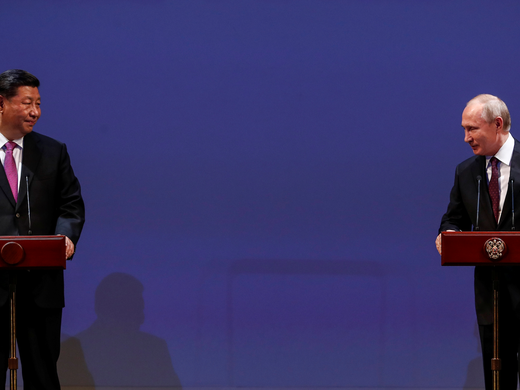

President Joe Biden and President Xi Jinping gave reassuring statements after their meeting at the Group of Twenty leaders’ summit in Bali in November, yet one month earlier, the grand political set piece that was the twentieth national congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) stoked new fears over Taiwan’s future. President Xi appointed hard-line acolytes to top party roles and delegates cemented denial of Taiwan’s independence into the CCP’s constitution.

In late December the US government authorized US$10 billion in spending over the next five years for Taiwan’s security needs, to which Beijing responded by ordering a record number of its military aircraft to violate Taiwanese airspace. Taipei also tripled the length of island’s mandatory military service, from four months to one year.

Despite the Thucydides Trap unfolding between an ascendent China and the United States — a declining global hegemon — armed showdown over Taiwan is not inevitable. Nonetheless, war games are now being used to produce an insightful, if incomplete, understanding of how such a devastating scenario might play out.

American military officials predict Taiwan may become a flashpoint between the two superpowers by 2027 or as early as this year — although most experts consider the latter timeline unlikely. Australia’s former prime minister Kevin Rudd, a fluent Mandarin speaker and leading Western sinologist, argues that changing internal CCP dynamics point instead to likely confrontation in the 2030s. However, Rudd offers a caveat, saying the chances of an accidental war breaking out this decade are rising, fast.

It’s an open debate among experts whether China could successfully annex Taiwan, an autonomous liberal democracy of more than 23 million people that Beijing views as a renegade Chinese province. Additional uncertainty comes because of the seeming parallels here to Vladimir Putin’s catastrophic gamble in Ukraine. President Xi, a notoriously paranoid leader, surely understands that China’s massive and technologically advanced military is unproven in open conflict. An invasion of Taiwan risks becoming a Putin-style humiliation for him and the CCP.

And yet brinkmanship between the two superpowers is escalating. Chinese fighter jets breach Taiwan’s air defence zone almost daily, with total military flights around Taiwan numbering more than 1,700 in 2022 — double the previous high. Outgoing US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s provocative visit to Taiwan last August elicited intense live-fire drills and a practice blockade of the island by the Chinese Navy. The Biden administration in October severed Chinese access to US semiconductor technology. US export restrictions may soon cover the strategic realms of quantum computing and artificial intelligence as well, an overt threat to Xi’s vision for Chinese high-tech self-sufficiency.

Since 2018, the US Air Force has run several classified simulations of a Chinese attack on Taiwan, predicated on a hypothetical 2030 conflict. The first two iterations in 2018 and 2019 suggested a dominating win for China. A third version, in 2020, saw Chinese gains confined to one area of Taiwan. However, this only came about in the model due to a notional expansion of American air power across the region involving military technology that does not yet exist — next-generation autonomous attack drones and a theoretical “mesh network” of cheaper, lightweight drone defence units blanketing the island and its surrounding waters in a three-dimensional aerial grid.

These simulations indicate defending Taiwan would require deploying a decentralized network of US military teams throughout the theatre of combat. In these simulations, each team is comprised of up to 30 personnel in total, with members from each US military branch — Air Force, Army, Marines, Navy and Space Force — who could all be linked in real time by portable devices akin to electronic tablets. This would necessitate further developing the US military’s Joint All-Domain Command and Control capability — a conceptual automated information technology system that can securely relay live information between different service branches, which are still mostly siloed off from each other.

