The multilateral architecture created after the Second World War provided a set of rules that helped to settle, or at least limit, conflicts.

In the past five years, that rules-based international order has suffered three major blows.

The first of these was Donald Trump’s “America First” policy, which turned the United States’ role on its head. From being the main designer of multilateral architecture, America became its main challenger.

Second, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a “family comes first” reaction. Many governments “instinctively” repressed exports of personal protective equipment and medical supplies to ensure domestic supply. Once a source of resilience, economic interdependence turned into a challenge to national security.

The third blow was Vladimir Putin’s use of military might in 2022 to again try to redraw Russia’s borders (following its invasion of Crimea in 2014). Western countries rapidly imposed tough sanctions and championed a UN General Assembly resolution condemning Russia’s breach of the UN Charter (chapter VII); yet 82 countries representing more than half of the world’s population (and about 25 percent of global GDP and 20 percent of exports), either abstained or took sides with Russia.

The polarization of the world pitches Western-styled democracies championing progressive values and human rights against autocracies championing conservative values and economic advancement as a precondition for human rights.

Conflicts have multiplied, and multilateral institutions are not in good shape to contain perceived challenges to national security. This weakening of the system could precipitate post–Second World War institutional architecture into decay, and eventually irrelevance. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Trade Organization (WTO), the two multilateral institutions where rules to regulate trade and capital movements are negotiated, would not be spared.

Both the IMF and the WTO need symmetrical reforms. A “grand bargain” might be the approach that could rejuvenate trust in their capacity to preserve economic interdependence.

Macro-trend: Geopolitical Rivalry Is Trumping Economic Logic

Favoring the “friend-shoring” of supply chains to a large number of trusted countries, so we can continue to securely extend market access, will lower the risks to our economy as well as to our trusted trade partners.

Trade between countries with different endowments and wages entails economic benefits for consumers and businesses and has pulled millions out of poverty. A significant part of trade is already delivered digitally, as trans-border data flows have been growing at staggering rates.

Information and communication technologies have knitted a tightly interconnected world. Yet, politics are working in the opposite direction. Economic interdependence is regarded as a source of vulnerability, and geographical and political proximity are portrayed as remedies to foster resilience of supply chains.

Globalization worked as a “gigantic shock absorber,” but nearshoring could make the economy more vulnerable to regional hazards, and building up stocks to increase resilience will also increase costs and could compound the effects of local economic cycles. Stockpiling during booms and fire sales during busts could deepen recessions and hinder monetary and fiscal counter-cyclical efforts. And then, Western financial markets stand to lose if the US dollar loses dominance as the principal means to settle trade. Indeed, efforts to decouple China are already rendering results, as the People’s Bank of China has started trimming its holdings of US Treasury bonds.

A New World: Choose Your Camp

A serious risk to the medium-term outlook is that the war in Ukraine will contribute to fragmentation of the world economy into geopolitical blocs with distinct technology standards, cross-border payment systems, and reserve currencies.

China’s “no-limits partnership” with Russia is inflaming the West’s anti-China sentiment, which in turn reinforces Beijing’s perception that the United States wants to suppress China’s international influence by confining countries to adopting America’s own standards and rules.

Mistrust is growing. China, the European Union and the United States are all aiming at reducing their reliance on “strategic” imports and, following Russia’s invasion to Ukraine, it is no longer possible to assume that a major conflict is unlikely.

Each camp is advancing negotiations that could lead to a fractured new institutional framework. The United States is promoting a “China-less” Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, while China is sponsoring an “America-less” Global Security Initiative. Competing institutional frameworks could result in two (or more) incompatible, if not hostile, sets of rules.

“Flirting” with the rival camps could extract benefits. Indeed, China and the United States are already competing in the courting of developing countries. China’s Belt and Road initiative is still the world’s largest source of bilateral development credit, but the United States is ramping up its international Development Finance Corporation, and on June 26, the Group of Seven launched a counterbalancing initiative, the Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment.

However, the “flirting” could go on only up to a point. The deepening of the geopolitical divide and the multiplication of conflicts would eventually force most developing countries to pick sides. That would be lethal for the current multilateral architecture. It would galvanize international polarization and it would resonate in domestic politics, wrong-footing moderate political parties and putting at risk democratic dissent.

Time for a Grand Bargain?

In a world fractured in distinct spheres of influence, multilateral institutions could languish into irrelevance, leaving most countries subject to raw-power politics.

This is not yet unavoidable if a coalition of middle-powers stands to buttress the two multilateral institutions with responsibilities on trade and capital movements. A daunting challenge, yet the IMF and the WTO need symmetrical reforms.

