The recognition that the modern economy is increasingly driven by data and online commerce has led to a number of initiatives to establish a global data governance regime that promises “data free flow with trust” or DFFT, and an associated open e-commerce regime. Since then, notwithstanding progress in formulating proposals to build the trust that is the key to enabling free flow, international frictions have pushed in the opposite direction and today’s reality is closer to unfree flow with no trust than it is to DFFT. The issues go beyond the technical and legal frameworks required to build trust at the level of private participants in the digital economy — the household/consumer and corporations. They extend to the geoeconomics and geopolitics of the knowledge-based and data-driven economy that emerge from the contest for the rising economic rents that this economy generates and the parallel contest for leadership/dominance of the new general-purpose and dual-use technologies built on the nexus of big data/machine learning/artificial intelligence (AI). This note discusses how data and digital trade policies are shaped by the new geoeconomics and geopolitics and how these strategic plays are in fact endogenous to the technological conditions of the age.

Introduction

The recognition that the modern economy is increasingly driven by data and online commerce has led to a concerted push to establish global regimes for data governance and e-commerce. For example, the Group of Twenty (G20) adopted the goal of “data free flow with trust” in response to the ambitious exhortation by Japan’s then Prime Minister Shinjo Abe who said in a speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2019, “I would like Osaka G20 to be long remembered as the summit that started worldwide data governance” (Abe 2019). The World Trade Organization (WTO) negotiations toward an e-commerce regime were also launched at Davos that year with a nod to the G20 process (European Commission 2019). And in May 2019, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore announced the launch of negotiations to a new Digital Economic Partnership Agreement (Joint Ministerial Statement 2019). The latter was concluded in short order, albeit with little progress over what had already been achieved in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (Fay and Ciuriak 2021).

Various policy papers have sketched out how the global regime for data and digital trade might be further elaborated (e.g., Chen et al. 2019; Cory, Atkinson and Castro 2019; World Economic Forum 2020; Casalini, López-González and Nemoto 2021; Aaronson et al. 2021). Others have emphasized stumbling blocks on the path to the Osaka vision: treatment of data as a national asset (e.g., Greenleaf 2019); fundamental differences in national views on the governance of data (e.g., Lancieri 2019); and the problem of valuation of data flows, since there is no explicit accounting of the value of data as a commercial asset (Ciuriak 2019a).

Overall, notwithstanding progress in formulating proposals to build trust, international frictions have pushed in the opposite direction. Today’s reality is closer to “unfree flow with no trust” than it is to DFFT — consider, for example, European distrust of US surveillance, China’s elaboration of new data privacy and security laws with stringent cross-border clearance requirements for “sensitive” data, US restrictions on Chinese digital firms on national security grounds, India’s exclusion of Chinese apps, Russia’s national internet, and so on (Cory and Dascoli 2021).

The issues go beyond the technical/legal frameworks required to build trust for private participants in the digital economy — the household/consumer and corporations. They extend to the geoeconomics of the knowledge-based and data-driven economy, which emerges from the contest for the economic rents that this economy generates, and the superimposed geopolitical contest for leadership/dominance of the new general purpose and dual-use technologies built on the nexus of big data/machine learning/AI.

This note discusses how data and digital trade policies are shaped by the geoeconomics and geopolitics of the modern data-driven economy. As background, the second section considers how the prevailing technological conditions shape the economic characteristics of an age, and how these characteristics in turn determine the extent to which nations are likely to leave the allocation of production and trade to rules-based governance versus engaging in strategic behaviour. In that light, it also sketches out the economic and technological facts of the data-driven economy. The third section draws out the endogenous geoeconomic and geopolitical reactions given these economic and technological conditions. The fourth section discusses the implications for a rules-based e-commerce system and the associated regime for data flows.

Background: Technological Conditions and the Rules-Based System

It is important to take a step back and look at how technological conditions shape economic conditions, which in turn drive endogenous responses by firms and states, and what this means for a rules-based order.

