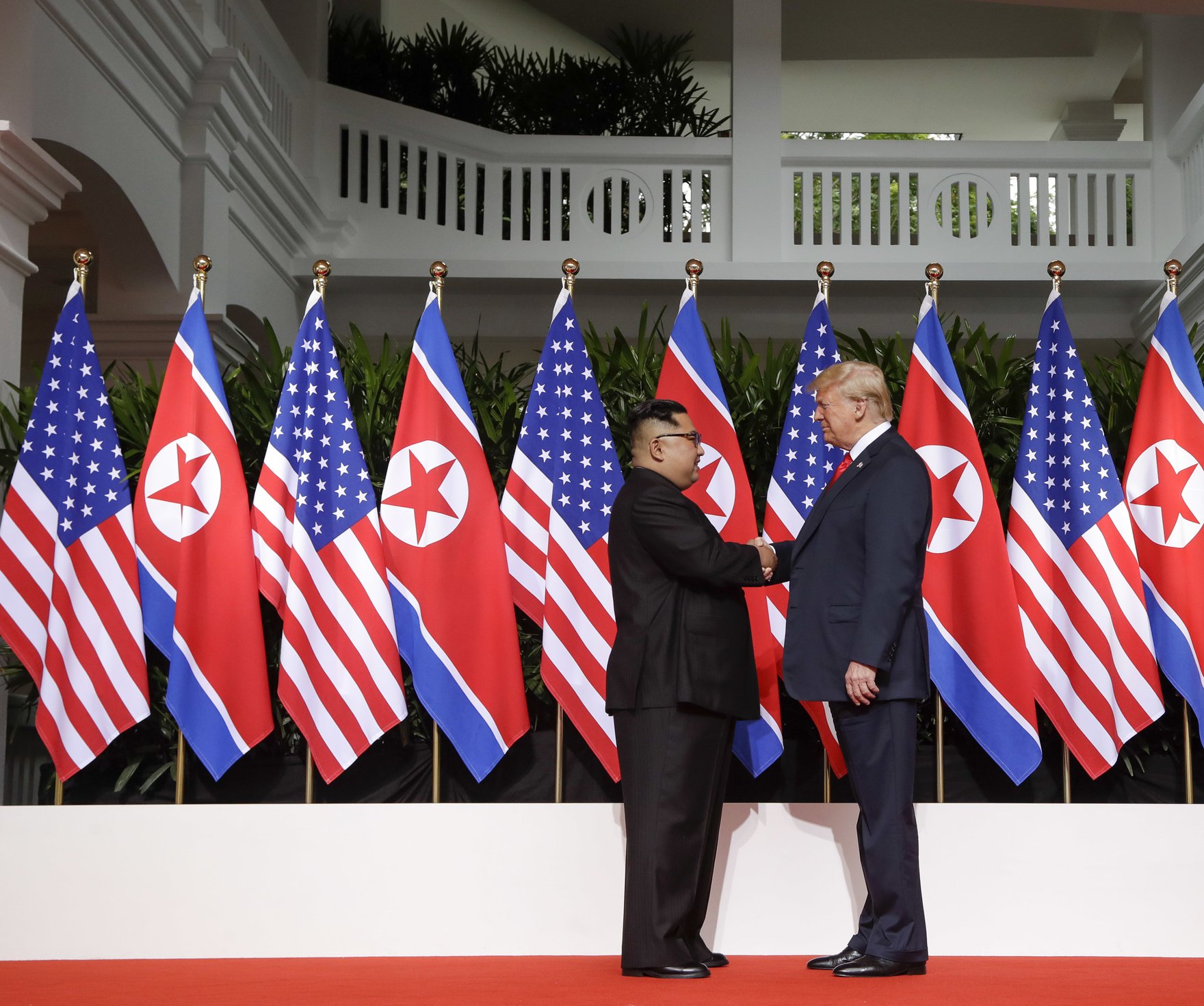

Assume, for a moment, that the sentiments that Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump expressed in Singapore on June 12 are genuine. What would need to be done to make those aspirations real?

The Singapore Joint Statement, of course, contains four principal clauses: efforts to establish a new relationship that fosters peace and prosperity; efforts to “build a lasting and stable peace regime on the Korean Peninsula”; a recommitment by North Korea to the Panmunjom Declaration, which calls for “complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula”; and an effort to recover remains of US prisoners of war and fallen soldiers from the Korean War.

While the first three clauses in particular are broad — arguably, so broad that they could be trivially easy to satisfy — they do point to very real policy goals that both the United States and North Korea have held for decades. Still, a long list of obstacles could derail even the sincerest efforts to eliminate North Korea’s nuclear weapons program and to develop a comprehensive peace treaty for the Korean Peninsula.

Four specific issues — in no particular order — need to be addressed to turn the Singapore summit into something more.

Sequencing

The Singapore document contains, on the one hand, three big, long-standing, North Korean demands: normalized diplomatic relations; normalized economic relations/economic aid; and an iron-clad security guarantee from the United States. The United States, on the other hand, has one overriding demand of North Korea: dismantle your nuclear weapons arsenal and infrastructure.

How to sequence the series of concessions that each side would have to make is a daunting question with no right answer. North Korea has already rejected the idea of repeating the Libyan experience, where Muammar Gaddafi’s government handed over its nuclear infrastructure and chemical weapons first, with the United States and others delivering most of their promises in return. Failure to agree on sequencing could stall negotiations before they even get going.

