In Hans Christian Andersen’s famous folk tale, a vain emperor is persuaded that the latest thing in wearable tech is invisible cloth, but that only very clever people can see it. As the artists set up their invisible looms, bureaucrats and nobles gather around marvelling at the complex texture of the fabric, no one wanting to admit that there is nothing there. Only when the emperor parades proudly through the streets, dressed in his new clothes, does a child point out that he is naked.

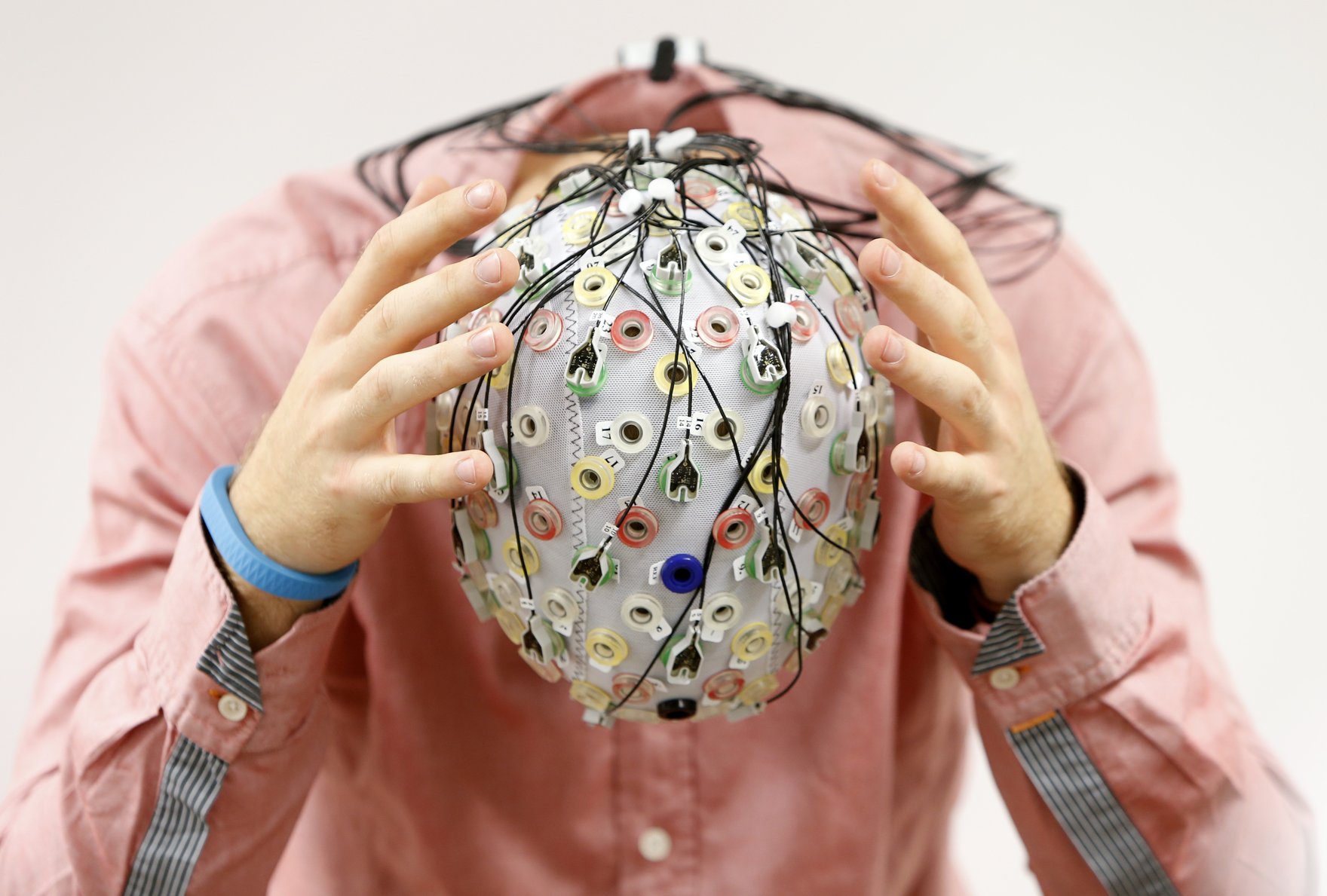

If you follow the news, you will know that in tech there is a good market for invisible clothes that only the highly intelligent can see. Perhaps the epitome of this is anything that has “neuro” tagged on to it. “Neurotech” is the term coined for technology that engages with our brains. Some experts claim this deserves new rights, or “neurorights,” to manage the implications for humanity. No one wants to be seen as a fool in the face of tech innovation.

On July 13, UNESCO convened an international conference on the ethics of neurotechnology and in June, the United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) released a report on neurotechnology which warned of the risks of our “neurodata” being used against us.

This is undoubtedly an important new field that regulators will need to grapple with, but what is sometimes more worrying than the tech itself is the lack of legal rigour applied to policy discussions about it. The challenge when blinded by the latest shiny thing is not to lose sight of existing laws we should apply to it.

The UK Human Rights Act is 25 years old this year. It is an important legal protection which governs the way public authorities must respect our human rights. What this means is that the ICO has to apply data protection law and regulation, including on neurotechnology, in a way that respects existing human rights. Along with the Equality Act of 2010, it is a key part of the country’s legal framework, yet it does not even feature as a footnote in the ICO’s analysis of the laws applying to neurotech.

Instead, the report focuses on a campaign for new “neurorights” and, insofar as it mentions existing rights at all, gets them wrong. The ICO has a technology advisory panel of which I was a member. But, never having had the opportunity to actually advise, I resigned last month because I could not stand behind such a deeply flawed report. The campaign for neurorights does not have general support among human rights experts. And given these issues are very serious, we cannot afford to have our regulators investing heavily in imaginary legal cloth.

Benjamin Franklin wrote that “without freedom of thought, there can be no such thing as wisdom.” Calls for new rights to be formalized in the United States, where there is no constitutional right to freedom of thought, might make sense. But in countries such as the United Kingdom, or member states of the European Union, where applicable domestic and international human rights laws do guarantee the absolute right to freedom of thought, it is a potentially dangerous distraction from the protection we already have.

The campaign for “neurorights” often gives the false impression that existing rights do not apply. But as the former UN special rapporteur, Professor Ahmed Shaheed, put it, the right to freedom of thought “stands ready to rise to the complex challenges of the twenty-first century and beyond.” We don’t need new rights, we need access to justice and strong regulators who know the law and apply it.

Freedom of thought will be key to neurotechnology’s future, both to define the legal and ethical limits of its use, and to guarantee the freedom to innovate. Instead of weaving invisible neurorights, we need to make use of the legal fabric we have to protect rights today, and in the future.

This article first appeared in the Financial Times.