Last month, US Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer released a bipartisan “Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence Policy,” developed after months of high-profile forums, listening sessions, and discussions with experts and stakeholders.

The road map lays the foundation for forthcoming artificial intelligence (AI) legislation, addressing issues such as innovation, workforce impacts, high-impact applications, election integrity, privacy and liability, transparency and explainability, intellectual property, AI risk and national security.

Having lobbied for months for light-touch regulation and increased federal spending, tech companies welcomed the document and the pledge of US$32 billion in taxpayer money for AI innovation. But scholars and advocates who participated were disappointed.

For one thing, the road map failed to robustly address AI risks and harms. While the framework briefly mentions concerns such as civil rights protection, bias mitigation, accountability and trust, it emphasizes a tech-driven innovation narrative. This approach aligns more with tech companies’ interests than with those advocating for a responsible AI ecosystem.

In response, advocates have drafted a shadow report to guide meaningful legislative efforts in the public interest, underlining the need to place public at the forefront of AI policy making. Among its highlights are 11 critical areas for AI regulation, including racial justice, AI accountability, labour rights, competition and privacy, and a call for immediate legislative action to implement enforceable regulations that prioritize the public interest over industry self-regulation.

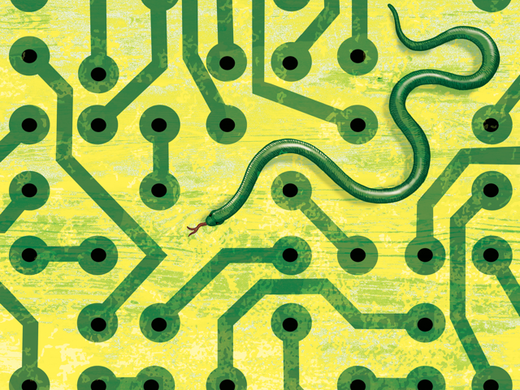

In reality, there is no definitive answer to how AI should be regulated. Global efforts range from meaningful regulation to light-touch approaches or mere lip service. Tech companies tend to capture both policy forums’ and law makers’ hearts and minds with their well-established innovation narrative. This long-standing and contested innovation-versus-regulation debate significantly shapes AI policy discussions, not only in the United States but also globally. Indeed, this narrative was successfully used to water down the EU AI Act in the name of promoting innovation in Europe.

The innovation argument is not new. Various sectors have relied on it in the past: the auto industry lobbying against safety regulations, the chemical industry against health and safety rules, and social media companies against efforts to protect privacy and data. It’s a familiar tactic — like a genie in Aladdin’s lamp, invoked to push back against regulation.