At the IMF, large emerging markets have been (quite unsuccessfully) striving to augment their responsibilities in proportion to their increased weight in the world economy (read: pay larger quotas). At the WTO, the picture is exactly the opposite. It is developed countries that have been (unsuccessfully) trying to persuade large emerging markets to give up their “special and differential” (S&D) treatment and assume responsibilities concomitant with their increased weight in world trade.

The WTO has 164 members. About two-thirds of these members claim to be “developing” and therefore entitled to S&D treatment, which are provisions meant to give them longer periods to introduce less ambitious tariff reductions. Imposing “lighter” obligations on countries with fewer fiscal resources makes a lot of sense. Opening markets implies that uncompetitive industries may close businesses faster than the economy’s capacity to reabsorb the displaced labour and capital. Countries need fiscal resources to cushion the transit. Giving developing countries more time to introduce less ambitious tariff reductions allows their governments to round up support for trade liberalization.

Yet, at the WTO any country can claim to be “developing” and stay in that category for as long it wishes. There are no graduation criteria and no rules to tell when a developing country is ready to compete on an equal footing in the world marketplace. Large emerging market economies (EMEs), as those sitting at the Group of Twenty, have very competitive exporting industries, yet they still cling to the S&D “crutch.” This prejudices countries that are truly disadvantaged, as developed countries strive to water down the S&D “benefits.” It also undermines the WTO’s capacity to update its rules and pursue or host new rounds of trade liberalization.

The picture at the IMF is similar, but in the opposite sense. In Washington, it is the developed camp that staunchly resists allowing EMEs to increase their quotas and assume more responsibilities in conducting the Fund’s business.

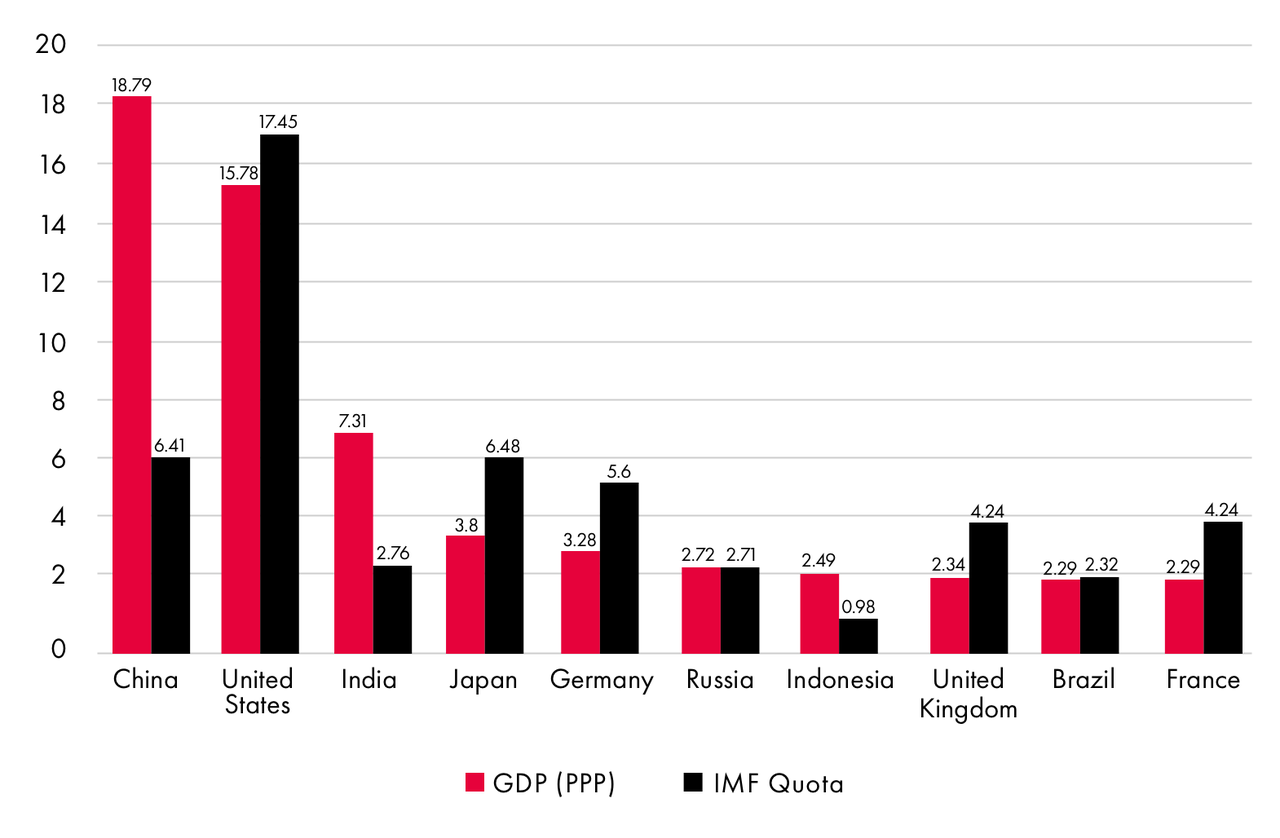

The key determinants of the voting power in IMF decisions are IMF quotas. Larger economies should contribute larger quotas to the Fund’s pool of financial resources. However, quotas are still calculated using an arcane formula that allocates exaggerated influence to “advanced” economies (IMF jargon for “developed” countries), notably its European members, who are able to block periodic quota reviews. (All of the IMF’s directors since its establishment have been Europeans.)

