In July 2015, the Islamic Republic of Iran, along with China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States and the European Union, signed on to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), an agreement in which Iran would put substantial and verifiable limits on its nuclear science and engineering activities in exchange for sanctions relief. Many observers hailed the agreement as an important — if imperfect — tool for keeping Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. Former US President Barack Obama argued that “the United States, our partners, and the world are more secure because of the JCPOA.”

It barely needs to be said that in the United States there was — and is — no shortage of criticism of the agreement. Congressional Republicans and Democrats alike expressed opposition both during JCPOA negotiations and afterwards. Bob Corker, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman, argued that the JCPOA would “embolden the world’s leading state sponsor of terror while diminishing our leverage to stop them.” US President Donald Trump has, of course, referred to it as “the worst deal ever.”

While the agreement has eight signatories, two countries — Iran and the United States — have the most at stake. For Iran, the JCPOA lifted financial and trade sanctions that had been imposed on them by the United Nations, the United States and Europe, and that helped fuel an annual inflation rate of over 20 percent and helped cause the Iranian economy to shrink by nearly six percent from 2012 to 2015 (the Iranian economy grew nearly five percent annually over the previous 12 years). For the United States, it put a verifiable — if temporary — cap on Iran’s nuclear science and engineering activities, and thus Iran’s ability to build a nuclear weapon.

While the JCPOA is not a treaty, US law requires the American president to certify every 90 days that Iran is complying with its JCPOA obligations, and that continuing to waive sanctions against Iran is “vital to the national security interests of the United States.” As expected, Trump — without explicitly finding that Iran is not complying with the JCPOA — refused on October 13 to certify that abiding by the agreement continues to be in America’s interest. Trump further threatened that if Congress (and America’s allies) cannot offer an improved version of the JCPOA (which Tehran would presumably accept), then the United States will withdraw from the agreement. This would mean the wholesale resumption of sanctions.

Now that Trump has decided to decertify, Congress faces the choice of whether to reimpose sanctions on Iran.

Determining what effects Trump’s decertification will have requires a close look at the details of the alleged plan. There are three important aspects of the rumoured decertification plan: one procedural and two substantive. As Trump made clear, the White House’s decertification plan is an attempt to coerce Iran into making wholesale changes to its foreign policy.

Decertification, but Not Withdrawal

First, the procedural element: Decertification in and of itself does not mean that the United States automatically withdraws from the deal. It is important to note that Trump refused to certify that continuing to waive sanctions is proportionate to Iran’s behaviour and in the United States’ national interest, and that he did not make any substantive claim that Iran is violating the letter of the JCPOA. (Although, as Trump noted, Iran has on two occasions breached the limits of its heavy water stockpiles, in both cases those breaches were considered trivial. They did not substantively increase Iran’s ability to build a nuclear weapon and were quickly remedied.) The president has essentially handed the matter to Congress, with the message that the agreement, as written, is not in America’s interest: Rewrite it with America’s allies, or we’ll cancel it.

The Trump administration is essentially playing a coercion game with Tehran. Decertifying without withdrawing is betting that the Iranian government finds the promised economic pain of new financial and trade sanctions fearful enough, and the threat of withdrawal credible enough, to adjust its overall foreign policy behaviour to avoid those outcomes.

There are at least two reasons that the Trump administration’s effort to change Iran’s foreign policy behaviour could fail. The first is that the pain that the United States is threatening to inflict may be insufficient to cause wholesale change in Iranian foreign policy. If the threatened economic pain is lacking — compared to what Iran would have to give up to avoid that pain — then the gambit fails. The second problem is that the sanctions threat may not be credible, for example, because Iran believes Trump is bluffing, or because congressional hawks do not have the votes to pass a sanctions bill.

Is the White House’s Threat Effective?

It is by no means clear that Iran will reengineer its entire foreign policy to avoid financial and trade sanctions. It’s important to understand that the motive for decertifying Iran is not because Iran is violating the JCPOA — for the most part, it is sticking to the agreement. Instead, the argument is that Iran’s overall foreign policy behaviour is aggressive and dangerous for the Middle East. It sponsors Hezbollah and other terrorist groups. It is trying to politically dominate Iraq and Syria and turn them into puppet states. It threatens the region’s only democracy (Israel) and the United States’ Arab allies. It continues to develop and test sophisticated missiles and other conventional weapons. Tehran’s overall strategic policy goal is military and political pre-eminence in the Middle East and Persian Gulf. Iran’s neo-imperialist foreign policy is so intolerable to the United States that it would be worth risking a resumption of Iran’s nuclear activities if it means the United States can impose punishing trade and financial sanctions.

