Six months before Black Tuesday, the Wall Street Crash of 1929, two German philosophers met to debate in a Swiss town that was trying to make a name for itself as a center for intellectual tourism, Davos. The previous year Einstein had lectured there and played violin to entertain visitors.

The philosophical protagonists were Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger. Underpinning the abstractions of their argument was a fundamental question: was technology elevating humanity, or destroying it?

Cassirer was an idealist, fascinated by the challenges of modernity. What did Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity mean for the theory of knowledge? What were the philosophical implications of quantum mechanics? And yet in grappling with these problems, he also confronted the possibility that physicists and mathematicians, not philosophers, were better placed to answer them or advance beyond them.

Heidegger thought modern life was rubbish.

He saw technology and rationality as soulless and dehumanizing. His philosophy placed human beings in the middle of blood, soil and action. But his anti-intellectualism and nationalist mythology also made philosophy redundant. A world peopled by Heidegger’s heroes would have little time for thinking and place little value in it.

In Davos, under the very technical constraints in which they debated, Heidegger won and Cassirer lost. Heidegger’s victory symbolised the crisis of liberal intellectuals. They lost philosophically, they would go on to lose politically.

In 1933, Heidegger, already an admirer of Adolf Hitler, became a member of the Nazi party.

That same year Cassirer, German, but from a family of Polish Jews, fled his professorship in Hamburg to spend the rest of his life abroad.

Nationalist nihilism triumphed intellectually over cosmopolitan idealism.

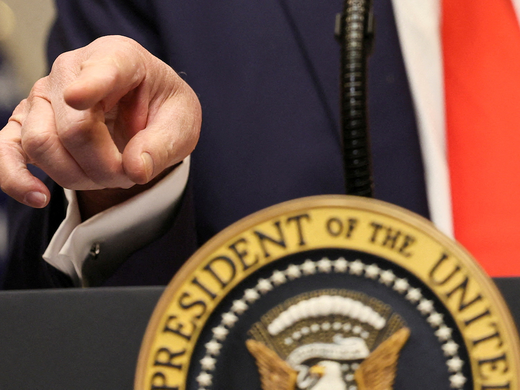

Today I work for an organization that brings people together in Davos: the World Economic Forum. There are professors there, but there are also business leaders and politicians and more. The language is less academic but the questions remain. Is technology our friend or foe? Are we rootless cosmopolitans or planted in nationalism? Are we people of action or of words?

Today’s intellectual crisis of confidence is not over philosophy but globalization. And the future that has western economies wondering is not Germany’s but America’s.

That future is captured starkly in this review of Samuel Huntington’s Who Are We?:

Three possible American futures beckoned, Huntington said: cosmopolitan, imperial and national. In the first, the world remakes America, and globalisation and multiculturalism trump national identity. In the second, America remakes the world: Unchallenged by a rival superpower, America would attempt to reshape the world according to its values, taking to other shores its democratic norms and aspirations. In the third, America remains America: It resists the blandishments — and falseness — of cosmopolitanism, and reins in the imperial impulse. Huntington made no secret of his own preference: an American nationalism "devoted to the preservation and enhancement of those qualities that have defined America since its founding." His stark sense of realism had no patience for the globalism of the Clinton era. The culture of "Davos Man" — named for the watering hole of the global elite — was disconnected from the call of home and hearth and national soil.

Huntington’s myth was the American dream.

It was only for the white, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant: "There is no Americano dream. There is only the American dream created by an Anglo-Protestant society. Mexican-Americans will share in that dream and in that society only if they dream in English."

The Huntingtons and the Heideggers are once more in the ascendant.

A year before his death, in 1944, Ernst Cassirer wrote an explanation of what he thought had happened to Germany in The Myth of the State:

In politics we are always living on volcanic soil. We must be prepared for abrupt convulsions and eruptions. In all critical moments in man’s social life, the rational forces that resist the rise of the old mythical conceptions are no longer sure of themselves. In these moments the time for myth has come again. For myth has not been really vanquished and subjugated. It is always there, lurking in the dark and awaiting its hour and opportunity. The hour comes as soon as the other binding forces of man’s social life, for one reason or another, lose their strength and are no longer able to combat the demonic mythical powers.

He did not survive the war. Heidegger did.

Adrian Monck is head of public engagement and foundations, and a member of the managing board of the World Economic Forum

This article is published in partnership with the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2017