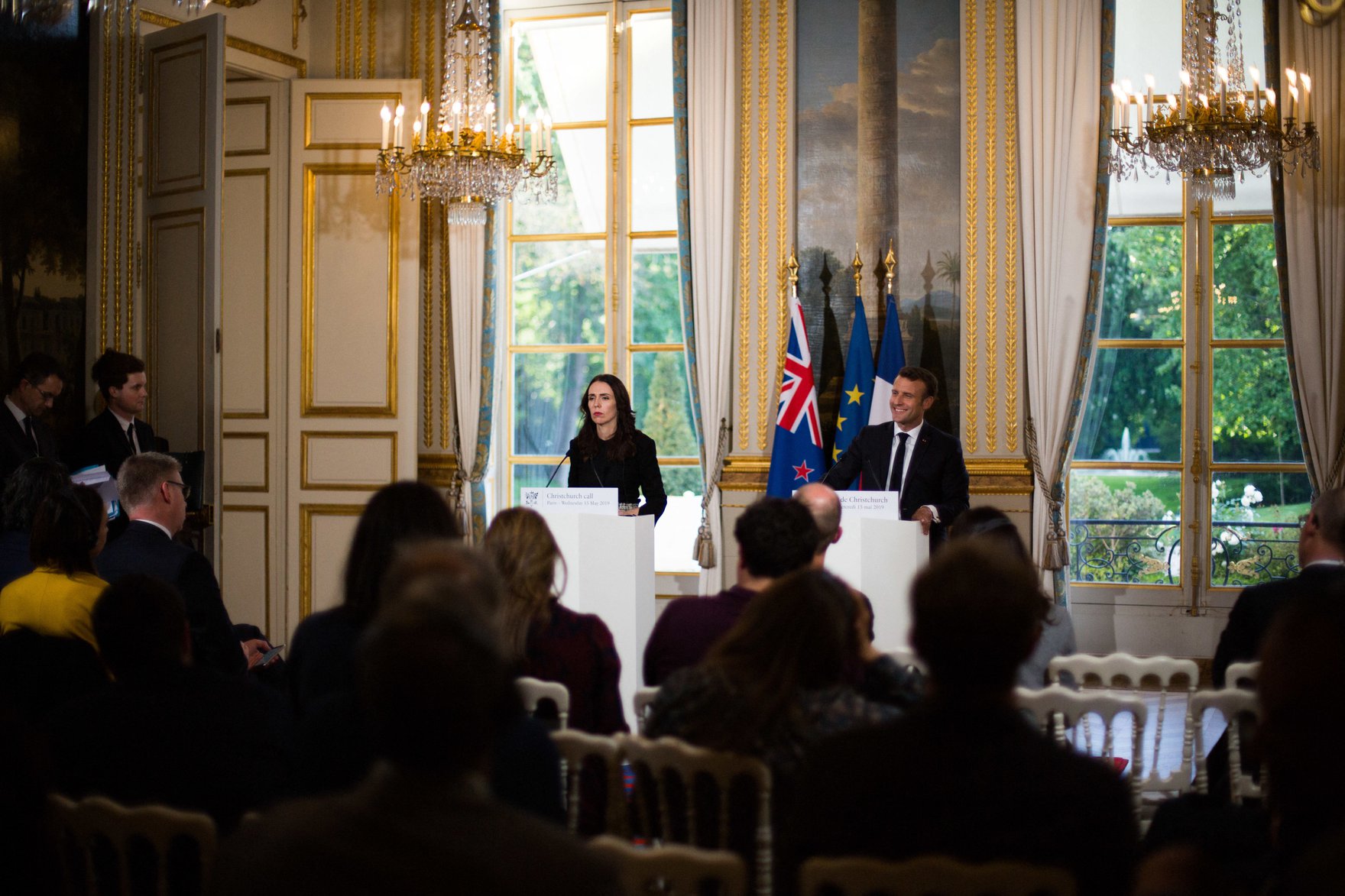

On March 15, 2019, a terrorist attack against two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, was broadcast live on social media for 17 minutes and viewed thousands of times before being removed. Two months later, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern convened government leaders and technology sector representatives to sign the Christchurch Call — a pledge to eliminate terrorist and violent extremist content online.

Since then, hearings, trials, committees and regulatory boards around the world have debated content moderation and removal policies at length, often in the context of other violent and extremist content that has circulated since March 15, 2019. Two years after the adoption of the Christchurch Call, what has changed? We asked three experts to consider how regulatory responses — born of New Zealand’s voluntary, non-binding governance initiative — have impacted the spread of extremist content, and what hurdles lie ahead. This article compiles their responses.

Robert Gorwa, the Centre for International Governance Innovation

Looking back to 2019, the political choice to develop the Christchurch Call (a voluntary initiative negotiated with platform companies by the New Zealand and French governments) is made even more interesting when seen in the wider context of the policy response that was being developed just across the Tasman Sea. Australia’s controversial Sharing of Abhorrent Violent Material legislation was very different in both style and substance, and the New Zealand leadership has since been lauded for their decision to not impose stringent liability frameworks based around individual pieces of content and to instead seek to shape firm content moderation processes in a softer, collaborative and systems-oriented manner.