The problem is that the promise to cripple Iran with sanctions underlines the logic of Tehran’s imperialist foreign policy. The last 70 years have taught Iran’s policy makers some harsh lessons. From the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in 1941 (despite Iran’s official neutrality), to the United States-backed overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953 (which ushered in 25 years of autocratic rule by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi), to Iraq’s invasion of southeastern Iran in 1979 (a war in which Iraqi forces used chemical weapons on Iranian troops while the world remained silent), the twentieth century taught today’s Iranian leaders that it is better to be strong than weak.

This is not to defend Iran’s foreign policy. Far from it. Iran is visiting upon Iraq, Syria and other parts of the Middle East that which foreign powers imposed on it: foreign interference in domestic affairs. However, an all-out effort by the United States to cripple the Iranian economy and thus precipitate regime change bolsters Iranian conservatives who argue that the world is a hostile place and the United States an implacable and untrustworthy foe. It is easier for Iranian hawks to make the policy case that it is worth suffering economic deprivation to acquire a nuclear arsenal — which could then guarantee Iran’s physical security and aid in its quest to dominate its near-abroad — so long as it appears that a foreign power plans to visit economic ruin on the country when it is not building nuclear arms. Iran pursues its foreign policy out of self-interest. Since Iranian national security policy makers see political and military pre-eminence in the Middle East as a sure way to preserve their regime and to prevent the humiliations and disasters of the twentieth century, we have to question whether they would automatically give up those efforts to avoid another round of economic warfare with the United States. The conclusion that Tehran would obviously not risk economic pain for dominance in Iraq, Syria and beyond is far from unassailable.

Is the White House’s Threat Credible?

The second element of the plan is the assumption that the JCPOA would be simple to rewrite or that crippling trade and financial sanctions can be easily reimposed (and enforced) on Iran; in other words, that the threat is credible. Again, we should seriously question this assumption. One memorandum, which allegedly has been circulated within the White House and on Capitol Hill, asserts that the notion that the pre-2016 global sanctions regime was the result of long-term diplomatic efforts by the United States is a “myth.” Instead, according to the memorandum, once the US Congress imposed sanctions, the world complied. According to this logic, implementing and then effectively enforcing regime-crippling sanctions will be a simple task, as no firm or country will risk access to the US banking system so that they can trade with Iran.

Will the rest of the world jump if the US Congress snaps its fingers? Proponents of decertification certainly have some facts on their side here. The US dollar is still the world’s reserve currency, and access to the US banking system is crucial for companies that import to (or export from) the United States, and is useful for firms that do business in US dollars (many commodities are priced around the world in US dollars).

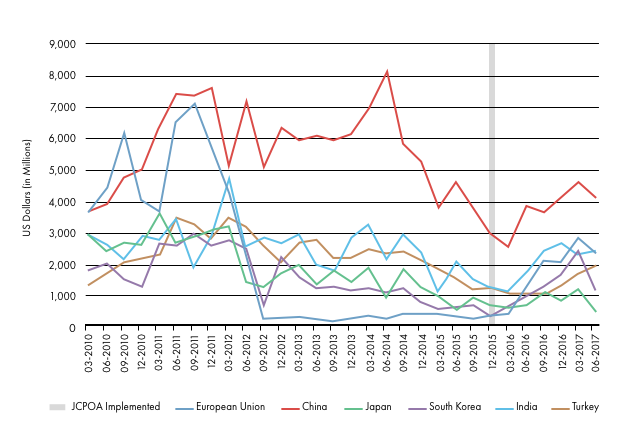

There are a couple of reasons to temper that optimism, though. While Iranian exports are not at the levels they were before the global sanctions coalition came together in 2010–2012, they have begun to recover. Even US aerospace giant Boeing has entered the Iranian market, inking deals to sell US$20 billion worth of civilian aircraft to Iranian airlines. Governments and firms will be more resistant to cutting commercial ties now that they’ve been resumed (Figure 1).

