As the reverberations from Donald Trump’s re-election reshape the global order, we are going to find that many of our institutions, policies and ideas will not provide us with the protection that we had supposed. Chief among these is the belief that when it comes to internet governance, over-aggressive government regulation of US online giants such as Meta and Google is more of a threat to Canadians’ liberty than these companies themselves.

In a cruel but unsurprising twist of fate, it turns out that strong government regulation was the very thing we needed in order to address not just unchecked corporate power but also undue US influence on our economy and society.

As I warned almost three years ago in a CIGI opinion piece, these companies are not bulwarks against government tyranny. They’re for-profit corporations that reflect dominant US values, which may or may not involve fealty to free expression. And they are uniquely vulnerable to US government pressure. They depend on the state for contracts, for favourable regulations and trade deals. The corporate-state relationship is often symbiotic, but at the end of the day, the state rules because it sets the rules.

This relationship is always there, but it’s turbocharged under authoritarianism of the type US voters have just opted to introduce, in which neither companies nor individuals can count on the protections provided by the rule of law.

We already have concrete examples of Trumpism in action. Even before the former president emerged victorious on November 5, Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos, the third-richest person in the world, who also controls the inescapable global cloud platform Amazon Web Services, bent the knee, blocking his paper’s planned endorsement of Vice President Kamala Harris.

It appears Bezos feared retaliation should Trump win, but certainly not if Harris had triumphed, which encapsulates perfectly both the difference between authoritarianism and democracy, and the essence of the emerging United States under Trump. As former Post editorial board member Robert Kagan, who resigned in protest, noted, “Trump has threatened to go after Bezos’ business. Bezos runs one of the largest companies in America. They have tremendously intricate relations with federal government. They depend on the federal government.”

Following the election, the major US tech leaders lined up to congratulate the convicted felon, adjudicated rapist and insurrectionist, who has announced plans to round up millions of people, then imprison and deport them.

