The US Federal Reserve is a boys’ club again.

In February 2018, Jerome Powell, the former private-equity investor who has served on the Fed’s Board of Governors since 2012, took over from Janet Yellen as chair.

Powell is well regarded; 84 senators supported his nomination, while only 13 opposed. By comparison, Yellen was confirmed in 2014 after a 56-26 vote.

Nonetheless, Powell’s appointment weakens the Fed. United States monetary policy once again will be determined almost entirely by a group of older white men. Yellen could have continued to serve as a member of the board, but she opted to resign after President Donald Trump decided not to reappoint her. From 2011 to 2013, there were three women on the board. Now there is one, Lael Brainard.

Diversity matters. Men and women provide different perspectives, which is important when deliberating economic policy.

Yellen’s departure will leave four vacant positions on the Fed’s seven-member Board of Governors, and there is little reason to think any of them will be filled by women. Trump’s list of potential central bankers appears to be almost entirely composed of men. Before Powell, Trump named Randal Quarles to fill the new position of vice chairman in charge of banking supervision. He also nominated Marvin Goodfriend, an economics professor at Carnegie Mellon University, to fill one of those vacancies on the board. So far, only one woman — Michelle Bowman, who leads Kansas’s financial services regulator — has made it into the media gossip about who Trump might next nominate to fill a Fed seat.

All of this suggests the policy-making culture at the Fed could change, and not in a good way.

Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan is an impressive economist, but the cult of personality that he inspired during his tenure constrained debate, leading to policy mistakes that contributed to the financial crisis.

Greenspan’s successor, Ben Bernanke, sought more input from his colleagues to foster a richer dialogue and avoid groupthink. It also helped that during Bernanke’s second term as chair, he could rely on a strong cohort of women on the board who could contribute different perspectives to the policy debate. One of those women was Yellen, who joined the board as vice-chair in 2010; she succeeded Bernanke and became the first woman to lead a major central bank.

Yellen merited a second nomination.

When she took office in early 2014, the worst effects of the Great Recession had passed and it was evident to everyone that the time had come to resume the tightening of monetary policy.

Yellen’s biggest challenge was to get the timing and the pace of those increases right — no small feat.

There is an art to monetary policy. it takes about two years for an interest-rate change to affect economic conditions, so central bankers always are looking ahead: increasing interest rates too quickly could squash a recovery, but waiting too long could fuel high rates of inflation. Economic data is imprecise and often backward-looking.

Yellen faced an additional challenge: the economics profession had become unsure of its models, as they had failed to predict the financial crisis, and economic conditions were unique in that the recovery was not being reflected through wage growth or inflationary pressures. Post-crisis policy making therefore required a great deal of judgement.

During Yellen’s first year as chair, the unemployment rate fell much quicker than projected. That prompted suggestions that the Fed was losing its grip on inflation.

Yellen had a different view; she argued that further monetary accommodation was needed to recover from the damage of the Great Recession. Despite pressure to raise interest rates faster by financial market participants, central bank watchers and politicians, Yellen stood by her conviction that the true state of the labour market required deep analysis of a broad range of economic indicators, not just the unemployment rate.

She was right.

Initial forecasts suggested interest rates would increase by three percentage points during Yellen’s four-year term; instead, they have increased by less than half that amount. The economy is now strong, long-term unemployment has decreased by over 50 percent and labour force participation has stabilized, while inflation is on target. The US Fed is now fulfilling its dual mandate of full employment and price stability for the first time in a decade.

Simply put, Yellen restored the Fed’s credibility. She did so by getting the policy right, and by improving the central bank’s dialogue with the public.

During her time in Washington, Yellen championed changes to the Fed’s communication strategy, and she took further steps to stamp out the notion that the Fed is a cult of personality. Yellen delivered just under one-third of the speeches by members of the Board of Governors, a change from Bernanke, who delivered more than half of the Board’s speeches during his tenure. This change supports the idea that the diversity of views of Fed policy makers is important and shifting attention from a single leader — or a celebrity central banker — to the institution, where policy is set by a group of qualified experts.

The Fed succeeded in fighting the financial crisis in part because Yellen and a few other women on the board — Brainard, Sarah Bloom Raskin and Elizabeth Duke — brought ideas to the table that might not have entered the debate otherwise. Yellen championed women’s issues in economics, such as pay equality, gender balance across industries and occupations, and family issues. She also delivered speeches that aimed to connect economic and financial policy making with their socio-economic implications, such as for low-income households and inequality. These are key tenets of feminist economics, which aims to make the field of economics more cognizant of the social implications of economic activity, policies, analysis and theory.

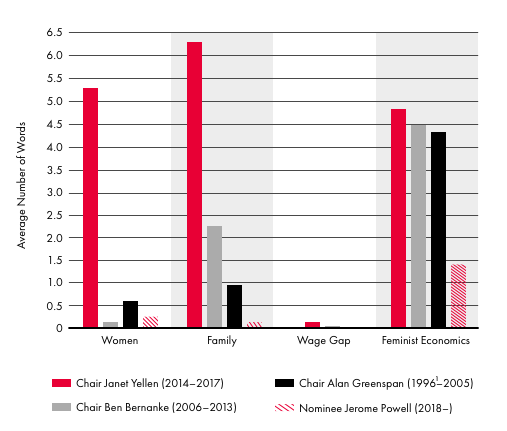

Figure 1 shows the average word count of terms related to women, family, wage gap and feminist economics per speech delivered by recent Fed chairs. Yellen has clearly taken stronger account of issues that affect women and families than her predecessors.

Yellen’s speeches show that the institution’s economic analysis is not restricted to headline values of inflation and unemployment, but also considers broader economic activity as it relates to people’s experiences. Perhaps most importantly, Yellen has demonstrated that this perspective is complementary to achieving the central bank’s mandate.

Figure 1: Average Word Count per Speech by Theme and Chair

An analysis of all speeches delivered since 1996 reveals that women on the Board of Governors use feminist terms, on average, almost nine times per speech, nearly double that of their male counterparts. Brainard has a relatively high use of these terms and will provide an important balance on the committee going forward. Quarles is viewed as friendly to Wall Street, so he will probably appeal to the financiers whom the central bank looks to for securing its credibility, but he is an unlikely champion of socio-economic considerations.

Powell uses terms related to the feminist economics relatively infrequently. Champions of this perspective will likely need to be sought elsewhere on the board.

Unfortunately, the Fed, as well as the broader economics profession, suffers from a lack of gender diversity. Yellen is the first female leader of a central bank in the Group of Seven economies, and women only make up 14 percent of monetary policy decision makers in these countries.

Janet Yellen helped strengthen the Fed’s reputation as an institution whose expertise in economic analysis and policy making is among the world’s finest. She reinforced the perspective that there is strength in diversity at the Fed.

The torch has been passed to Powell, but without the right people on his leadership team — women, in particular — he’ll struggle to uphold Yellen’s important legacy.