The mature industrial era (pre-1980) featured constant returns to scale and stability of the shares of national income flowing to capital and labour (the so-called “Kaldor facts”; Kaldor 1961).

- These conditions imply competitive market conditions and by extension only a limited presence of economic rents.

- Under competitive market conditions, markets allocate production and market share efficiently and indeed fairly.

- Under the principle of comparative advantage, all nations find their niche and share in the benefits through trade.

- In the absence of rents, it is convenient for nations to allow commercial disputes to be settled by legal principles.

A number of technological changes in the 1970s and 1980s, including importantly the introduction of the IBM personal computer in 1981, which enabled the industrialization of research and development through computer-aided design and manufacturing, gave rise to the knowledge-based economy circa 1980. Other technological/regulatory developments, including the introduction of the wide-body Boeing 747 with a design based on capability for cargo transport and the facilitation of including intermodal logistics, enabled geographically distributed production — which Richard Baldwin has described as the “second unbundling” (Baldwin 2016).

This economy featured increasing returns, a growing internationalization of production through global value chains, and a business model based on protection of intellectual property. The Kaldor facts were no more — we saw a rising profit share of GDP, a falling labour share and a skewing of income distribution toward the one percent. We also saw the emergence of strategic trade policies to capture the growing economic rents, including major prolonged confrontation over strategic areas such as dynamic random-access memories and civilian aircraft. The WTO was designed in and for this age with a major objective of containing strategic behaviour. It came into being about halfway through the knowledge-based economy era, which can be dated from 1980–2010.

If we fast-forward to 2010, the world emerging from the global financial crisis is being transformed by new technologies developed in late 2000s:

- the development in 2006 of deep-learning techniques based on stacked neural nets by Geoffrey Hinton at the University of Toronto (Kelly 2014);

- the introduction by Apple of the iPhone in 2007, which launched the age of mobile and sent soaring the amount of data continuously accumulated and streamed into the now rapidly expanding cloud (Molla 2017); and

- the application by Andrew Ng and his team at Stanford in 2009 of graphics processing units — computer chips designed for the massively parallel processing requirements of video games — to run stacked neural nets (Kelly 2014).

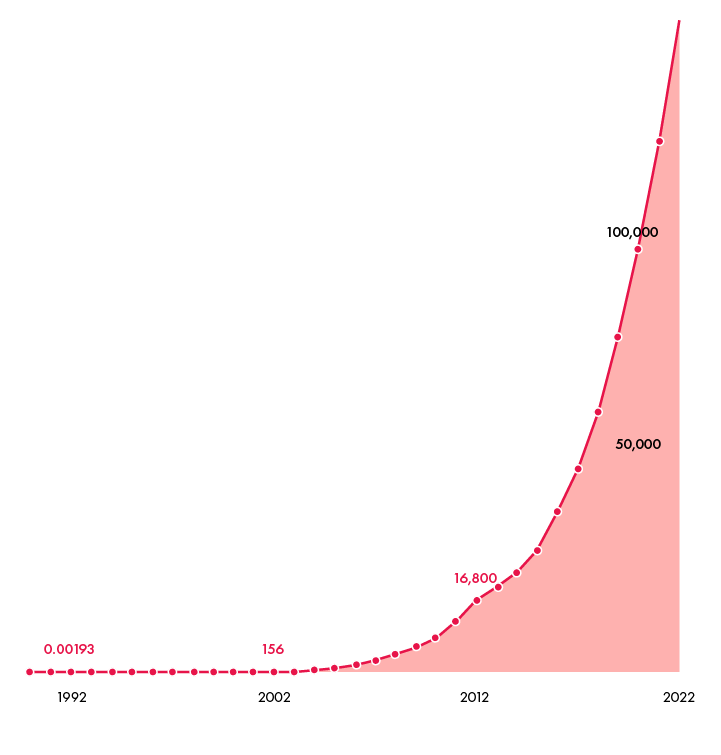

The “hockey stick” upturn in internet traffic and resulting data capture dates to about 2010. That year, Google’s Eric Schmidt (2010) announced the arrival of a new age, describing it as the age of mobile — mobile computing and mobile data networks. In reality, it was the age of technologies built on the nexus of big data, machine learning and AI — the data-driven economy.

