In the past few decades, data has emerged as an invaluable asset, offering the promise of shaping our collective future through informed decision making and transformative solutions. Its potential spans crucial domains such as climate action, health care and economic development, where data-driven approaches hold the key to unlocking progress for the greater good. However, the use of data for public good1 is not without its hurdles. While it fuels innovation and progress, it also presents challenges, such as widening disparities and privacy concerns. Robust legal frameworks and ethical guidelines governing data collection, storage and accessibility need to be established in order to achieve a balance between advancing shared interests and safeguarding individual rights.

Governments play a pivotal role in shaping this framework, enacting clear regulations, adopting international standards and establishing oversight mechanisms. Effective data governance, particularly concerning government-held data, ensures accessibility while safeguarding privacy. Moreover, despite the increasing attention to artificial intelligence (AI), the fundamental role of data governance in this landscape is often overlooked, as stated by Stefaan G. Verhulst and Friederike Schüür (2023). AI governance relies inherently on the principles and practices of data governance, and neglecting this synergy leads to fragmented approaches and missed opportunities for collaboration.

The March 2024 UN General Assembly draft resolution A/78/L.492 emphasizes the critical role of data and data governance in advancing “safe, secure and trustworthy” AI systems (UN General Assembly 2024), which are fundamental for driving sustainable development globally. Acknowledging data as the cornerstone for both developing and operating AI systems, the resolution3 urges the adoption of fair, inclusive, responsible and effective data governance practices. It calls for enhancing data generation, accessibility and infrastructure while maximizing the utilization of digital public goods. Furthermore, member states are urged to exchange best practices on data governance and to foster robust international cooperation, collaboration and assistance efforts.

In essence, data governance emerges not only as a mechanism for responsible data management but also as a tool for promoting positive societal change and inclusive development.

Following all those ideas, failure in data governance may result in AI systems falling short of legal and regulatory compliance, posing risks to data integrity and privacy. This underscores the importance of establishing clear frameworks, particularly for public data. According to the 2021 World Development Report: Data for Better Lives, unlocking the full potential of data for development requires the establishment of a comprehensive national data system supported by data governance frameworks, and addressing factors such as data quality, technical standards and transparent processes (World Bank 2021).

This essay explores the landscape of public data governance, drawing insights from the first edition of the Global Data Barometer (GDB).4 It delves into the complexities, challenges and opportunities inherent in this domain, emphasizing the potential of data governance as a catalyst for positive societal change and inclusive development.

