Uncertainty seems to be the only certainty in the Trump administration’s unconventional approach to governing. Uncertainty attends every incoming administration, of course. But past White House teams have moved to assure the American people and foreign allies of policy continuity in core areas and to reduce uncertainty surrounding possible new initiatives. That cannot be said of Donald Trump’s team.

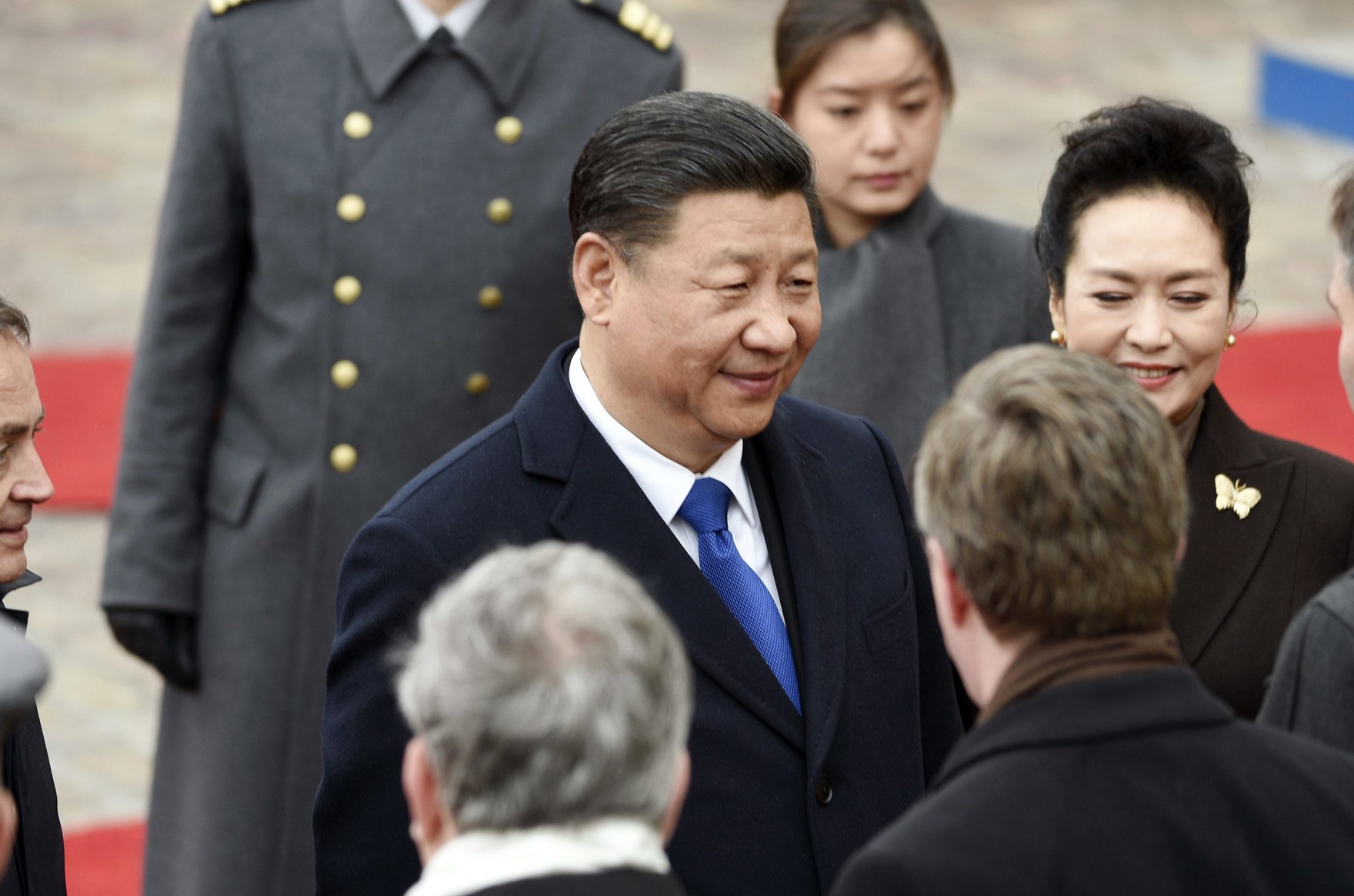

As China’s President Xi Jinping meets his counterpart for the first time, nowhere is uncertainty greater than with respect to the administration’s potential impact on the multilateral trading system.

Trump’s pre-inaugural misstep on the decades-long one-China policy — publicly musing about whether to recognize Taiwan, Province of China — was explained by partisan supporters as a negotiating tactic deftly designed to create a trade-off in which endorsement of the status quo is offered in exchange for better access to Chinese markets for US companies. And while that outcome cannot be ruled out, it seems more likely that Beijing saw through that ploy and countered with a blocking strategy.