The European Union may also invoke what is known as blocking regulation, which protects EU citizens and firms from extraterritorial applications of law by third countries. In this case, the European Union — especially if it concludes that Iran is abiding by the JCPOA — could decide to ignore US sanctions and prevent European firms from abiding by them.

Figure 1: Iranian Exports to Select Markets

While multinational firms are right to worry about the long arm of the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, it is by no means a sure bet that America’s allies and adversaries will comply with its demands.

It is also far from clear that Congress is willing or able to write a new sanctions bill or revise the JCPOA right now. Even legislators who are skeptical of the JCPOA, such as Democrats Chris Coons and Eliot Engel, argue that as long as Iran complies with the deal, the United States should stick with it. Ed Royce, the Republican chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, said: “As flawed as the deal is, I believe we must now enforce the hell out of it.” If Democrats (and Independents) vote according to the party line in the Senate to not impose sanctions, they would only need to tempt three Republicans to join them. Given the president’s relationship with Congress and the administration’s handling of another nuclear weapons file (North Korea), finding three Republicans to vote with the Democrats would be doable.

Finally, America’s allies (some of which are full-fledged parties to the JCPOA) do not want to see the deal gutted and are in no mood to reopen it. British Prime Minister Theresa May has said the deal should remain “carefully monitored and properly enforced.” Her Conservative colleague and the former UK foreign secretary, William Hague, has been more blunt, arguing that if Trump breaks the JCPOA, “it will reinforce the idea that the word of America cannot be trusted.” Reports also suggest French President Emmanuel Macron is supportive of the agreement, and the United Kingdom, France and Germany have jointly reiterated their commitment to the JCPOA as is, and bluntly described preserving it as “in our shared national security interest.” In response to Trump, EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Federica Mogherini has been explicit, arguing that the JCPOA “is not a bilateral agreement, it does not belong to any single country and it is not up to any single country to terminate it.”

Among the messages that allies are trying to send to the White House is that there is also no contradiction between upholding the JCPOA and working to change Iran’s other foreign policy behaviour. Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland said as much on Friday when she laid out Ottawa’s response to the White House’s decision: more money for the International Atomic Energy Agency (which is responsible for monitoring Iran’s nuclear science and power programs) while denouncing Tehran’s behaviour in Syria, its support for terrorist organizations, its threats to Israel and its ballistic missile tests.

Last, but certainly not least, there is also no indication that the other parties to the agreement — Russia and China — are interested in revising the deal. If America’s allies are cool to Washington’s new policy, adversaries are using even stronger language, with the Kremlin warning that if the United States were to withdraw, it would “damage…predictability, security, stability, and [nuclear] non-proliferation worldwide.”

How much of the rhetoric coming from the rest of the world reflects genuine fears about the consequences of decertifying Iran and to what extent it is simple posturing is unknown. However, by publicly staking their positions in opposition to the White House, governments are now on the record, and will have to at least work to moderate the United States’ Iran policy, lest they damage their own credibility. From Tehran, this likely looks like a signal that it will not be a simple task for Washington to reassemble the pre-JCPOA sanctions coalition.

Note that this analysis does not delve into how Iran might retaliate to decertification, or whether it can evade and stymie US sanctions efforts. Any full assessment of any threat or promise by the White House to decertify Iran (or the JCPOA) would have to take those factors into account.

No Time for Magical Thinking

The White House’s approach to Iran’s aggressive foreign policy and the JCPOA is an example of making perfect the enemy of the good. It is simple — on paper — to point out the JCPOA’s flaws, and to argue that not only is achieving a better deal possible, but easy too.

This is simply not true. The JCPOA is a flawed but useful agreement. It is the result of years of sanctions and negotiations that were aimed at getting Iran to agree to aggressive international monitoring of its nuclear science and engineering programs. That process has worked so far. The world is watching Iran’s nuclear activities as closely as one can reasonably hope. So long as there is no evidence that Iran is preparing to break out of the agreement and sprint toward a nuclear weapon, there is no reason to tempt fate and undermine the deal.

The idea that Iran can cheaply — and easily — be brought to its knees with a blunt, impulsive and simple threat is seductive but naive. Magical thinking is not going to resolve the decades-old conflict between Washington and Tehran.