The stakes are especially high given that the GIFCT has famously been plagued with transparency and accountability issues in the past.

Many of the major outcomes of the Christchurch Call — the deliverables that firms committed to as part of the Call’s implementation — are still a work in progress. A key aspect of increasing industry coordination has happened through a very informal industry body called the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT), which has been institutionalized with legal status as a charitable entity, a small amount of permanent staff, an advisory group of civil society organizations and government actors, and a number of formalized rulemaking working groups. This will be the space to watch to understand the impact of the Christchurch Call going forward, as decisions made by GIFCT members (for example, regarding the infrastructure of their hash-sharing databases) promise to have huge ramifications in the rapidly evolving era of algorithmic content moderation.

The stakes are especially high given that the GIFCT has famously been plagued with transparency and accountability issues in the past. Will the recent restructure and inclusion of civil society in an “advisory” capacity have a meaningful impact, or will the GIFCT’s activities fulfill critics’ conception of it as an opaque and deeply problematic locus of private power? It has all culminated in an important case study into the possibilities — and potential limits — of a collaborative platform regulatory approach that is still nowhere near completion.

Dia Kayyali, the Advisory Network to the Christchurch Call

The multi-stakeholder nature of the Christchurch Call is promising but not quite fulfilled. Moving forward will require some tough conversations. Two, in particular, stand out.

First, governments, companies and international bodies don’t have a shared definition of terrorism or extremism. It’s hard to eradicate content when we don’t agree on what that content is. However, the most influential lists, including those maintained by the United States and the United Nations, are dominated by “Islamist” groups, and do not include many far-right groups. Current definitions and the policies based on them are not effectively addressing white supremacists, specifically, or the far right, more broadly. We urgently need to solve this problem, especially considering that experts are warning about the growing far-right threat.

Current definitions and the policies based on them are not effectively addressing white supremacists, specifically, or the far right, more broadly.

Second, intelligence agencies and law enforcement are increasingly engaged in this work. While their involvement is unsurprising, the Call should not ignore the variety of human rights abuses that agencies all around the world have committed in the past in the name of countering terrorism, particularly against minority communities and Muslims.

As the anniversary approaches, civil society is committed to continuing to build relationships between stakeholders. This new model deserves a chance to be successful, and we are eager to sit at the table with companies and governments and lend our expertise to these difficult issues.

Sonja Solomun, the Centre for Media, Technology and Democracy

Since the adoption of the Christchurch Call, governments around the world have followed suit with a range of interventions, including non-binding codes of conduct in the European Union and a “duty of care” in the United Kingdom. Despite the recent influx of both voluntary and “hard” regulatory efforts, the last two years have materialized many of the early concerns expressed by the platform governance community before the Christchurch Call was implemented — that the lack of meaningful enforcement would simply treat symptoms of the problem behind online extremism; that broad definitions of “terrorist” or “extremist” content could invite politically motivated misuse; and relatedly, that the designation of “terrorist” is, itself, inherently political. The Call also paved the way for regulatory reliance on technical evaluations, namely, through upload filters and automated tools, as seen in Europe’s alarming recent adoption of the online terrorist content regulation, for instance, despite wide consensus among practitioners and technologists about their lack of efficiency and merit.

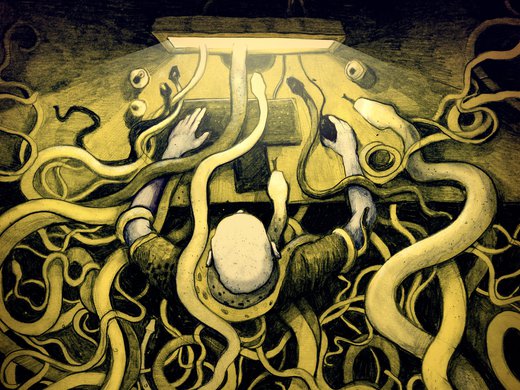

Rather than continuing a game of whack-a-mole with harmful content, we need to contend with the ecosystem of online radicalization and extremism, which finds meaning and amplification through both technical and social contexts.

This points to a central hurdle ahead — the overdetermined regulatory and policy focus on content moderation and content-related harms, which has ushered in a range of take-down measures. Anti-Muslim extermism has, unfortunately, remained alive and well in the aftermath of the Christchurch Call, including on YouTube, where the Christchurch mosque shooter was radicalized. Beyond technical fixes and harms-based interventions, governments need to ensure platforms explicitly commit to protecting Muslim communities. Rather than continuing a game of whack-a-mole with harmful content, we need to contend with the ecosystem of online radicalization and extremism, which finds meaning and amplification through both technical and social contexts. A massively challenging next hurdle will be to rethink the fraught distinction between online and offline harms. As many have observed, extremism is circulated and enabled through a broader ecosystem of different platforms, such as payment services and file-sharing websites, among others. Content moderation, which seemingly centres content, is also about maintaining the broader digital infrastructure. Addressing this wider ecosystem will require coordinated global responses to how content governance intersects with data protections and competition policy more broadly. While there are no easy answers in sight, the Christchurch Call reminds us that impacted communities and civil society cannot be sidelined from these crucial next steps.