Elaine Herzberg was killed on the night of March 18, 2018, after she was struck by a self-driving Uber car in Tempe, Arizona. Herzberg was crossing the street with her bike when the vehicle, which was operating in its autonomous mode, failed to accurately classify her moving body as an object to be avoided. Rafaela Vasquez, a backup safety driver who was tasked with monitoring the self-driving car, did not see Herzberg crossing the street. Following the accident and Herzberg’s death, Uber resumed testing its vehicles on public roads nine months later, and subsequently has been cleared of all criminal wrongdoing. More than two years later, Vasquez, the safety driver of the purported autonomous vehicle, continues to face the prospect of vehicular manslaughter charges.

As more autonomous and artificial intelligence (AI) systems operate in our world, the need to address issues of responsibility and accountability has become clear. However, if the outcome of the Uber self-driving accident is a harbinger of what lies ahead, there is cause for concern. Is it an appropriate allocation of responsibility for Rafaela Vasquez alone — and neither Uber, the actor who developed and deployed the technology, nor the state of Arizona, which allowed the testing to be conducted in the first place — to be held accountable?

Both dynamics, human as backup and human as overseer, co-exist within a long history of automation that consistently overestimates the capacities and capabilities of what a machine can do.

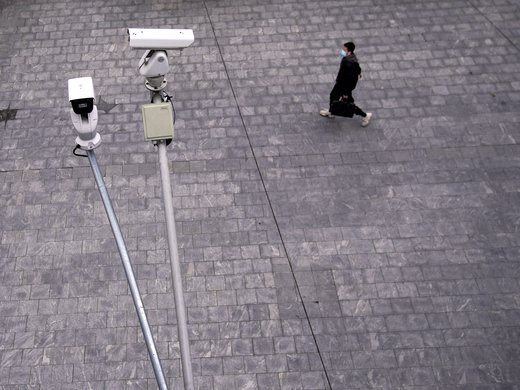

Notably, Vasquez was the “human in the loop,” whose role as backup driver was to ensure the safe functioning of the system, which, while autonomous, was not necessarily accurate 100 percent of the time. Such a role is increasingly common, in which humans are required to “smooth over the rough edges” of automated technologies. Scholars continue to document the myriad forms of human labour, from media platforms to online delivery services, that are required to keep intelligent systems operating “intelligently.”

At the same time, the principle of keeping a human in the loop is often called upon as a way to ensure safety and accountability, and to enhance human agency. For instance, the importance of human agency and oversight is a key theme in the European Union’s white paper on governing AI systems. Yet, both dynamics, human as backup and human as overseer, co-exist within a long history of automation that consistently overestimates the capacities and capabilities of what a machine can do — and underestimates the critical role of humans in making technologies work effectively in our world.

While human oversight is an important step toward ensuring that future AI systems enhance human dignity and fundamental rights, it isn’t a straightforward solution; it matters a great deal how that human is positioned “in the loop” and whether they are empowered — or disempowered — to act. Figuring out the right ways to design for and certify human-AI collaboration will be one of the major challenges facing the responsible innovation and governance of AI systems.

Many of these challenges aren’t new; there is much to be learned from the history of automation when it comes to anticipating the risks ahead. Consider, for instance, the safety-critical industry of aviation, which has been refining the dynamics of human-automation systems since the early twentieth century. What might we learn from examining some of this history? When my colleague and I began a research project on this topic, we were interested in understanding how conceptions of responsibility and liability in the American context had changed with the introduction of aviation autopilot, which we took as a kind of proto-autonomous system. We looked at the history of accidents involving aviation autopilot by reviewing court cases and the official government and news reports surrounding aviation accidents.

Through our analysis we noticed a consequential pattern: conceptions of legal liability and responsibility did not adequately keep pace with advances in technology. Legal scholars have, of course, pointed out the ways in which courts and politics tend to lag behind innovation, but our finding highlighted a particular consequence of that lag: while the control over flight increasingly shifted to automated systems, responsibility for the flight remained focused on the figure of the pilot. While automated systems were being relied on more, the nearest human operators were being blamed for the accidents and shortcomings of the purported “foolproof” technology. There was a significant mismatch between attributions of responsibility and how physical control over the system was actually distributed throughout a complex system, and across multiple actors in time and space.

We called this a moral crumple zone, as a way to call attention to the obscured — and at times unfair — distributions of control and responsibility at stake in complex and highly automated or autonomous systems. As we describe it in our paper, “Just as the crumple zone in a car is designed to absorb the force of impact in a crash, the human in a highly complex and automated system may become simply a component — accidentally or intentionally — that bears the brunt of the moral and legal responsibilities when the overall system malfunctions.”

