In his 1956 novella, The Minority Report, American author Philip K. Dick describes a world where mutant psychics aid police to stop crimes before they occur. Seven decades later, “precrime prediction” is no longer entirely fictional thinking, as some law enforcement agencies are betting artificial intelligence (AI) can manifest Dick’s fantasy into reality.

Police departments worldwide are already embracing AI-powered tools to advance the field of predictive policing. And some authoritarian regimes have openly declared their intent to use these technologies to eliminate crime altogether.

This is especially true as public budgets are being stretched thin and complex threats are proliferating. Political violence is on the rise. Terrorist groups, such as the Islamic State, are reanimating in the security voids created by great-power competition. Transnational criminal organizations and human trafficking networks are growing ever more sophisticated. And the quantifiable harm from the cybercrime industry is now equivalent to the third-largest economy in the world.

It’s unsurprising that predictive policing holds an allure for officials in liberal democracies as well. But the promise of these technologies masks a series of profound ethical dilemmas. Human rights experts have already warned of flaws inherent in them and the risks their use poses to individual liberties. Without adequate protections or guardrails in place, even in the hands of the well-meaning, the technologies and practices involved could open the door to a dystopian future of ubiquitous state surveillance. And it is not hard to imagine how, in the hands of vengeful and paranoid actors in power, these same predictive tools could be used to quash even the most nascent opposition.

Predictive Technology in Action

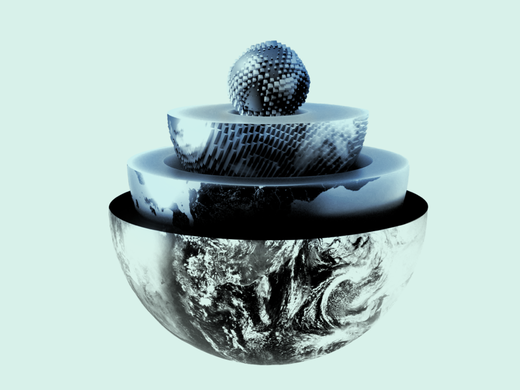

At its core, predictive policing involves the use of algorithms to forecast when and where crimes are likely to occur. These predictions are generated by machine-learning models sifting through reams of historical crime data. Woven into this process are various other inputs, including data points drawn from social media content, closed-circuit television footage, biometrics, demographic indicators and socio-economic metrics — even weather and traffic patterns.

Advocates claim using these tools isn’t just a matter of data-driven efficiency but also a way to overcome the human biases and limitations that plague traditional policing.

Predictive policing generally falls into two different categories: location-based and person-based. The former harnesses big data to pinpoint particular sites or specific time windows where crime is likely to occur. In contrast, person-based methods use arrest histories and established theories of criminal behaviour to identify individuals or groups with a higher probability of either committing crimes or becoming victims of them. Both approaches have been piloted in American cities and beyond, and date back to the early 2010s.

Advocates claim using these tools isn’t just a matter of data-driven efficiency but also a way to overcome the human biases and limitations that plague traditional policing. The idea is that computer modelling provides insights into criminality that are superior to officers’ guesswork. The desired outcome is to optimize resource efficiency and stop harmful activity before it occurs or escalates, rendering police operations safer and less costly. Research from the McKinsey Global Institute suggests that integrating AI into law enforcement might lower urban crime rates by 30 to 40 percent. Emergency response times may similarly be slashed by up to a third.

And indeed, there have already been some notable real-world success stories.

Marinus Analytics, a company founded by women and spun out of Carnegie Mellon University’s Robotics Institute, has successfully combined AI, machine learning, predictive models and geospatial analysis to track down missing persons in the United States who have disappeared into sex trafficking rings. Ironside, a data solutions firm, says its predictive policing model developed for the city of Manchester, New Hampshire, reduced the impacts of crime by 28 percent within the first five weeks of deployment.

Intelligent police tools based on deep learning have been utilized by local governments in Japan since first being adopted prior to the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. Especially touted is the country’s Crime Nabi system, developed by a private sector start-up. Authorities say simulations show it is over 50 percent more effective than conventional policing tactics in identifying high-risk areas. The system has since been shared with state military and police forces in Latin America — a region suffering from some of the world’s highest rates of homicide and violent crime. In the Brazilian city of Belo Horizonte, for example, a pilot project using Crime Nabi sharply curtailed the theft of metal cables from construction sites. While not the most spectacular use case, this is the exact type of low-level criminality that bleeds police resources dry, while also stifling economic development.

More recently, on April 2, the government in the Indian state of Maharashtra, home to the financial hub of Mumbai, approved an expansion of its MARVEL system. Created in 2024, MARVEL permits the sharing of police data with both a state-owned AI firm and a private sector start-up to autogenerate case files, furnish insights and enhance the intelligence capabilities of police units. Britain’s Ministry of Justice is also developing its own so-called murder prediction tool. According to freedom of information requests filed by civil campaigners, it will draw on, among other data sets, individual markers of mental health, addiction, suicide and self-harm.

Alongside the rising amount of experimentation, meanwhile, steady progressions in technology are also bound to drive evolution in predictive policing models.

Google last December unveiled an upgrade to its visual-language model, PaliGemma. This advance will soon make it much easier for generative AI programs to assess video content, such as surveillance footage. Huge leaps are being made in the field of mind-reading neurotechnology and in the development of commercial spyware tools. Mergers and acquisitions within the police tech industry are also consolidating start-ups into larger entities capable of providing law enforcement agencies with a full suite of cutting-edge options.