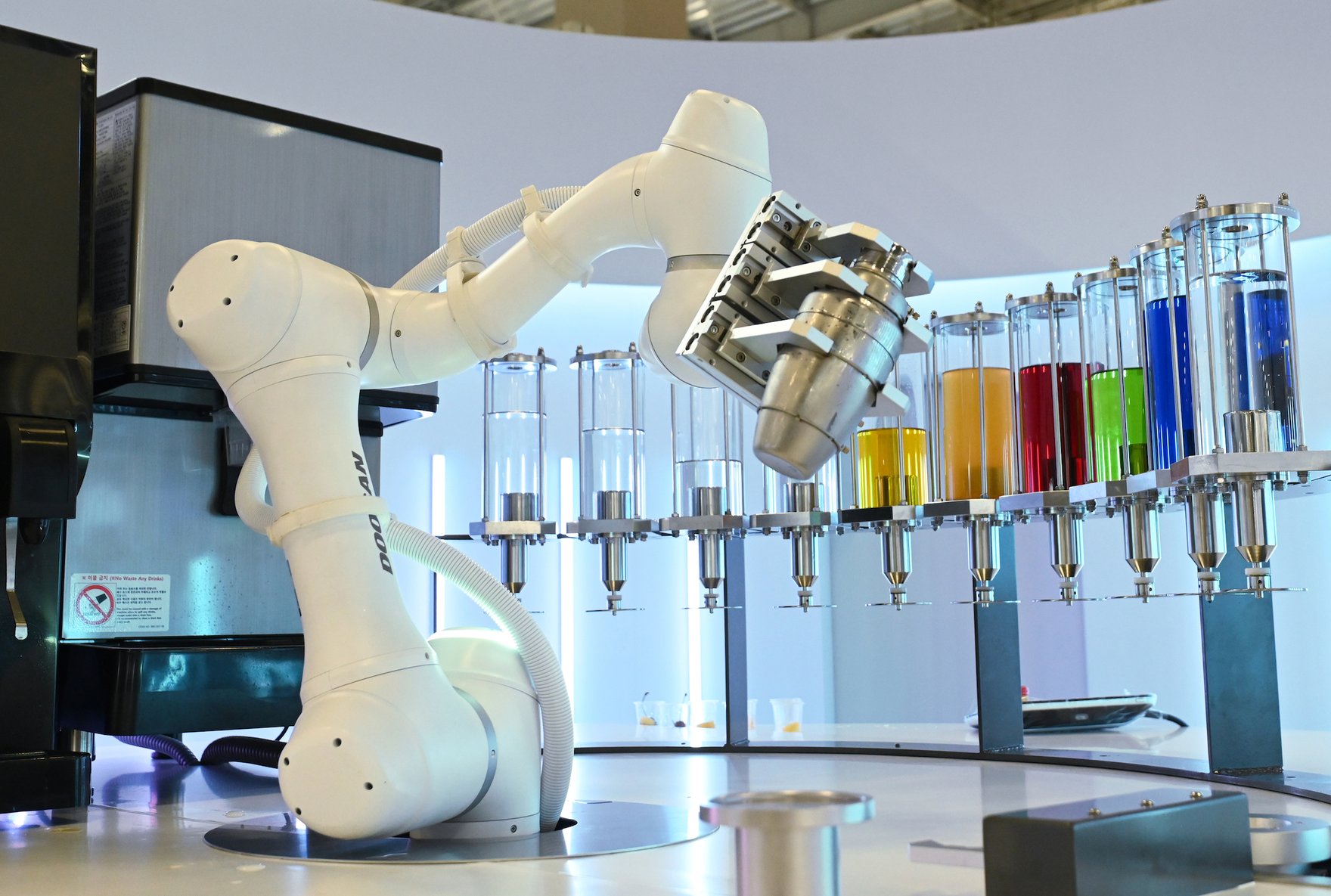

This raises an important question: Innovation for whom? Tech companies argue that we could all live in a world in which AI simplifies our lives by automating tasks and providing personalized information and recommendations. If law makers could only view policy from the individual consumer’s perspective, understand the utilitarian benefits of AI, invest more in research and development, and allow the market to regulate itself, the world would become more innovative, efficient and consumer-friendly, according to this line of thinking.

Historically, tech and labour policies have been developed in isolation, guided by distinct objectives and regulatory frameworks.

But in the last few years, the United States has shifted its policy focus from prioritizing consumers — a narrative often aligned with corporate interests — to emphasizing citizens’ well-being, including that of workers, farmers, small businesses and communities.

The Biden administration continues to redefine its approach to the digital economy with a “worker-centered” strategy. This shift is evident in both antitrust and trade policies, recognizing the monopoly power of tech companies. It acknowledges that policies benefiting people as consumers should not undermine them as workers.

Historically, tech and labour policies have been developed in isolation, guided by distinct objectives and regulatory frameworks. This lack of coordination has resulted in a trickle-down approach that shaped the digital economy and the mindset of policy makers. Tech policies were crafted from a consumer-welfare perspective, emphasizing the utilitarian benefits of market monopolization, automation, rampant data collection and advertising, and executed in ways that support surveillance capitalism.

But the effects of any technology — whether it is accessible, equitable or harmful — depend on who controls the crucial decisions about its development and sets the agenda. While AI is relatively new, it can be viewed through the lens of previous significant innovations such as the printing press, steam engine, electricity and the internet.

In the current debate around AI, voices are growing louder against the primacy of automation, surveillance and runaway technology. A new approach that prioritizes workers’ interests — placing them above those of shareholders, companies and consumers — may yet emerge. And it should.

We need to change our traditional approach to policy making, which typically relies on industry and government experts to draft sector-specific and tech-friendly policies, followed by periods of public feedback that have little impact.

We have repeatedly seen innovation-friendly loopholes within these legislative proposals that would make it too easy for companies to self-regulate and avoid accountability. These loopholes are then replicated across multiple legislative initiatives. It’s clear that AI policy development could benefit from a truly inclusive approach. We cannot count on the social responsibility of a few tech companies that hold great power and control over our futures.

Last year, the high-profile strikes by the Writers Guild of America and by the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, which represents performers and broadcasters in Hollywood, highlighted the challenges workers face with AI technologies and their impact on creativity and creators’ livelihoods. The unions and studios eventually reached an agreement that includes protections for writers’ work and gives actors control over their images. These strikes demonstrated the power of collective bargaining, not only for securing better wages and workplace protections, but also for shaping AI development. This is the major lesson of that experience.

The “worker-centered” policy approach aims to develop the digital economy from the bottom up and the middle out, placing workers at the heart of policy making. It supports equitable and just policies, and fosters competition, sustainable development and fair-trade practices worldwide, not only in America but also in the Global South.

Similarly, a worker-centric AI policy approach would empower workers, democratize AI benefits, minimize risks, and promote equality, stability and prosperity. By bringing workers from all backgrounds and experiences to the table, we can create an inclusive AI policy that advances economic security and racial and gender equity.

It is crucial that those who have been systematically excluded or overlooked — such as women, communities of colour, low-skilled workers and the Global South — have a strong voice in global policy discussions.

Industrialization brought people together in factories, fostering new aspirations and counterbalancing forces for democratizing its benefits, leading to significant technological changes and institutional development for shared prosperity. As Frederick Douglass said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” Progress and justice are not freely given by those in power, but rather achieved through organized efforts, demands for change, and collective action. By placing workers at the heart of AI policy development, we can ensure a more equitable, just and prosperous future for all.