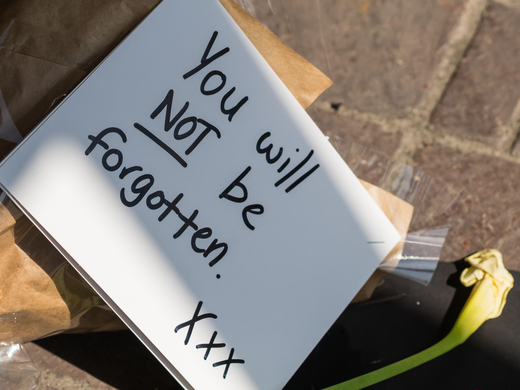

When I heard the news that Paul Pelosi, the husband of the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, had been struck on the head with a hammer in his home by a male assailant, my first reaction was dismay. But I was not surprised. On social media, Nancy Pelosi has long been the target of conspiratorial thinking, misogyny and violent anti-Pelosi memes. She has long been vilified by right-wing groups and Republican Party politicians, making her a top target of negative comments and threats online. The man accused in the attack, David DePape, had ties to QAnon, posted antisemitic, racist and transphobic content online and was determined to hurt Speaker Pelosi, who was on his “target list,” according to the grand jury indictment. He even told the police that he wanted to hold the congresswoman hostage and break her kneecaps; carrying out a life-threatening attack on someone she loves was every bit as wounding.

Unquestionably, the internet has given women around the world a new space in which to speak out. It has allowed access to the ideas of women, including women from marginalized groups, and been a power vehicle for social justice activism.

But the disturbing flip side is that there is a clear continuum between offline and online misogyny and xenophobia. For example, Troll Patrol, a 2018 Amnesty International and Element AI project, showed that the abusive messages that female politicians and journalists receive online are a reflection of the misogyny, sexism and gender stereotypes that women face in society. As Lucina Di Meco and Kristina Wilfore explain in a report drafted for the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies, misogynistic content “is designed to tap into emotionally loaded implicit bias against women in power” and “fake stories steeped in misogyny and portraying women as stupid, untrustworthy, and sexualized” are meant to silence women. Worse, the business model of social media platforms has been weaponized against women, so that gender-based violence has not only found new soil but been amplified through algorithms that promote inflammatory content and disinformation.

There are two important misconceptions about online hate. One is that it stays online. The second is that it only concerns its target. In truth, online hate and disinformation against women are systemic, institutional and global ills, and concern us all. Last week’s International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women marked the beginning of a 16-day campaign to unite to act against gender-based violence. We should take this moment to make it clear that social media has become an additional tool to perpetuate the long-existing culture of silencing and disempowering women.

As national and international politics became more polarized over the past decade, gender, politics and the internet started to intersect. One of the first instances of this was Gamergate, a year-long campaign of harassment and misogyny against game developer Zoe Quinn, a woman who sought to change the culture of an industry known for its depiction of violence and sexist portrayals of women. The movement rapidly evolved into a large-scale right-wing backlash against feminism. In a recent interview about Meme Wars, her new book co-written with Emily Dreyfuss and Brian Friedberg, Harvard Kennedy School researcher Joan Donovan argued Gamergate marked a shift in our understanding of social media because those involved felt a sense of community and instantaneous reward as they saw women shut down accounts or leave jobs because of the constant online harassment.

Gendered disinformation and violence against women online have become a reality across the globe.

Women are the target of “gendered disinformation,” which Lucina Di Meco describes as “the spread of deceptive or inaccurate information and images against women political leaders, journalists and female public figures.” According to a new US-based report by the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT), “as more women have sought political representation by running for elected office, we have seen demonstrated increases in online harassment and abuse, including targeted mis- and disinformation campaigns.” Looking at the 2020 US elections, the CDT found that candidates who were women of colour were more likely than other groups to be targeted by these campaigns. Furthermore, messages were more likely to focus on their identity. The aim of gendered disinformation is to discourage women from participating in public and civic life, but women do not necessarily have to be politicians to be targeted. At the January 6 hearings, Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss, two Black female poll workers from Georgia, explained how they became the target of conspiracy theories by the Trump campaign and its supporters and went into hiding as a result. This case is a proof of the damage that online hate can have not only on individuals but on democracy as well: who would want to be a poll worker in this environment?

Gendered disinformation and violence against women online have become a reality across the globe. In the Philippines, journalist Maria Ressa has long been the target of bots, astroturfing, hate messages and fake accounts for trying to shine light on the undemocratic and corrupted nature of President Rodrigo Duterte’s administration. She is attacked both as a journalist and as a woman. In Brazil, investigative journalist Patrícia Campos Mello faced an aggressive online harassment campaign following her reporting on then presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro. The messages contained sexual slurs, rape threats and slanderous videos accusing her of being a prostitute.

Things tend to be worse in authoritarian countries. A new study by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute shows how coordinated information operations against women of Asian descent living in democracies have become widespread and increasingly abusive and part of the Chinese Communist Party’s playbook to silence female journalists who dare to criticize the Chinese government. Chinese-state affiliated accounts use multi-faceted tactics to intimidate women through constant misogynistic, homophobic, sexualized and racist content. Women who become the target of these campaigns are described as traitors and liars and sent highly sexualized imagery and physical threats.

Indeed, the Chinese government, with the help of Chinese tech companies and ultra-nationalist online communities, has used sophisticated tactics to retaliate against China’s growing feminist movements, which it perceives as threatening its authority. Women who used social media to speak out about sexual harassment and gender inequalities have seen their posts removed or accounts shut down. The Chinese Communist Party encouraged and amplified the misogynistic messages of ultra-nationalist users against feminist movements, thereby also fanning more nationalist sentiments.

In Saudi Arabia, Freedom House reports, “severe gender-based repression … results in women featuring more prominently in the country’s transnational repression campaign than in other cases.” Existing discrimination against women is therefore replicated online. Prince Mohammed bin Salman has gone after women who led online campaigns demanding the right to drive, and women who spoke out on social media about sexual harassment were met with a barrage of threats and told that they could face fines and prison sentence for “spreading rumors.”

Fixing social media will not eradicate the root causes of violence against women but we should aim at least to prevent violence from being perpetuated on these platforms.

Tech leaders have failed to make women safe on their platforms. The future of Twitter is uncertain, but Elon Musk’s absolutist vision of freedom of expression is unlikely to benefit users who already face hate, misogyny, xenophobia and other forms of oppression. Musk’s idea of a “common digital town square” does not have the public interest of users, women in particular, at heart. Musk himself tweeted baseless conspiracy theories about Nancy Pelosi’s husband days after he was attacked and in response to a tweet posted by Hillary Clinton. When the new CEO of Twitter is engaged in disinformation, there is a problem.

But as Wired recently argued, our governments have also failed to make users safe by “ced[ing] our public sphere to centralized, advertising-driven companies controlled by a few men.” However, addressing the technological aspects will not be enough. Fixing social media will not eradicate the root causes of violence against women but we should aim at least to prevent violence from being perpetuated on these platforms. Democratic governments must take appropriate steps to combat online violence against women.

The internet has given us access to the voices of women who needed to be heard. The International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women should serve as a reminder that we must make sure that social media companies don’t build barriers to the advancement of women’s rights.