As the spring meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank kick off in Washington, it is clear that the critical challenge facing Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the IMF, is to preserve the broad international consensus on multilateralism that has prevailed since 1945. Her task is all the more daunting in the face of ill-informed and ultimately counterproductive attacks on international cooperation launched by Donald Trump’s administration. Martin Wolf has authoritatively debunked the commerce secretary’s assessment of the current state of international trade. But no well-reasoned analytical critique of uninformed views can be expected to change minds.

If there is a conscious game plan discernible behind the administration’s policy statements (rather than inchoate pandering to a political base) it is to dissolve the bonds of multilateralism. That would create a void in which the United States could negotiate better trade deals under an “America First” trade policy. While the United States would undoubtedly be able to exert its unequal bargaining power against smaller countries to get a bigger piece of the pie, the danger is that the pie shrinks. At the same time, the United States would find it increasingly difficult to mobilize a “coalition of the willing” in response to the security and other threats that will inevitably arise. This is why the administration’s approach is fundamentally counterproductive.

Historically, America played a role that the late Charles Kindleberger described as an unselfish hegemon. The risk to the global economy is that that role may be coming to end. One can remain cautiously optimistic that financial and economic self-interest will act as a brake on rash actions. Nevertheless, the risk remains.

Given this threat, the managing director has to either keep the IMF’s largest shareholder engaged in multilateralism or provide the glue that keeps the rest of the international community together in the face of a selfish hegemon. This would be no mean feat. And, arguably, one Lagarde alone must shoulder.

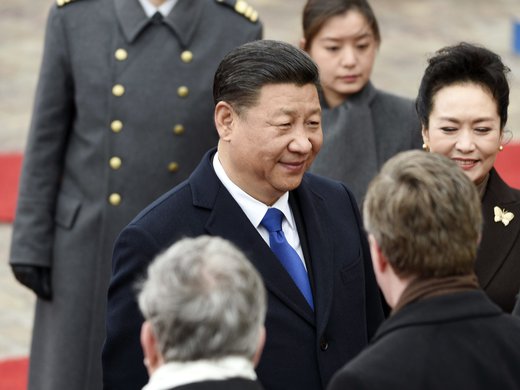

If the United States is no longer willing to take on the task of “herding cats” in the interests of international cooperation, who will? China is the logical candidate, and President Xi Jinping has indeed provided a calming influence, in contrast to president Trump’s version of Twitter diplomacy. But China is not yet ready to lead and, in any event, others are unwilling to follow. While Germany could provide steady mature leadership, Berlin is tied up with Europe’s internal challenges.

Sadly, it seems, the international community finds itself in a position similar to 1929, when in response to the financial crisis that heralded the onset of the Great Depression, as Kindleberger observed, the Bank of England “couldn’t” and the Federal Reserve “wouldn’t” provide the public good of international financial stability needed to preserve the gold standard and the multilateral framework of the day. That failure led to monetary disorder, charges of currency manipulation — as some countries exited the gold standard while others remained — plus trade restrictions and bilateralism that transformed the way nations regarded the global economy, turning it into a zero-sum game. From that disorder and the economic dislocation of the Great Depression, the IMF was born. The role assigned to it was to promote international monetary stability that would facilitate multilateralism. It worked.

Christine Lagarde must keep it working. To do so, she must strengthen the governance of the Fund. This is because to keep the United States engaged, US concerns regarding exchange manipulation must be addressed. The perceived failure of the IMF to “call out” what the US Treasury considers to be clear cases of currency manipulation has been a long-standing irritant. That would require the managing director to speak truth to power and strengthen the Fund’s capacity to punish members deemed guilty of such practices. Lagarde and the Fund are in a difficult position, however, because they lack a clear means to encourage countries to desist from manipulation. This lack could erode their credibility: an institution whose injunctions are ignored without effect could lead to the perception of impotence and irrelevance. But for the IMF’s exchange rate surveillance to be more muscular and its implications accepted, members must agree to be bound by its findings. That is unlikely if the basic governance of the institution is not viewed as legitimate.

Alternatively, if Lagarde is to provide the glue that keeps the rest of the global community together in the face of a selfish hegemon, they must have confidence that the IMF truly represents their interests and is not unduly influenced by its largest member or the other advanced countries that dominated the global economy in the second half of the twentieth century. The simple fact is that no sovereign state will delegate powers to a supranational organization if it is not rules-based and broadly representative of the global economy.

All of this underscores the need for IMF quota reform. Quotas are the basic foundation on which IMF governance is based. In some respects, they can be considered as members’ ownership shares, determining voting power of the membership. Yet, reflecting the unique nature of the IMF, quotas also determine a member’s commitment to provide funding if required, as well as the amount of resources the member can borrow. While the various roles of the quota may complicate efforts to achieve reform, the biggest obstacle is that it is a zero-sum game: if one country’s share increases, the share of some other country must fall.

Given the potential existential threats posed to multilateralism in general and the Fund in particular, the need for quota reform is urgent. Unfortunately, the prospects for near-term change are remote. Nothing is likely to happen in 2017. This is because the United States has a de facto veto on the process and, despite its importance to the global economy, it is not high on the priority list of the Trump administration. In any event, senior Treasury appointments are waiting on senate confirmation and, even after they are on the job, substantive discussions would have to wait until officials are briefed and engaged in the issue. At the same time, Germany, which chairs the Group of Twenty (G20) meetings this year, has signalled that it does not want to tackle an issue that is unlikely to be resolved in its election-truncated year. So, if reform is to happen by the IMF’s self-imposed deadline of late 2018, it will have to happen on the watch of Argentina, which will chair the G20 next year.

This provides an interesting opportunity for a new government in Buenos Aires intent on engaging in a productive relationship with the global economic order after a decade of policy heterodoxy. But that opportunity is a double-edged sword: the risks of failure are high. The biggest impediment to quota reform may not be the United States, which would welcome reform if it facilitates more robust IMF exchange rate surveillance. Rather, quota reform is so difficult because it would require other advanced countries to give up quota share. This is largely a Group of Seven (G7) fight. And, in this regard, as 2018 chair of the G7, Canada is in a position to help Argentina push meaningful quota reform.

Effective cooperation between Argentina and Canada could be critical to getting an agreement. However, these efforts would still have to overcome the zero-sum nature of quota reform. One way of clearing that hurdle is to embed quota reform in a broader game of preserving multilateralism. A broader game that would generate benefits to compensate those whose shares would fall under meaningful quota reform. Getting to that point would require innovative thinking.

Ironically, perhaps, it is the threat to multilateralism — and the potential costs to the global economy — that might create the catalyst for a critical mass of countries to take the leap and embrace reforms, thereby strengthening the ability of the IMF to rebuild a robust consensus in favour an international order based on cooperation — an order governed not by the whims of one but by balancing the interests of all.