Like many parents during the COVID-19 pandemic, I have spent the past month at home, with my son. We cancelled a larger family Christmas, Zoomed with grandparents and hunkered down at home. Having spent the better part of the past year living in rural British Columbia, we were well prepared. Over this period of isolation it has been remarkable to observe how our son has developed hobbies, like magic, sketching, Rubik’s Cubing and, most obsessively, origami.

Since these interests are definitively not hereditary, we first turned to books to feed his insatiable new curiosity. But the limits to this pedagogical approach quickly became apparent: his paper folding was considerably more advanced than his reading, which demanded a fair amount of supervision. In search of more self-directed instruction, we somewhat reluctantly turned to YouTube. And what we found was amazing.

It turns out there is a vast community of amateur origamists on YouTube. Our seven-year-old son emerged from tutorials with ever more intricately designed objects, repeating the dozens of folds by memory in front of his astonished parents. It really was remarkable. We found ourselves embracing, and, if I’m being honest, benefiting from, his screen time on YouTube. Surely this is better, we told ourselves, than the passive consumption of Netflix?

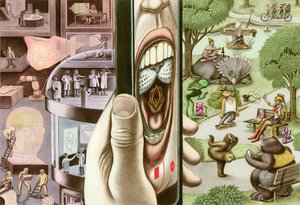

Then one day I found our son trying to hypnotize himself. It turns out that following a tutorial of a disappearing coin trick from a kids’ magic channel I had approved him watching, YouTube’s up-next algorithm recommended a video about self-hypnotism. When I shut it down in shock, he said, “But Dada, it will help me get the best sleep of my life!” Parent of the year.

There is considerable irony in this situation. I study digital technology and have for years spoken loudly and with increasing concern about the potential harms posed to our society, our democracy and, indeed, our children. YouTube, in particular, has a bad record. While platforms such as Facebook and Twitter have taken modest, if insufficient, steps toward addressing some of the more egregious harms caused by their products, YouTube’s response has been far more complacent. For example, while Facebook, and later Twitter, banned false claims of election victory after the 2020 US presidential election, YouTube let these damaging claims go viral. And in 2019, when the Canadian government required platforms to create a public archive of political ads during the federal election, Google, which owns the YouTube platform, simply pulled out of the political advertising market.

YouTube’s record is even thornier when it comes to kids’ content. On YouTube Kids (an age-restricted app designed specifically for children), violence against child characters, age-inappropriate sexualization and even recorded suicide attempts embedded in kids’ videos have been found by parents and journalists. Many of these videos have hundreds of millions of views. A recent controversy occurred when parents found popular kids’ shows being re-uploaded with spliced-in clips of a man joking about how to cut yourself. “Remember, kids,” he says in the video, “sideways for attention, longways for results.”

I strongly believe that better regulation is the solution to many of the challenges posed by digital platforms. The free market has provided an inadequate defence against the wide range of harms enabled by our poorly regulated digital infrastructure. However, the example of how kids use digital technologies presents an additional set of challenges. Should we only regulate the internet for adults, or do kids need additional protections?

I recently had the opportunity to talk to British filmmaker and online children’s rights advocate Baroness Beeban Kidron, who believes that our current age-indiscriminate approach to internet regulation ignores the rights that we grant children in other areas of the law. Following an illustrious film career (including directing Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason), Kidron was named to the House of Lords in 2012. A year later she directed the documentary InRealLife, which profiled the online lives of British teenagers. Since then, she has become a tireless advocate for better regulation of how platforms treat kids, most recently working through the House of Lords’ Democracy and Digital Technologies Committee to implement groundbreaking regulation called the Age Appropriate Design Code, which came into force in September 2020.

The code establishes 15 standards for how platforms must handle children using their services. These include higher default privacy settings; restrictions on the use of nudges such as autoplay, notifications and endless scrolling; bans on sharing of any data collected about children; the stipulation to quickly delete any data collected; and limits on the use of Global Positioning System tracking. And unlike platforms that define children as users under the age of 13, the new code includes all users under the age of 18.

These rules are important, and potentially radical, because they challenge the core underlying design and the business model of the platform internet itself. By attributing harm to algorithmic nudges, data collection and location tracking, British law makers are bringing attention to harms stemming from the way the platform internet functions. What’s more, if these features are being regulated because of their harm to children, surely it is fair to ask whether they should also be limited for adults.

As Baroness Kidron said of the code, “Children and their parents have long been left with all of the responsibility but no control. Meanwhile, the tech sector has, against all rationale, been left with all the control but no responsibility. The Code will change this.”

While much of the current discussion about platform regulation, in Canada and elsewhere, focuses on the symptoms of the problem, this code opens the door to a discussion about its root causes — the very design of our digital infrastructure. And given the real benefits that platforms such as YouTube can provide to children and adults alike, I hope governments will act to ensure that these platforms are safe for users of all ages.