Following the announcement of a breakthrough in the trade talks between the United States and Mexico, economists and industry leaders both have been speculating on what the revised deal means for the continent.

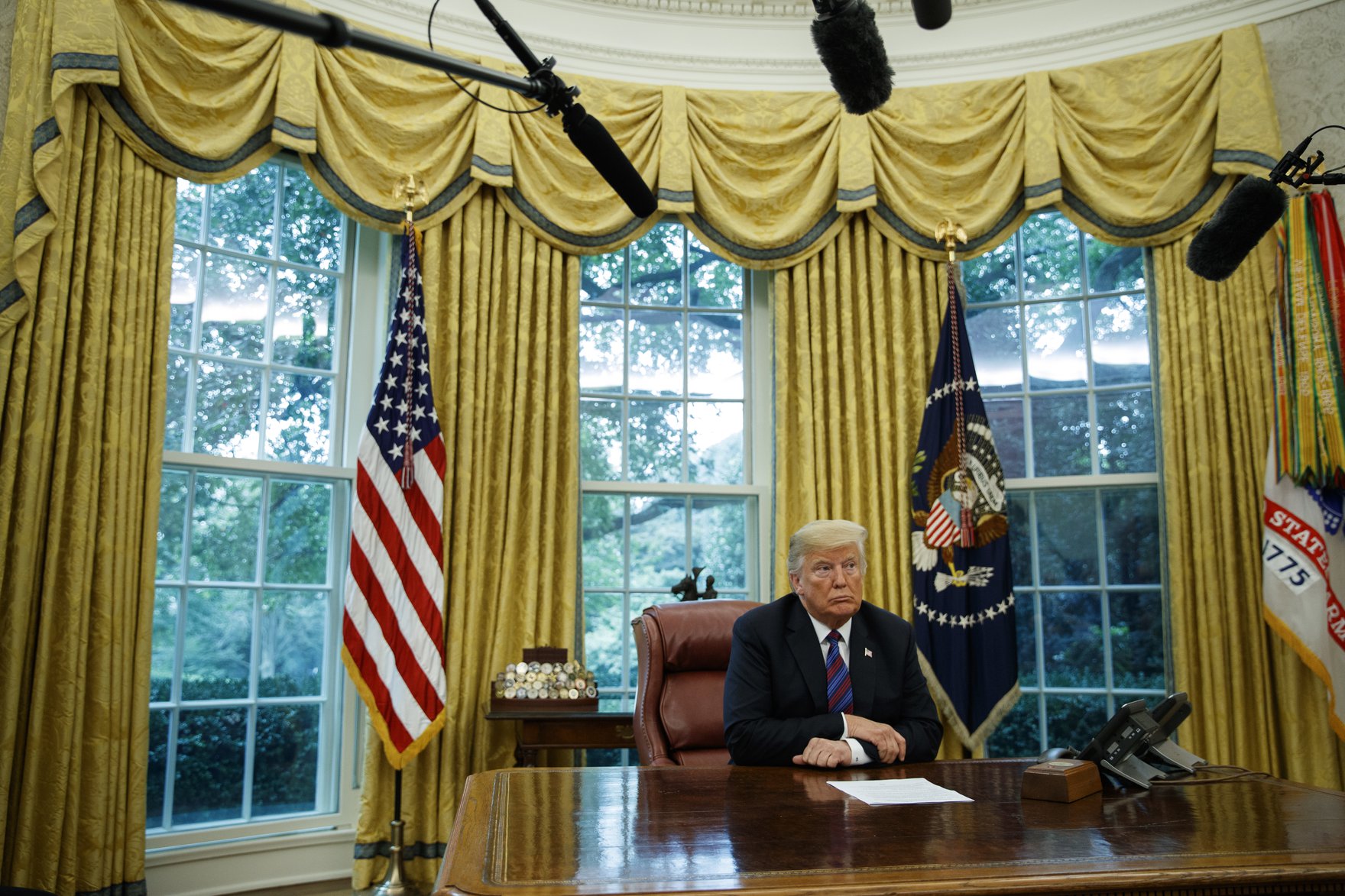

On August 27 — more than one year after US President Donald Trump launched the renegotiations of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) — he said that the countries had reached an “incredible” bilateral agreement.

While Mexican negotiators presented the development as a victory, policy experts expressed concern that Canada — one of the three NAFTA partners — would be excluded from the deal.

