In the nineteenth century, government officials came to understand that steel would be essential to both economic growth and national security. Accordingly, several countries devised policies that could not only sustain local production, but also prevent foreign producers from competing in domestic markets.

By the 1950s, these countries collectively were producing too much steel. Manufacturers substituted products such as plastics or aluminum. Nonetheless, policy makers in Japan, India, the United States and the European Union were determined to maintain domestic capacity, because steel remained essential for military hardware such as tanks, submarines and machine guns, as well as for housing.

Surprisingly, even today, governments keep investing in steel, even as demand for it continues to shrink. In 2023, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) predicted that overcapacity would worsen, causing difficult market conditions and exacerbating climate change.

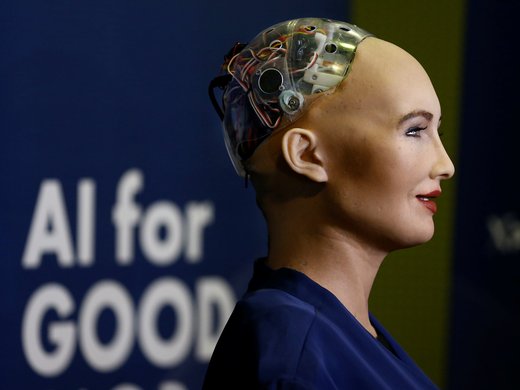

Is artificial intelligence (AI) the new steel?

Of course, steel and AI could not be more different. Steel is a component — a manufactured alloy used to create a wide range of products, from tanks to toasters. In contrast, AI is a machine-based system that infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments.

Individuals, governments and firms are using AI to improve productivity, enhance human welfare and help address complex challenges such as climate change. Moreover, in contrast with steel, many economists view AI as a general-purpose technology that can stimulate both economic growth and innovation. Hence, policy makers must ensure domestic capacity.

However, many government officials also already see AI as a critical technology essential to both national security and economic progress. According to a 2023 review of policies and programs reported to the OECD, more than 60 countries are using taxpayer dollars to create, disseminate or do research on AI. That’s a lot of AI.

Policy makers in the European Union, Germany, Japan, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom and the United States have recently announced huge public investments in AI (these investments follow large private sector investments). The European Union has provided US$1 billion in funding each year for AI capacity building since 2018. In March 2024, the Saudi government announced it would use some $40 billion of its US$900 billion sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund, to invest in AI at home and abroad. Such sums would make the Saudis the largest investors in AI by far.

At the national level, these investments are understandable. But collectively, they could lead to overcapacity — a situation where the supply of AI exceeds demand.

Such overcapacity creates pitfalls in addition to the already well-known risks of AI, such as bias or inaccuracy. As nations seek to sustain domestic AI competitiveness and market share, for example, some might “dump” excess capacity. That could make it easier for criminal elements or rogue agents to acquire the technology. Here, overcapacity could lead to political instability.

Moreover, AI producers need huge sums of capital to design, develop and deploy these systems. To attract and sustain such investment, some firms or governments may choose to disregard guardrails — strategies designed to limit potential negative effects. Here, overcapacity may be correlated with untrustworthy or irresponsible AI.

Furthermore, as they compete with other nations, policy makers may hoard data or limit access to technologies, making it harder to cooperatively use AI to advance knowledge or to collectively address wicked problems such as climate change. Here, overcapacity may be correlated with a lack of cooperation on the uses of AI.

Finally, there is an opportunity cost to over-investment in AI. Without deliberate intent, such investment may come at the expense of other technologies and approaches to analyzing large pools of data.

Overcapacity is a normal problem in national and international economies. At times, supply outstrips demand.

But when various governments intervene to create and sustain capacity, as they have done with steel and may now be doing with AI, governments will struggle to address the global spillovers.

Policy makers should begin talking about this potential risk at existing important international venues such as the G7, the G20 and the United Nations.

This piece first appeared in Fortune.