Law Enforcement Re-engineered

None of these advancements come without risk. Human rights groups and digital watchdog organizations have labelled predictive policing tools as corrosive to individual liberties. Rather than upholding law and order, critics warn advanced tech will promote discrimination and harassment, discourage free assembly and enable arbitrary detention. A lack of accountability around their use could arise from obstruction by police unions, which have historically resisted efforts at oversight and reform. The consequences for open societies could be grim.

Liberalist fears over predictive policing also partly reflect how law enforcement is already being remade for the twenty-first century elsewhere. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is among a vanguard of autocracies leading these efforts. The main catalyst for this came more than a decade ago, as popular uprisings during the Arab Spring rattled Gulf monarchies whose existence depends on preserving rigid, hierarchical forms of social organization.

In early 2023, The New York Times reported on a police technology conference in Dubai where “sentiment analysis software” — used to algorithmically infer someone’s mood based on their facial expressions — was marketed alongside Israeli hacking tools and Chinese visual recognition cameras. Host officials promoted Emirati machine-learning models they boasted could predict some crimes with 68 percent accuracy: “Nowadays, the police force, they don’t think about the guns or weapons that they’re carrying,” the head of AI for Dubai’s police department told reporters. “You’re looking for the tools, the technology.”

But while the UAE has become a leader in embracing emerging biotechnologies for law enforcement, China has proven even more ambitious in integrating surveillance and predictive technologies for population control.

Later that same year, the crown prince of Dubai, Sheikh Hamdan bin Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, attended an event to launch the city’s Genome Centre, housed within the law enforcement’s General Department of Forensic Science and Criminology. The facility falls under the UAE’s national genomics strategy and was created to support police work through advanced testing of forensic identification and genetics. The crown prince was also briefed on Dubai’s so-called “brain fingerprint” system. Already used in prosecutions, this advanced system is said to generate insights into a suspect’s memory upon exposing them to crime scene images or materials.

But while the UAE has become a leader in embracing emerging biotechnologies for law enforcement, China has proven even more ambitious in integrating surveillance and predictive technologies for population control. The country deploys sophisticated AI tools across an array of applications — from managing traffic violations to monitoring and suppressing ethnic and religious minorities. The Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), deployed in China’s western Xinjiang province — home to most of the country’s Muslims — remains Beijing’s most notorious example of mass surveillance. Blending data on features such as facial recognition and travel patterns to religiosity and even electricity usage rates, the IJOP flags so-called “pre-criminal” activity and suspicious behaviour as defined by its algorithms. Empowered by the system, local authorities are permitted to detain individuals without them ever having committed a crime.

Much of this Chinese tech has already been proliferating across the world, as nations — in the Global South in particular — have been playing both sides of the great-power competition. Prior to the second Trump administration, the United States was considered the guarantor of international security. China, on the other hand, has increasingly been viewed as a master architect of domestic security, with Beijing’s strict public safety model exported internationally through its Digital Silk Road infrastructure scheme. Surveillance systems manufactured by Chinese firms such as Hikvision and Dahua have been sold to dozens of countries across Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia.

But there’s growing enthusiasm among law enforcement agencies in liberal democracies, too, for predictive policing tools.

Accountability Needed

Internal records from the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), reported in March by The Intercept, show that between October 2023 and April 2024 city law enforcement officials were alerted by an American social media surveillance company, Dataminr, to more than 50 different protests condemning Israel’s war on Gaza. At least a dozen of these notifications were sent out before any demonstration even occurred. As for Dataminr, it previously made a name for itself by helping the LAPD monitor communities of colour. Police departments across the United States have also been criticized by digital rights groups for running DNA-generated three-dimensional models through facial recognition tools in attempts to predict a suspect’s appearance.

In Spain, the country’s VioGén system — co-developed by law enforcement and academic specialists — is meant to help protect women by enabling police to prevent recurring domestic violence. When a victim first reports an incident, police ask them a standardized set of dozens of questions about their situation. These include questions about the abuser’s access to weapons, mental health and their current relationship status. The information is fed into a file created in the VioGén database that the system then uses to forecast the likelihood of a repeat incident. However, the system has recently come under intense scrutiny after a woman assigned only a medium risk of re-victimization by an ex-partner was found dead in a suspected arson attack just weeks after she went to police.

But amid the development and adoption of these systems, there are some efforts emerging within liberal democracies to regulate them.

In Europe, Article 5 of the EU Artificial Intelligence Act, in effect since February 2025, prohibits the marketing or use of AI systems to predict the probability that someone will commit a crime. However, there are many exceptions to this prohibition, including for major crimes, such as acts of terrorism, murder, rape, armed robbery, hostage taking, war crimes, kidnapping and human trafficking, among others.

A report from the Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto examining algorithmic policing in Canada offers more than a dozen policy suggestions to serve as guardrails. For example, the researchers say that before AI systems are ever deployed by a police force, officials should engage in extensive consultations with independent experts and vulnerable and marginalized communities. As well, a judge must always sign off on the use of such systems. Further, there should be maximum transparency and disclosure when such systems are used — including around model training data. Regular audits of decision-making procedures should be mandated, and technology subject to continuous third-party testing. In addition, individuals should always retain the ability to verify and correct the accuracy of personal information stored in police databases.

Threats to individual and public safety will only become more complex over time. And it’s understandable that law enforcement agencies everywhere desire new tools to make their work more effective. The key with predictive policing, then, will be to ensure that the relatively small body of evidence around its benefits isn’t harnessed by law makers and law enforcement alike as reason to dismiss its very real risks.