The problem of how to sequence talks and concessions also raises a related “time inconsistency” problem, which is a fancy way of saying either party could walk back their concessions in the future. For example, if North Korea shuts down a uranium centrifuge plant to please the United States, it may decide to reopen it in the future. This is one of the reasons that the United States wants North Korea not just to suspend or freeze its nuclear activities, but to irreversibly destroy or convert its nuclear facilities. North Korea faces a similar problem with the United States. Today, Washington may wish to sign a solemn legal pledge to never take aggressive action against North Korea (as the United States and Russia did when Ukraine got rid of its nuclear weapons in 1994), but North Korea needs to have some way of making sure that if the United States changes its policy (as Russia did with Ukraine), Pyongyang can respond.

If both countries are serious about achieving the Singapore goals, agreeing on sequencing will be a critical early task. Failing to do so would, at best, delay the process. At worst, failure to establish sequencing would stop talks in their tracks.

Who’s in the Room?

A peace treaty between North Korea and the United Streets is one thing, but a comprehensive treaty that ends the Korean War and legally normalizes relations between North Korea and South Korea will require, at a minimum, Chinese and South Korean participation and, most likely, input from the rest of the coalition that fought under the United Nations banner from 1950 to 1953.

More broadly, most long-term plans to get rid of North Korea’s nuclear weapons while simultaneously guaranteeing its security will require other countries to play a role.

How will the North Koreans guard against the possibility that the Americans, willing to make peace today, might become hostile in the future? China may need to extend a security guarantee to Pyongyang (as the United States does to Seoul today). If North Korea demands investment capital to rebuild its withered economy, who will provide it? South Korea is one obvious source. The United Nations Security Council will need to be involved in removing sanctions from the North Korean economy. The United Kingdom, France and, in particular, Russia (which borders North Korea) could easily make the case that they need to be at the table to ensure that any agreement is compatible with Security Council resolutions. It’s not likely that any of these countries would cede all responsibilities to the United States. The Japanese government would also be wise to insist that they be part of any talks, given Tokyo’s troubled history with Pyongyang and the Japanese public’s concern about North Korea’s missile arsenal.

While the United States and North Korea made headlines in Singapore, the two will not likely be able to come to a durable arrangement on their own. Other countries will need to do some of the heavy lifting, and there will undoubtedly be a major role for the International Atomic Energy Agency to play in long-term monitoring and enforcement of the nuclear provisions of any agreement. The United States would do well to begin the process of assembling a negotiation coalition now, rather than later.

Separate Deals or a Grand Bargain?

Since the Singapore document covers several logically linked but distinct issues, North Korean and US leaders must also decide whether to address everything in one negotiation process or to try several specialized negotiation tracks, each dealing with a separate issue.

To put it very simply, the United States should prefer separate talks on nuclear weapons and a peace treaty, since it has much more to trade to North Korea (sanctions relief, economic aid and security guarantees) than North Korea has to trade in return. North Korea has two big bargaining chips: its intermediate and intercontinental ballistic missile program, and its nuclear weapons program. Its tradable options quickly tail off from there. Of course, North Korea does have the ability to raise tensions (via missile and nuclear tests, conventional military provocations and cyber attacks), which gives it some short-term bargaining power; North Korea could promise to de-escalate in return for concessions. But acquiring these sorts of tradable assets is a gamble: namely because the United States may decide to escalate in return.

Thus, Pyongyang’s best strategy is to insist that nothing is settled until everything is settled. A reduction in (or total abandonment of) North Korea’s nuclear weapons program will only happen as part of a package that includes security guarantees, normalized relations and economic aid.

Clarity on how to link (or separate) the issues won’t come until there’s some sense of how to sequence the talks and who else is going to be involved. But before any of that that can be done, the United States needs to be clear about one thing: what, exactly, President Trump committed to on June 12.

The “Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula”

This is the elephant in the room. Trump accepted North Korea’s preferred language of “denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula” rather than specifying the unilateral, complete, verifiable and irreversible dismantling of Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal. The definition of “denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula” is still the subject of debate.

Past documents, such as the 1992 Joint Declaration of the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, the 1994 Agreed Framework and the 2005 Joint Statement of the Fourth Round of the Six-Party Talks mention the term in conjunction with prohibitions on the United States’ use of nuclear weapons against North Korea and with the understanding that North Korea will still have the right to have a civilian nuclear program.

As Pyongyang understands the concept, denuclearizing the Korean peninsula imposes obligations on the United States, too. Pyongyang’s understanding of what “denuclearization of the Korean peninsula” means leads us to the interim conclusion that any substantive effort to achieve denuclearization will necessarily entail changes to US policy. Perhaps inadvertently, Trump may have implicitly accepted some obligations for the United States when he signed the Singapore document. It’s unclear if the American president understands this, or if he can convince Congress — which gets to weigh in if the White House has a treaty arrangement with North Korea in mind — to go along. Senator Lindsey Graham made it clear that there is at least one policy line that Trump probably shouldn’t bother trying to cross: trading an American troop withdrawal from South Korea for movement on North Korea’s nuclear program. Graham is no doubt speaking for a majority of senators.

If there’s any one issue that could decisively halt any and all diplomatic progress between the United States and North Korea, this is it.

If the Singapore summit was a genuine and serious effort at inching North Korea closer to freezing, curtailing and eventually dismantling its nuclear weapons program through a negotiated solution, then the White House must make sure it knows what American negotiators can credibly promise.

Conclusion

If you want to wager on what comes next between North Korea and the United States, a return to “fire and fury” or “nothing” are safer bets than “structured arms control negotiations.” The aforementioned issues are but a select few that Washington will have to deal with — ideally, swiftly — if there are going to be serious talks between the United States and North Korea. Some of those issues — in particular, sequencing and the meaning of “denuclearization” — might not have nice, clean solutions.

Singapore made headlines, and maybe history, but there are plenty of reasons why the summit between the United States and North Korea might end up amounting to very little.