Figure 1: Growth in Internet Traffic, 1992–2022 (projected), Gigabytes per Second

This new economy is prone to market failure because of economies of scale, economies of scope, network externalities in many use cases and irreducible information asymmetries (Ciuriak 2018). It also features steep growth of intangible assets, much of which consist of the value of data (although the exact share is difficult to ascertain since data is captured rather than being acquired in commercial transactions with a paper trail of invoices and receipts; Ciuriak 2019a).

With the market capitalization of the S&P 500 index at close to $40 trillion (Yardeni, Abbott and Quintana 2021), and an estimated share of intangibles at about 90 percent (Ocean Tomo 2020), we can infer that the value of intangible assets comprised as much as $36 trillion of the S&P 500 companies’ assets in 2021.

The past is only prologue: for our services-intensive economies, the introduction of massively scalable “machine knowledge capital” will be opening up sector after sector for strategic competition. Here it is salient to mention an aspect of the economics of data that has drawn little attention. The data-driven economy emerged in a services-intensive economy that is subject to the “Baumol effect” (Baumol 1967; Baumol, Batey Blackman and Wolff 1985). This refers to a stylized fact of economic growth that the transition into a services-intensive economy historically was associated with a marked growth slowdown (hence the oft-voiced concerns in developing countries about deindustrialization).

In a nutshell, post-industrial economies feature a rising share of services in GDP and, at the same time, experience a rise in relative costs of services. One reason for this effect is that services are much harder to scale than manufacturing.

Datafication changes everything for services-intensive economies because it introduces a highly scalable by-product of services that functions as a key factor input into the production of massively scalable AI (which has effectively a zero marginal cost of production). Human knowledge capital is not scalable; machine knowledge capital is (Ciuriak 2018). Scalability introduces rents and strategic behaviour is then inevitably induced.

The data-driven economy is not, therefore, an economy easily governed by a rules-based order — countries with economic power will not leave market shares and value capture of this magnitude to be determined by rules or arbitration panels. In addition, given dual-use features of the new general-purpose technologies built on the nexus of big data/machine learning/AI, we also have new geostrategic considerations coming into play.

The outbreak of the trade and technology war was thus in a sense preordained — and the disciplines crafted for the knowledge-based economy era to rein in strategic behaviour were quickly overwhelmed. It has been oft remarked that we are in second “gilded age” (Krugman 2014). The gilding is worth fighting over. Enter geoeconomics and geopolitics.

The Geoeconomics and Geopolitics of the Data-Driven Economy

Geoeconomics and Geopolitics in the Data-Driven Economy: An Identification Problem

Strategic behaviour in international relations can be broadly parsed out into two forms: geoeconomics and geopolitics.

The term “geoeconomics” is used in a number of senses (Schneider-Petsinger 2016). One sense is the use of economic power for non-economic objectives. Examples include China using access to its markets to silence criticism of its domestic policies (Zhong and Deb 2021) and the United States using its effective control over the SWIFT interbank clearing system to enforce compliance with its foreign policy on companies outside its formal jurisdiction (The Economist 2019; Simon et al. 2020). Another sense is the use of economic power to achieve economic objectives. Examples include the United States using access to its markets to leverage “rebalancing” concessions from Canada and Mexico in the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement and China using access to its market to leverage favourable terms for technology transfer.

Geopolitics involves strategic behaviour that is usually associated with political aims such as national security or national prestige; however, it can also include use of political and military leverage for economic benefits. In the early industrial era, this was commonplace — for example, the Opium Wars to open up the Chinese market to European and American traders on favourable terms to the latter. More subtly, when then US presidential candidate Joe Biden said, “NATO is not a protection racket” in differentiating his approach to that institution from the Trump administration’s (quoted in Caputo and Korecki 2019), he intimated something that is not normally said out loud. As the saying goes, when they say it’s not about the money, it’s about the money.