Later that day, during a televised phone call with Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto, Trump said he might cut separate trade agreements with each partner.

During the call, he described the Canadian economy as “a smaller segment” compared to Mexico, which he called “a very large trading partner.”

Trump even said he wanted to name the revised deal the “United States-Mexico Trade Agreement” because NAFTA had such “bad connotations.”

While Peña Nieto stressed that his administration was “waiting for Canada to be integrated into this process,” Luis Videgaray, Mexico’s foreign minister, caused controversy when he said Mexico would be willing to proceed without Canada.

“There will be a free trade agreement between Mexico and the United States,” Videgaray said in a press conference on Monday. “Regardless of what happens in the negotiations with Canada.”

Since Mexico has repeatedly expressed its desire to stick together with Canada for any deal, many Mexican analysts were alarmed by Videgaray’s comments.

“Canada is an ally and friend,” said Manuel Molano, adjunct-director of the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, an economic think tank. “I seriously doubt the advantages of turning our back on that relationship outweigh the disadvantages.”

There is no certainty that Canada will sign the revamped deal. Tensions between the Trump administration and their northern neighbours have been running high for months. The US president forced Canada out of NAFTA talks this month and launched an angry personal attack on the country’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in June.

Adam Austen, a spokesman for Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs Chrystia Freeland, said Canada would not act against its own interests.

“We will only sign a new NAFTA that is good for Canada and good for the middle class. Canada's signature is required,” he said.

Any agreement without Canada would be a downgrade for Mexico. Trade between the two countries has increased sevenfold since NAFTA came into force, and Canada is Mexico’s second-largest export market, buying 2.8 percent of its total exports in 2016.

An exclusive deal would also increase Mexico’s dependence on the United States during a particularly volatile period in bilateral relations.

“Right now, Mexico needs to strengthen its regional alliances,” Molano said. “But I think the probability [of a bilateral deal] is higher now than ever before.”

Trump triggered the NAFTA renegotiations in August last year, blaming the 24-year-old trade agreement for the decline in iconic US industries such as the auto sector. The Republican president has repeatedly blamed Mexico for US job loss, saying that manufacturers have been drawn south of the border with the promise of lower wages.

The Trump administration says the new trade deal, however, will support domestic manufacturing. US and Mexican negotiators spent several weeks hammering out their differences in bilateral talks that addressed issues related to the agricultural and auto sectors, among others.

The 16-year deal maintains a zero-tariff policy — the principle that helped integrate supply chains across NAFTA territory. The agreement also includes updates to rules on agricultural products, pharmaceuticals and information technology.

Most importantly, the two negotiating teams have agreed on more stringent rules for car manufacturers. Under the new requirements, 75 percent of a vehicle’s content must be made in Mexico or the United States, up from 62.5 percent. The deal also stipulates that 40–45 percent of that content be made by workers earning at least US$16 per hour — a measure designed to dissuade manufacturers from moving to Mexico, where car workers earn an average wage of around US$2 an hour.

According to a White House press release, these rules will “incentivize billions a year in vehicle and automobile parts production in the United States, supporting high-wage jobs.”

But Valeria Moy, director of the think tank México ¿Cómo vamos?, expects US consumers will soon bear the costs of these changes.

“Low wages in Mexico mean cars are cheaper for North America and the world,” Moy said. “When cars are produced in the United States, they become far more expensive.”

Moy said the details of the preliminary agreement are still unclear.

“We don’t know the time frame for the introduction of the new rules,” she said. “We also need to wait and see how Canada reacts.”

In spite of these uncertainties, the announcement of a deal sent auto stocks soaring. The Mexican peso and Canadian dollar also strengthened on optimism that Canada would soon sign on.

But even if Canada finalizes the agreement, the treaty still has to pass through the legislatures of all three partner countries. The November mid-term elections in the United States could also hand Congress to the Democrats, in which case Trump may struggle to win approval.

“There is really nothing worked out,” said former Mexican congressman Agustín Barrios Gómez. “We are all being used in Trump’s game.”

Barrios Gómez was surprised and concerned that Mexico was willing to move forward without its Canadian partners. He sees the revised deal as an act of political posturing by a US president determined to secure a superficial win.

“The deal suits his political marketing ahead of the November election,” Barrios Gómez said. “He wants to say he is the president that rewrote NAFTA. But I don’t think his deal is actually going to benefit anyone.”