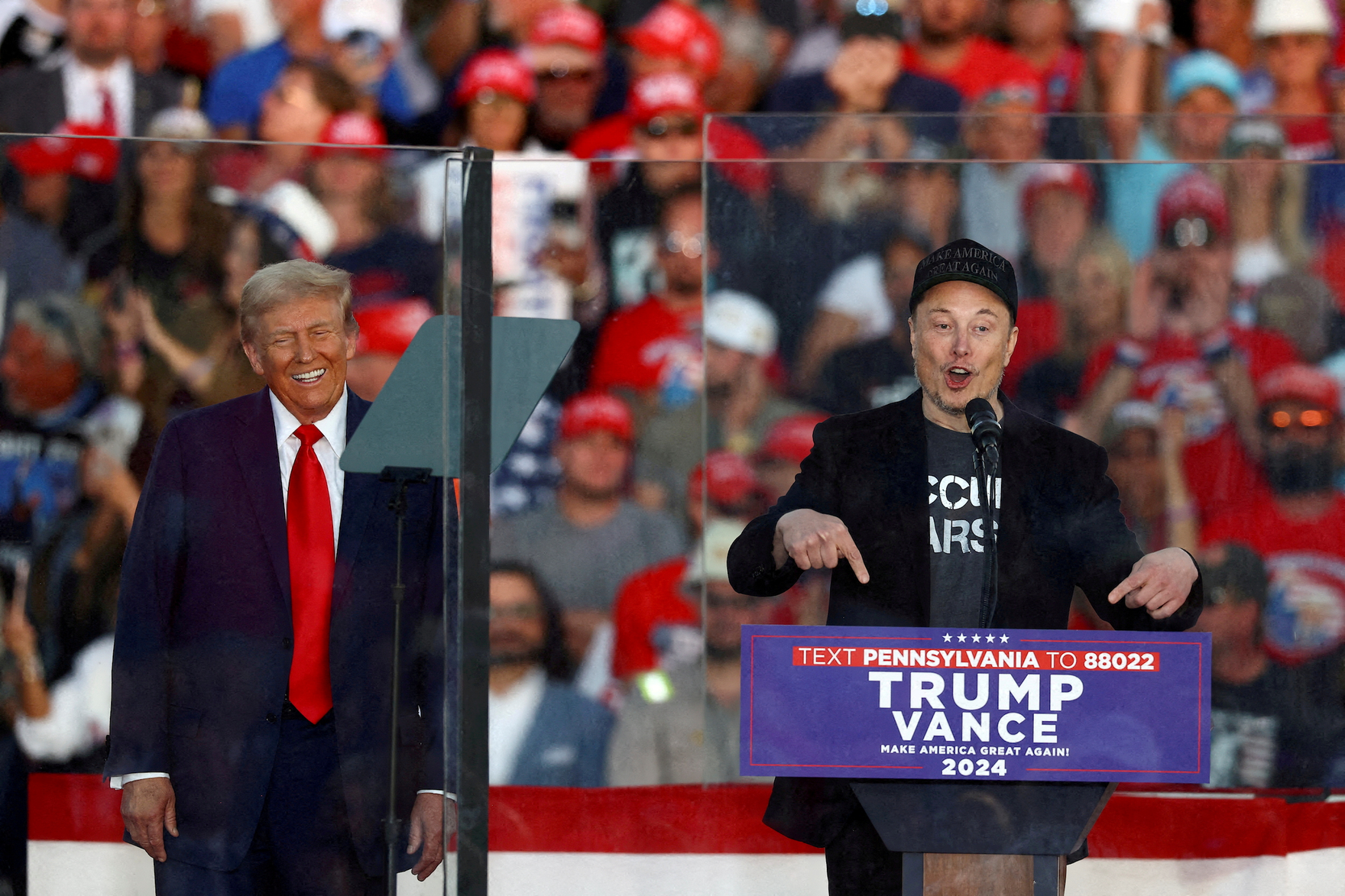

In keeping with this tech-authoritarian synergy, X owner Elon Musk, now in Trump’s inner circle, reportedly manipulated his social media platform to favour Trump in the months leading to the election, demonstrating a seemingly closer relationship to an authoritarian government than has been proven between TikTok (whose offices are now banned in Canada) and China.

Nor should it be lost on anyone that the emerging consensus is that Harris’s loss is largely the result of a collapsing US information ecosystem, with Trump voters marinating in low-quality information sources. The actual state of the economy or society doesn’t matter if people don’t hear about it.

In thrall to fears of government tyranny and the digital authoritarian boogeyman, they leave completely untouched fundamental questions of corporate ownership, control and purpose.

US communication companies have always been extensions of government power and influence. As Trump will be effectively immunized against prosecution for illegal acts committed while in office, we have to expect he will pressure US social media and search companies to interfere in the upcoming Canadian federal election. Musk has all but promised to do so, tweeting of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, “He will be gone.”

This is the actual authoritarian threat to Canada: foreign interference in our politics via biased platforms; foreign, authoritarian control over our essential information infrastructure; and the authoritarianism-enabling effects of disinformation along the same lines witnessed in the United States, driven in part by things such as Meta’s continued Canadian news blockade. And at its heart, unaccountable companies and foreign politicians regulating Canadians’ lives for their purposes, not ours.

While Canada should have been passing legislation placing these companies under strict controls, befitting their status as essential digital infrastructure, we’ve been practising digital Maginot politics. From the very start, the federal government had to respond to persistent worries from prominent academics and activists, as well as from the opposition Conservative Party, about incipient authoritarianism that veered at times into paranoid visions of “digital totalitarianism” and unhinged comparisons with Soviet Russia and Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels.

Birthed in this hostile environment, the government’s digital policy suite (the Online Streaming Act, the Online News Act and the proposed Online Harms Act) have been judged primarily on whether they were weak enough to keep the government from, somehow, sliding into authoritarianism or worse.

As a result, our laws are far too weak to tackle the now obviously existential problems of political interference and disinformation. In thrall to fears of government tyranny and the digital authoritarian boogeyman, they leave completely untouched fundamental questions of corporate ownership, control and purpose that are the essence of structural and political power.

What’s needed now — if we still have time — is what was always needed: online intermediaries firmly embedded in Canadian society, reflecting Canadian interests, values and desires.

Achieving them would include regulating the data-driven surveillance business model that drives many of big tech’s harmful tendencies; setting strong, enforceable direct regulation and government-set standards for social media, messaging services and search; establishing must-carry requirements for Canadian news; substantive revenue sharing between internet intermediaries and legitimate news sources; instituting online harms rules that cover all Canadians, not just children; and mandating independent dispute-resolution processes. Re-examining ownership standards, including the need for public or non-profit ownership of these de facto public utilities, and reconsidering the appropriateness of US ownership of structurally significant online intermediaries, would also help a lot.

It’s tragic. So many activists, scholars and politicians spent the past two decades worrying about how government regulation of the internet itself could lead to digital authoritarianism. Now authoritarianism is on our doorstep, in large part thanks to the efforts of so many to make the very idea of government digital regulation not just unpalatable but a political anathema. The bill has come due.