A Global Overview of Data Governance

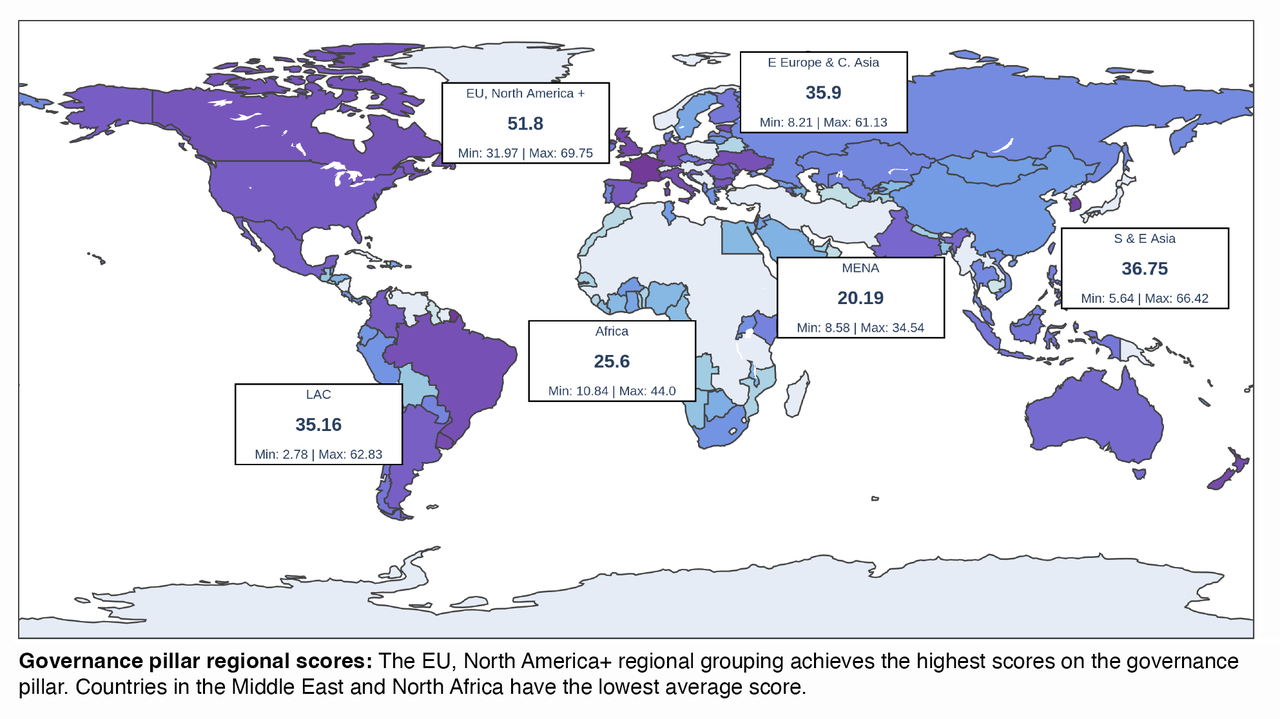

Effective data governance plays a paramount role in ensuring the reliability and integrity of data throughout its life cycle. At its core, data governance entails maintaining high data quality and implementing robust data controls, which are crucial for training AI models and making informed decisions. In essence, data governance emerges not only as a mechanism for responsible data management but also as a tool for promoting positive societal change and inclusive development. Ultimately, navigating the data governance landscape requires an approach that integrates legal frameworks, technological standards and collaborative efforts to ensure responsible and effective data management for the benefit of society and the ethical advancement of AI technologies (see Figure 1). This encompasses various key focus areas such as consistency, data integrity, security and standards compliance.