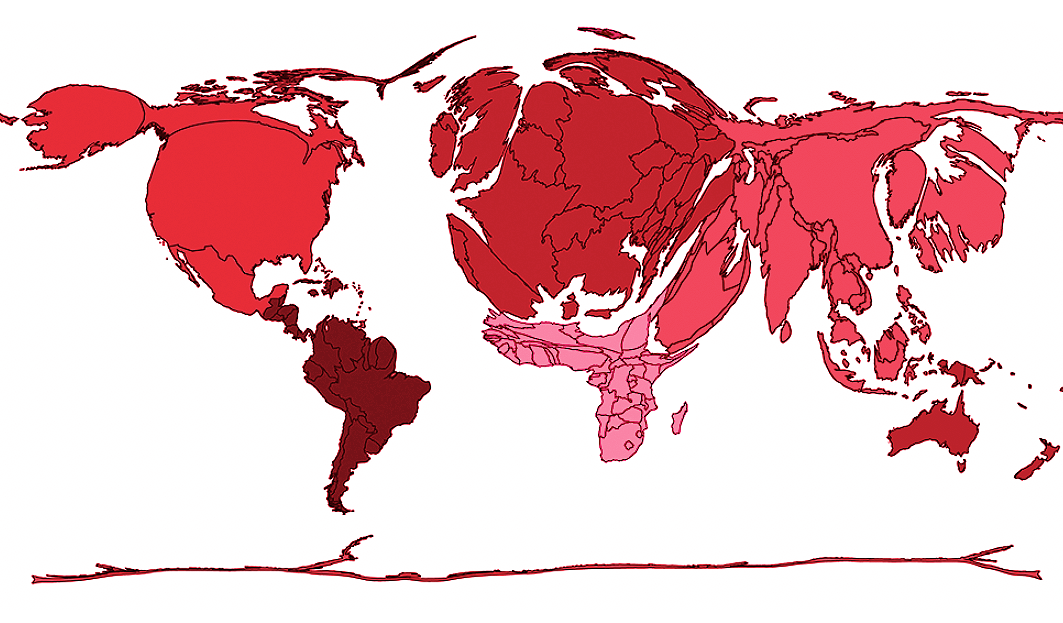

The Fund reviews its quotas every five years. The fifteenth and most recent review (in 2020) concluded with no agreement to increase quotas (hence no redistribution of relative sway was possible). The sixteenth review (ongoing) should be completed no later than December 15, 2023. Each review is an opportunity to increase contributions to the Fund’s pool of resources, redistributing relative quota shares in favour of the most dynamic economies, predominantly large EMEs. However, the “developed” camp has sufficient influence to prevent this from happening, as any changes in quotas must be approved by an 85 percent majority of the total voting power. Hence, despite Asia’s increased weight in the world economy, the IMF still remains a North Atlantic–driven institution (Figure 1).

Figure 1: How the IMF World Looks According to Quota Distribution

China and India, whose IMF quotas only represent a fraction of their share in the world’s output, are the IMF’s most under-represented EMEs and WTO’s largest “developing countries” (Figure 2).

Figure 2: World GDP Share versus IMF Quotas

Conclusion

The post-Second World War economic growth and relative peace owe much to the world’s multilateral architecture, and particularly to the two institutions responsible for liberalizing trade and regulating capital movements. However, the IMF and the WTO need to come to terms with reality. Taken separately, neither the WTO’s nor the IMF’s agenda is broad enough to allow for reforms that could be regarded as “balanced” by the competing camps.

Developed countries should allow the most dynamic economies, in particular China and India, to increase their IMF quotas, which would prop up the IMF’s legitimacy as a truly universal institution, and also reinforce its core capital at a moment when the “global economy faces its greatest challenge in decades.” On the other side of the Atlantic, China and India, as the two largest “developing” economies, should assume full trade responsibilities and cooperate in ensuring that WTO’s S&D treatment provides tangible benefits to those countries that need it most.

Fair IMF representation, in exchange for assuming full trade responsibilities at the WTO: symmetrical reforms could balance the deal, making it politically feasible. Putting things straight on both sides of the Atlantic would breathe new hope in multilateralism.