The concept of a moral crumple zone is more than a fancy way to talk about a scapegoat. The term provides language to talk about potential harms and failure modes that may escape a regulatory eye. The term is meant to call attention to the particular ways in which responsibility for the failures of complex automated and autonomous systems (with distributed operations) are incorrectly attributed to a human operator, whose actual control is limited. In this way, the technological component remains faultless and unproblematic, while the human operator is isolated as the weak link. Unlike the crumple zone in a car, which is made to protect the human driver, the moral crumple zone reverses this dynamic, allowing the perception of a flawless technology to remain intact at the expense of the human operator.

Our research examined other historical instances of moral crumple zones, including the partial meltdown at Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in 1979 and an Airbus Air France crash in 2009. In each instance, there were common narratives and explanations that focused on human error and the failures of operator oversight. However, the nature of these failures takes on a different light when viewed in the context of technical systems’ limitations and decades of human factors research. For instance, in the case of the partial nuclear meltdown, while the control room operators were responsible for monitoring the plant operations, the control room display design didn’t adequately represent all of the physical conditions of the system; the human operators did not have — and could not ascertain — information about some of the failures happening elsewhere in the plant. (This accident has been extensively studied and was an important turning point in the development of complex information display and human factors systems design.) In the case of the Airbus crash, one of the fatal errors made by the pilots is most likely to have been caused by increasing reliance on automation. Both accidents underscore what Lisanne Bainbridge has called “the irony of automation”: in practice, automation does not eliminate human error — instead, it creates opportunities for new kinds of error.

The circumstances surrounding these accidents demonstrate how human oversight was ineffective because, in many senses, the human in the loop did not have meaningful control and was structurally disadvantaged in taking effective action. The responsibility for failures was deflected away from the automated parts of the system (and the humans, such as engineers, whose control is mediated through this automation) and placed on the immediate human operators, who possessed only limited knowledge and control.

Sadly, we also saw a moral crumple zone emerge in real time during the events surrounding the accident involving the self-driving Uber car, described earlier. As the first reported pedestrian fatality involving a driverless car, the accident garnered a lot of media attention. After the initial hours of reporting, the media narrative quickly changed from focusing on “the driverless car” to focusing on “the safety driver.” The story shifted from being about Uber and the safety of self-driving cars to being about a delinquent safety driver, Vasquez, who was slacking off on the job.

While there does appear to be evidence that Vasquez was looking at her phone right before the accident (she says she was monitoring the system dashboard), it is worthwhile to reflect on whether legal (as well as mass media narratives of) responsibility should fall primarily on her. The investigation conducted by the US National Transportation Safety Board revealed software and organizational shortcomings as well as hardware decisions made by Uber. Further, decades of research demonstrate the stubborn “handoff problem,” referring to the difficulty of transferring control of a system from machine to human quickly and safely.

Moral crumple zones do not always arise in the context of autonomous systems, but we would be wise to be on guard against their formation. The risk is that the “human in the loop” design principle becomes a way for system designers to — albeit inadvertently — deflect responsibility, rather than a way for humans to be empowered and retain some control. Accountability, in this case, is unfairly centred on only one component, which had only limited agency.

As we look to the future of AI governance, concepts such as the moral crumple zone and the socio-legal history of automation can help us anticipate some of the challenges ahead. If AI systems distribute control across space and time and among different actors, how can new modes of accountability address this complex distribution? Given that social perceptions about a technology’s capacities profoundly shape regulation of new technologies, should we ensure (and if so, how) that perceptions of technical capacities are as accurate as possible? Calling for human oversight is an important first step, but in itself is not enough to ensure the protection of human agency and dignity.

The concept of a moral crumple zone points toward not only legal but also ethical challenges when designing and regulating AI. It calls our attention to the growing class of workers who enable the functioning of automated and AI systems and facilitate their integration into the world, providing necessary monitoring, maintenance and repair. As the COVID-19 pandemic transforms our world, the people who make up this hidden human infrastructure have been revealed as both essential and yet also structurally vulnerable and precarious. It is imperative that so-termed “essential workers,” as Sujatha Gidla has written, do not become a euphemism for “sacrificial workers.” How should AI governance strategies protect those who work alongside AI systems? Policy proposals and systems design must focus on articulating the collaboration and hand-off points between humans and AI systems not as points of weakness, but as interactions to be supported and cultivated, and as seams to be exposed and elevated, rather than hidden.