In the data-driven economy, there is a potentially toxic blending of geoeconomics and geopolitics in trade and investment policy. Technological superiority underpinned the strategic capabilities that established US hegemony in the unipolar moment that preceded the rise of China (see, for example, Eaglen and Pollack 2012; White House 2017, 20). Today, the nexus of big data/machine learning/AI is central to technology-based strategic competition: for example, AI in military applications is well advanced, including in fighter aircraft, weaponized drone swarms and AI-assisted exoskeletons for soldiers (see, for example, Ciuriak 2021a). Economic leadership in this critical technological area is thus seen as central to national security. The Biden White House’s interim national security guidance has stated: “economic security is national security” (White House 2021a, 15); there is discussion of aligning economic relations along political lines through “ally-shoring” (for example, Dezenski and Austin 2021) and of the formation of an economic club of “like-minded” democracies or a D-10 to counter “authoritarian economies” (China and Russia) to coordinate the buildout of 5G networks (for example, Fishman and Mohandas 2020; Wintour 2020). For its part, the European Union has adopted “strategic autonomy” and “digital sovereignty” objectives (Michel 2020). And China has adopted a “dual circulation” concept, which is interpreted as about “properly handling the relationship between openness and independence” (Sutter and Sutherland 2021).

This overlap between geoeconomics and geopolitics creates an identification problem that should be of more than a little concern to trade policy. National security claims are inherently dangerous for trade disciplines. Once national security is invoked in economic matters, the wheels tend to come off a rules-based system.

For example, justiciability of national security claims is disputed. In the WTO proceedings in Russia—Measures Concerning Traffic in Transit (Russia—Transit), the panel asserted the national security exception was justiciable and issued a ruling (WTO 2019); the United States, however, argued that “the text and negotiating history of GATT [General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade] 1994 Article XXI, as well as its place within the broader WTO framework, indicate that this provision is non-justiciable. That is, the text leaves its invocation to the judgment of a Member through the phrase ‘that it considers essential’” (United States Trade Representative 2018). For a discussion of how problematic this is, see, for example, Heath (2020a and 2020b).

As well, the normal rules of evidence are likely to be thrown out the window. In Russia—Transit, Russia presented its case in the hypothetical: “when asked by the Panel how closely the hypothetical situation described above reflected the actual situation on the ground, the Russian representative explained that Russia had referred to the hypothetical ‘in order not to introduce again some information that Russia cannot disclose’” (WTO 2019, para. 7.115).

National security claims were rarely made in the GATT era, which is hardly surprising given the limited trade that took place across the Iron Curtain. As the knowledge-based economy ushered in an era of rising rents, there was a growing use by GATT members of power-based instruments such as the “grey area measures” (for example, so-called “voluntary export restraints” and so forth; Ciuriak, Bienen and Picarello 2013), as well as the use by the United States of the unilateral Super 301 tool (for example, to leverage the Structural Impediments Initiative commitments from Japan; Matsushita 1990). The Uruguay Round was in good part about banning the use of these instruments.

In recent years, these disciplines have been rendered in tatters as shown by the section 301-driven US-China phase one forced trade agreement — which gives a new meaning to the acronym FTA — and the acquiescence of the European Union in the US tariff rate quota arrangements on steel and aluminum to replace its section 232 tariffs (The White House 2021b).

Things get problematic in the digital domain because of the nature of cyber intrusions. The attack landscape is huge and growing rapidly with the proliferation of smart devices and Internet of Things applications. The number of cyberattacks is in the billions per year, mostly automated and virtually impossible to attribute (on the “attribution problem,” see, for example, Egloff 2019; and Nye 2017). Most attacks are private and criminal in nature. The costs of cybercrime are growing rapidly but are still on the order of only about one percent of GDP, which is small relative to other types of nefarious behaviour — so far, they are just part of the cost of doing business (Ciuriak 2021b).

