly be ruled out from participating. The Ontario government, via the Ontario Centres of Excellence, has taken this approach through its Small Business Innovation Challenge program (Ontario Centres of Excellence 2017).

Meaningful Challenges, Co-developed Solutions and Global Market Applications Need Impactful Investment

The Government of Canada has shown itself to be willing to buck conventional economic thinking by committing to a multi-billion-dollar stimulus program via infrastructure investments during this period of slowed economic growth. Spending on traditional infrastructure for spending’s sake, despite slowed demand for tangible goods, is not a viable economic strategy.

The Canadian government has a compelling opportunity to make strategic investments in technologies that address real public sector pain points and to co-develop with young and growing Canadian technology companies that have export potential. However, taking advantage of this opportunity will require meaningful investment and thoughtful program design. The government already spends CDN$5 billion on information technology (IT) and another CDN$3 billion annually on applications, devices and IT program management (Government of Canada 2016, Appendix B). Between these funds and the increased infrastructure spending, there is an opportunity to find funds to invest in technology that will drive better services, create internal efficiencies and grow Canadian companies of global magnitude.

With any investment that has a high return potential, there is greater risk. In evaluating such a program, the government should both take a portfolio approach, aiming to get more right than wrong, and instill patience in its evaluation process.

Getting a public sector technology infrastructure program right will require a strategic approach that challenges conventional thinking. That alone will not solve Canada’s economic challenge. However, the return for getting such a program right would be hardening Canada’s technology sector into global public sector supply chains that pay critical dividends in the form of growing Canadian-founded and operated technology companies that employ thousands with quality jobs for decades to come.