American think tanks have recently run their own exercises. Last June, the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) released a report on war gaming a Chinese attack on Taiwan, set in 2027. Among its findings were that “there is no quick victory for either side if China decides to invade Taiwan” and that the consequences of the attack would spiral far beyond what Beijing and Washington could ever anticipate. Then, in August, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) ran a series of closed-door simulations of a US-China conflict over Taiwan in 2026 that encompassed two dozen different iterations, with the full report's release expected in early January.

Participants in the CSIS exercise assumed China would launch crippling cyberattacks against Taiwan in the opening hours of an invasion. But preparing for China’s cyberattack capability is nothing new. Taiwan’s government is already planning to spend millions of dollars over the next two years to upgrade its mobile and 5G (fifth-generation) mobile network base stations and protect its undersea internet cables. Fourteen of these cables provide linkages to surrounding nations and global networks — a “serious Achilles’ heel” for the island, Kenny Huang, CEO of the state-backed Taiwan Network Information Center, told Bloomberg.

However, in response to these war games, Beijing-friendly voices seemed to exude confidence in China’s prospects for taking Taiwan, in part because of the growing electronic warfare capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Taiwan has witnessed how high morale, careful planning, good leadership and social solidarity confer advantages to a smaller defensive force in asymmetric warfare.

One commentary from the Institute for China-American Studies (ICAS) — a Chinese-funded think tank based in Washington, DC, known for supporting China’s aggressive territorial claims in the South China Sea — said the CNAS and CSIS war game scenarios were “likely more entertaining than they were accurate and constructive.” Its analysis argued their methodologies overemphasized orthodox weaponry despite how “after a decade of modernization that prioritized high-tech electronic warfare … it would be more efficient for China to use its [electronic warfare] units … [than to] dramatically wipe out …Taiwan’s defense capabilities.”

The ICAS commentary cites the electronic warfare tools of the PLA’s Eastern Theater Command — land-based stations on Hainan Island near Vietnam, and others allegedly dotted along China’s eastern coastline, as well as air-based platforms, including planes and drones.

It goes on to say: “Should China adopt the less violent but more capable [electronic warfare] approach in this 21st century context, can U.S. policymakers rally enough public support without loss of life?” This hints at what Beijing may have gleaned from the surprisingly resilient Western reaction to Russia’s macabre tactics in Ukraine — killing civilians and reducing towns and cities to ashes galvanize resistance against aggressors. Implicit here is recognition of how, again much as in Ukraine, Taiwan’s creative, open society would likely win the digital propaganda war against dogmatic CCP narratives.

Taiwan’s military remains vastly outgunned and underprepared to square off with Chinese forces anytime soon. Yet veteran New York Times national security correspondent David Sanger recently pointed out that China may be underestimating the complex, self-inflicted ramifications stemming from an attack knocking out — even briefly — Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, which produces over 90 percent of the world’s most advanced microchips.

Also not captured within the war games are the unpredictable ways in which Taiwanese society would mobilize to protect its sovereignty and identity from being annihilated. For example, retired Taiwanese tech billionaire, Robert Tsao — who was born in China — recently announced plans to spend US$100 million to kick-start a consortium to produce one million low-cost attack drones and to train and arm a civilian defence militia of three million people by the mid-2020s.

Taiwan has witnessed how high morale, careful planning, good leadership and social solidarity confer advantages to a smaller defensive force in asymmetric warfare; this has arguably been the most important force multiplier for Ukraine in repelling what on paper is overwhelming Russian firepower. Plus, as many experts have pointed out, electronic warfare has its limits — especially if the objective is to capture and hold territory.

This indicates why war games will never provide a definitive answer to what could occur if China and the United States were to clash over Taiwan. And that isn’t really the point. Researchers from the Virginia-based think tank CNA Corporation, which designs war games for the US Department of Defense, advised in a piece for Foreign Policy in April 2022 that war games are but a tool to “explore and understand a complex problem, regardless of the outcome.” In essence, they are just a “plausible method of providing a brief and limited glimpse into a possible future — a single future in a multiverse of possibilities.”

Therefore, the best result is always the one in which the outcomes predicted, including those that might affect Taiwan’s fate, can be wholly prevented in the first place.