Meanwhile, the public attribution of cyber incidents to state actors is a political tool, hence strategic in nature, and by the same token not to be taken at face value. As writers from Sun Tzu to Philip Knightly (author of The First Casualty) have underscored, deception is an inherent part of conflict (Ciuriak 2021c). Thus, Oliver Carroll (2019), reporting the revelation of US cyber actions against Russia’s power grid, raised the following questions: “Why was Russia being tipped off about supposedly important US assets in the Russian power grid? Had they been found? If the operation was real, how much did it represent a change in the normal state of affairs? And why was the news being broken now?”

When national security claims are made with commercial consequences, we therefore have an identification problem: is the claim part of commercial warfare for rent capture or is it legitimately national security? One may recall here Sweden’s invocation of GATT article XXI(b), which addresses traffic in “goods and materials…for the purpose of supplying a military establishment,” to defend a quota regime for footwear imports, on grounds it needed to protect its domestic footwear industry to ensure the supply of boots for the military in time of war (WTO n.d.). That claim was transparently trade protectionist and was rejected by the GATT panel, but what about the requirement imposed by the United States that ByteDance, the Chinese-owned startup whose TikTok app had gone viral in the United States and other markets, divest its US operations? What about measures that knocked Huawei from world number one in cellphone sales to number six (with not a little benefit to Apple’s market share)?

Rent Capture in the Data-Driven Economy

Countries can benefit from the digital data-driven economy in two general ways: as a producer and as a consumer. Countries that can establish a foothold in this economy through data-driven companies that are able to operate both domestically and internationally can compete for the large international rents that this economy generates. In the absence of those firms, countries can still benefit as consumers from digital services that are often freely provided. However, they face poor terms of trade as they contribute to the development of global data assets but do not share in the ownership and exploitation of these assets. In a world dominated by intangible assets, consumer-only countries accordingly face a shrinking share of global wealth.

As one response, many countries have moved to impose digital services taxes, which led to the threat of retaliation, and ensuing negotiations to develop a global framework. The result is the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)/G20 Inclusive Framework (OECD/G20 2021; OECD 2021). The redistribution of taxation rights is, however, very modest compared to the increase in the scale of profits shielded from tax through use of tax havens in the data-driven economy era. Dan Ciuriak and Akinyi J. Eurallyah (2021) suggest that, for the OECD countries, the Inclusive Framework is a $150 billion solution to what has grown into a trillion dollar-plus tax avoidance problem in the data-driven economy.

More importantly from the perspective of addressing rent capture in the data-driven economy, the Inclusive Framework does not take into account the value of data. A lower bound for the value of data that is generated in the OECD region can be set at the value of free internet services (which represent the other half of the barter-type exchange of free services for data). An estimate of this for the United States suggests it is on the order of two percent of GDP (Nakamura et al. 2018). For the OECD, this would imply about $1.2 trillion in value annually, of which two-thirds or more than $800 billion would be generated outside the United States. Clearly, this is a prize that is worth fighting over. It is implausible that countries will continue to allow it to flow across borders without compensation of some sort.

The Infrastructure of the Data-Driven Economy

Some 99 percent of the international flow of data is through submarine cables. Satellite relays account for the rest (although this might change with a rapidly growing list of entrants into low Earth orbit or LEO broadband satellite networks; Leins 2021). Accordingly, the critical infrastructure of the data-driven economy from a geopolitical/geoeconomic perspective is the submarine cable network and the connections to land-based broadband.

In this area, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Group of Seven Build Back Better World (B3W) are positioned as being in strategic competition/geopolitical rivalry. B3W is to have a digital component in due course but perhaps the more significant immediate competitor to China’s Digital Silk Road are private-sector projects such as the Facebook-backed 2Africa cable, which is slated to be 45,000 km long and to provide close to three times the total network capacity of undersea cables currently serving Africa (Ahmad and Salvadori 2020). This competes with the BRI’s 12,000 km Pakistan and East Africa Connecting Europe (PEACE) cable, which covers the east coast of Africa and links through Pakistan to Xinjiang in China (Haq 2021).