President Xi may well have signalled that China would be less cooperative on some other issue on which Washington needs Beijing’s assistance; North Korea comes to mind. Or, Beijing may have simply reminded Washington that it feels more strongly about the one-China policy than any other issue and that China can buy airplanes, pork and soybeans from other suppliers. In any event, Trump subsequently reversed course and endorsed the status quo.

Moreover, since the inauguration, rather than coordinate messages and project policy coherence, the Trump administration has demonstrated deep dysfunction, as Senator John McCain and others have observed. This confusion was on display in February when US Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly and US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson travelled to Mexico to alleviate Mexican concerns about trade and deportations even as the White House was issuing contradictory statements.

More recently, whether by accident or by design, the administration introduced uncertainty into Group of Twenty (G20) multilateral discussions. At the insistence of the US delegation, G20 finance chiefs meeting last month in Baden-Baden, Germany, watered down communiqué language on the need to resist protectionism, language that had been G20 “boilerplate” for years. This episode may have reflected a novice Treasury secretary’s introduction to the kabuki theatre of G20 communiqué drafting and language that, frankly, might have gotten stale and no longer served its purpose. If intentional, however, the objective may have been twofold: first, to underscore the administration’s intention to renegotiate trade deals and, second, to establish an aura of intransigence that would provide a negotiating edge in those negotiations.

But a strategy of using intransigence to force the other party to concede only works if the threat to walk away from the table is credible. If it is not believed, the strategy can backfire as the bluff is called. (As evidence, the Freedom Caucus’s demonstration that it would not be herded by White House threats to force a vote on the American Health Care Act has tarnished the president’s reputation as a deal maker.) In such circumstances, the party making unreasonable demands may feel compelled to follow through on a reckless threat that is harmful to both sides to “prove” intransigence or lose credibility. Such an outcome could lead both parties further and further from a cooperative outcome that maximizes the benefits to both.

The problem is that uncertainty increases the “noise” and masks the “signal” regarding the administration’s policy intentions, raising the possibility of miscalculation and policy error. The immediate threat as the leaders of China and the United States meet is to the international trading system.

In the wake of its defeat on health care reform, the White House has indicated that it intends to tackle tax reform. The risk is that recent congressional discussions on border adjustment taxes are used as justification for an across-the-board tariff. Border adjustment taxes can be an important element of broad corporate tax reform, as Alan Auerbach and Michael Devereux have argued. And, if implemented in a manner compatible with international obligations, they need not pose a threat to the international trading system. In the current environment, however, the president could act on border adjustment taxes without waiting for Congress to deliver other elements of a reform package, citing his dystopic vision of the United States as justification and Richard Nixon’s 1971 declaration of an economic emergency to impose import surcharges as precedent.

This unbundling, motivated by political factors, particularly the White House’s need to secure a “win,” could unleash a trade war. Tit-for-tat trade tariff increases would be destructive to trade and prospects for global growth. Thankfully, two factors might limit this risk.

The first is the development of global supply chains that allocate production on a global basis, with low-value-added inputs and assembly allocated to low-wage countries and high-value-added inputs (design and engineering) undertaken in high-wage countries. Ill-considered policy that disrupts these chains and results in a trade war would have adverse consequences for US firms that have made long-term investment decisions based on the assumption that they would have access to global markets. These firms would lose market value as they become less competitive compared to foreign firms that continue to exploit global production chains.

In this respect, while lashing out at China and other perceived foes with tariffs may temporarily protect some manufacturing jobs, other jobs would be lost. In the meantime, firms that have lost value are less likely to invest in the high-value-sector activities. Over time, US firms would not only lose market share in global trade, but also the technological edge which for the past 70 years has allowed American industry to dominate global markets. In view of these potential effects, it is possible the administration would balk at unleashing a trade war once corporate America explains the potential consequences.

This outcome is not assured. Yet, if the White House were to proceed with tariff measures that threaten corporate America’s long-term interests, Congress could act to reverse the president’s actions. This is the second factor that may limit the risk to the global trading system.

The reason why Congress might act is straightforward: money talks in American politics, mid-term elections are coming, and as the health care debacle demonstrated, Trump needs Congress. Political self-preservation may outweigh fealty to the president, and Republicans facing re-election may simply be unwilling to risk a backlash from their well-funded corporate constituencies. If this scenario does play out, it would once again demonstrate the genius of the Constitution’s checks and balances.

There is reason to believe, therefore, that trade trumps uncertainty — that the potential costs of unleashing a global trade war would constrain impetuous policy action. But, recall: the only certainty about the Trump administration is uncertainty.