When I was studying for my comprehensive exams in international trade in grad school roughly 30 years ago, I read an excellent survey of the field by Wilfred Ethier. I recall his assertion that, of all the trade theories that he thought as a grad student were most divorced from reality, factor price equalization was, in hindsight, one of the most powerful.

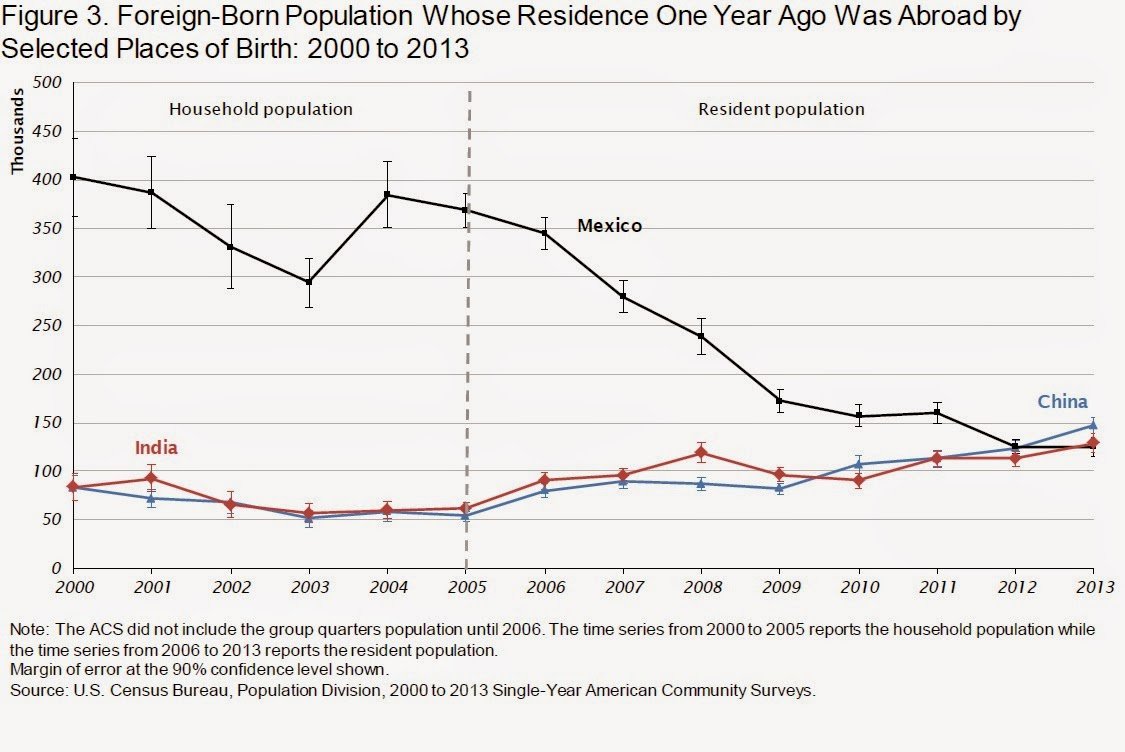

I was reminded of that survey article by a recent study by the US Census Bureau, here. The study documents a steady decline in migration of workers from Mexico to the United States as illustrated in the chart below:

Now, for the avoidance of doubt, migration is a hugely complex issue and there are undoubtedly many, many factors — idiosyncratic, secular, economic, social and political — behind the trend. But the trend is clearly discernible. And that trend led me back to Wilfred Ethier’s observation on the factor-price equalization theorem.

In brief, the theory is that free trade in goods can substitute for the free trade in factors in equalizing factor payments. So, trade liberalization that promotes a narrowing price differential between two countries and, in the limit, results in the law that one price should lead to a narrowing of differentials in factor payments — wages, say.

A heuristic proof of the theorem could be structured as follows:

First, assume a vector of prices in the economy, p, are determined by profit-maximizing firms with unit cost functions given by: c = c(w).

With p = c(w) domestically, and p* = c(w*) in the foreign country, trade liberalization that facilitates arbitrage (and assuming away transportation costs, etc.): c(w) = c(w*).

If technology is shared, and there is a unique mapping between combinations of factors and prices, the two cost functions imply that factor prices are equalized.

It is 20 years since the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA) was signed by the United States, Mexico and Canada. And because it is fair, I think, to assume that Mexican workers seeking entry into the United States are higher wages, a trade agreement that contributes to rising wages would reduce the economic incentives to migrate.

Caveat: I’m not saying that NAFTA is the sole or even the most important factor behind the trend in the chart above. But if it is, it would be a triumph of Wilfred Ethier’s assessment.