Figure 2: Facebook-backed 2Africa Cable

Figure 3: China’s Digital Silk Road Africa Connections

It is tempting to read much into such maps — and what is geopolitics if not about maps? For example, there is a palpable sense from the 2Africa map both of improved African access to digital services and of a flow of the data that Africa generates to Europe. There is an image of encirclement, exciting thoughts of “data colonialism” (e.g., Couldry and Mejias 2019). Similarly, the PEACE cable and its land link to Xinjiang graphically evokes the regeneration of the pre-modern Afro-Eurasian trading system (not to mention highlighting the bypassing of India, which is a strategic consideration for Pakistan; Haq 2021).

In reality, exactly what this means for strategic competition over and above the capture of market share in building and managing data pipelines is unclear. Submarine cables are typically owned by a consortium of telecommunications companies, and increasingly platform companies such as Google and Facebook — the 2Africa cable, for example, is being created by a consortium that includes Facebook in addition to Hong Kong-based China Mobile International, MTN GlobalConnect, Orange, Telecom Egypt, Vodafone and West Indian Ocean Cable Company. Moreover, they are subject to the jurisdiction and/or influence of multiple coastal states, in particular those with which they connect directly. Encryption may in the fullness of time limit the capacity of the owners and managers of cables — or governments tapping into them — to exploit them for espionage as they have been in the past (Burdette 2021). But in the meantime, it is “game on” in the contest to dominate the buildout of the infrastructure of the data-driven economy.

The Rules for Cross-Border Data Flow

Much has been written on who will write the rules for the digital economy. In this regard, the circumstances are very different from those that prevailed when the postwar rules-based system was developed. Then the United States was in a position of hegemony and trade was dominated by the North Atlantic region. Agreeing on rules was essentially an issue of the United States and the European Communities hashing out a compromise (see, for example, Keohane and Nye 2000; Curtis 2002). By contrast, the digital economy is evolving in a multipolar context with trade dominated by East Asia, which features a large concentration of global 500 firms and a highly developed international division of labour in its production networks. While there is no consistent data on the scale of cross-border data flows (and there are problems in even defining cross-border data flows given the way internet linkages can route domestic transmissions through connections in other countries), available evidence suggests that the country with the largest cross-border flows is the country at the heart of these networks, namely China (including Hong Kong) — see, for example, Tsunashima (2020). While China imposes extensive censorship on individual access to non-Chinese social media and news sites through its Great Firewall, it nonetheless has a commercial interest in facilitating the flows of information that drive the production networks in which it is embedded. Its interest in the Digital Silk Road is then self-explanatory.

Given the competition in building the global infrastructure for data flows, the de facto regime for international data flows will thus feature a heavy admixture of China’s policies, US policies and, of course, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation/Digital Single Market policy package.

Interoperability considerations and network effects tend to drive compliance with the most stringent requirements — the so-called “California effect” (see, for example, Vogel 1995; Perkins and Neumayer 2012). As regards privacy, the European Union’s version of this effect — the so-called “Brussels Effect” — appears to have the inside track (see, for example, Bygrave 2020 for a review of international trends in adopting EU-style data privacy law). As regards national security, the US-China confrontation is driving the rapid development of policy regarding the definition of what is “sensitive” data and the terms and conditions under which such data will be allowed to move across borders (and in this regard, China seems more advanced in articulating a framework through its new Data Security Law).

Discussion and Conclusions

Data flows over the internet were born free. Then data became valuable — and dangerous. Currently, immense amounts of data continue to flow across uncontrolled borders while national authorities work out how to capture the value and attenuate the dangers. The direction of change is from free to conditional movement.

The private sector grew up with an internet that was as close to “free and open” as one can get. The natural interest of business, private individuals and the technological community is to push for as large as possible “data Schengen zones” and minimal formalities for data flows across these zones.

The technological conditions matter a lot. There is an arms race between encryption and decryption. Accordingly, it will be hard to settle on hard and fast rules, since risk tolerance for cross-border flows will vary in line with the degree of confidence in cybersecurity. The direction of change is companies devising ever better protection for flows from intrusions by private parties — but governments insisting on backdoors because private security is seen as public insecurity.

Countries do not cede sovereignty decisions to international organizations but they do agree to international conventions like the Chicago Convention for air transit. Bilateral analogues for data already exist in the form of safe harbour agreements but the challenge will be to develop conventions that facilitate flows and minimize frictions while taking into account both the myriad privacy/security concerns and value capture. The discussion of the international framework for data flows has yet to come to grips with the value of data.

The prospects for DFFT in the data-driven economy do not seem especially bright. We see European distrust of US surveillance, China’s elaboration of new data security laws with stringent cross-border clearance requirements, US restrictions on Chinese digital economy operators on national security grounds, India’s exclusion of Chinese apps, Russia’s national internet and so forth. Indeed, an official in Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, noting the defection of countries such as India from Japan’s push for its DFFT standard, is quoted as saying, “The ‘T’ in DFFT is gone” (Tsunashima 2020). The concerns about security and data sovereignty reviewed above mean that the “FF” in DFFT are gone as well.

What is left is “D,” which in this case can also be considered the grade the main players have earned for stepping into obvious traps (think Thucydides); overplaying hands (imposing export restrictions with the usual unintended consequences of interventions into poorly understood industrial structures); and painting themselves into corners with overblown and diplomatically toxic rhetoric.

We thus face a reality that will feature “unfree data flow with no trust.. The interest of all countries is to minimize the mess. From this perspective, the critical next steps would seem to be as follows:

- Acknowledge the role of technological conditions in shaping regulation. “Democracies” face the same technological conditions as do “authoritarian countries” (whatever those labels actually mean in terms of responsiveness of governments to societal challenges and needs). Competent regulatory reform or Darwinian selection will lead to more or less the same rules. The critical thing in minimizing the mess is to avoid the latter route.

- Arrive at a reasonable rent-sharing agreement regarding the data rents generated in the data-driven economy (i.e., a détente). Elsewhere, I have written of a new “Yalta moment” (Ciuriak 2021d), recalling the establishment of de facto spheres of influence of the post-World War II Great Powers (allegedly on the back of an envelope). Something similar is needed now. The Inclusive Framework is a step in the right direction but, as noted, fails to address data rents.

- Put the national security genie back in the bottle. If WTO commitments made in the pre-digital age are untenable in the digital context for irreducible security reasons, this should be acknowledged and a good-faith renegotiation should be undertaken under established WTO procedures, rather than concerns being acted upon through non-transparent national security claims that undermine WTO dispute settlement (Ciuriak 2021e).

- Upgrade the WTO e-commerce negotiations into a full-fledged Digital Round (Ciuriak 2019b). This should be launched on the basis of a white paper that explains why and how the digital environment is different from the material environment and the issues that these differences raise for existing WTO rules and disciplines.

- Establish a new quantitative framework for assessing the impact of international commitments suitable for the intangibles economy and taking into explicit account the value of data. It is way past time for quantitative assessments of trade agreements to have the caveat that perhaps the most important issues in the agreement (intellectual property and the value of data) are not explicitly addressed (Ciuriak 2017). It is a cliché to say that one can’t manage what one doesn’t measure, but it will prove impossible to rapidly move to a new governance regime fit for purpose for the digital age unless we actually measure things properly. For the trade policy community, this starts with the impact of commitments in the area of e-commerce and data.

All this is probably a bridge too far for the international community at the moment, given the open strategic contest for rents and the nebulous but omnipresent national security concerns. We should accordingly be realistic about the possibility of restoring a functional rules-based order in the near term, however much that is to be desired in the longer term.