Figure 1: Governance Pillar Regional Scores

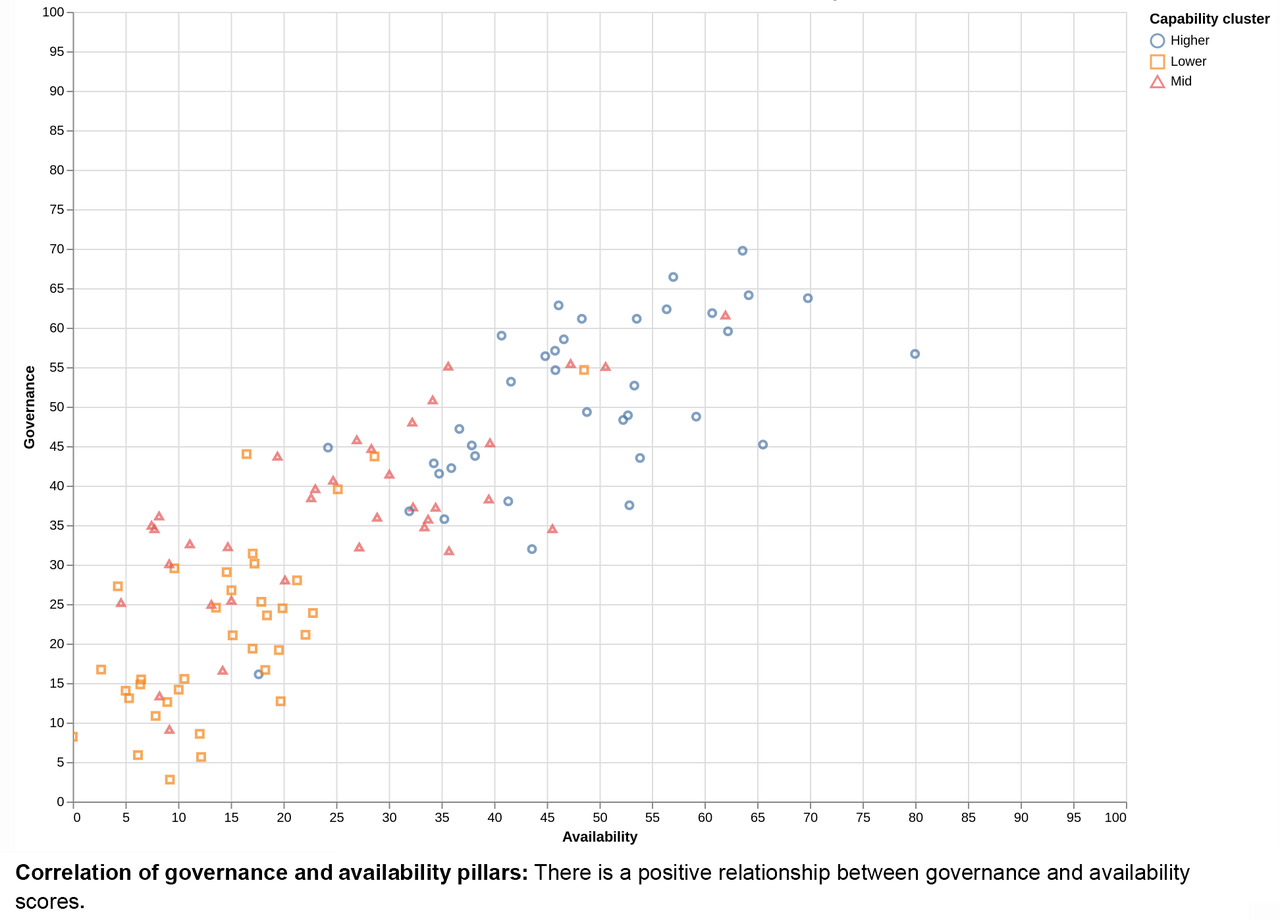

The significance of data governance is underscored by insights from the GDB. For example, the positive correlation between governance and public availability5 scores in the GDB (2022) highlights the essential role of robust data governance frameworks in making data readily available and fostering progress (see Figure 2). Thus, the correlation between laws mandating data publication and actual data availability is evident, yet disparities persist in the implementation of these requirements across various sectors, highlighting the existence of “implementation gaps” that warrant attention and remediation.

Figure 2: Correlation of Governance and Availability Pillars

The next section explores various challenges within the realm of data governance, including privacy concerns, open data policies and the dynamics of data sharing.

Navigating the Complexities: Challenges in Data Governance

The global landscape of data governance presents a nuanced picture, marked by both progress and challenges. While advancements have been made in establishing legal frameworks and data policies, significant hurdles remain.

Uneven Progress

According to the main findings of the first edition of the GDB, countries around the globe are increasingly recognizing the importance of safeguarding personal data through regulations. However, in some cases, these frameworks provide limited protections, primarily focusing on specific sectors rather than offering comprehensive coverage. There is therefore diversity in the implementation of data governance frameworks across countries, with many lacking comprehensive regulations. This creates a patchwork of data protection, privacy and sharing frameworks, which can hinder collaboration and potentially exacerbate existing inequalities.

In that sense, although 98 out of 109 surveyed countries by the GDB present some sort of data protection framework, only 46 percent of them boast robust data protection frameworks, leaving a significant portion of the global population vulnerable to data misuse and privacy violations. According to Keziah Munyao of the Local Development Research Institute, who provided an overview for Sub-Saharan Africa in the Global Report, “The fieldwork also identified gaps with respect to data protection or privacy standards in a number of countries, even where efforts are underway to promote wider data usage and openness. The absence of strong legal frameworks alongside new technological advancements seems to be a developing concern, particularly in countries where no frameworks exist to oversee the use of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI)” (GDB 2022, 74).

Balancing Privacy and Innovation

Balancing individual privacy rights with the vast potential of data sharing for innovation and the greater public good poses a multi-faceted challenge. Persistent concerns surrounding data collection, storage and utilization continue to evoke ethical and legal dilemmas, complicating the quest for a sustainable equilibrium. Following Uma Kalkar and Natalia González Alarcon (2023), the strategy that finds a balance between regulating and encouraging innovation considers both data protection and the advancement of data reuse.

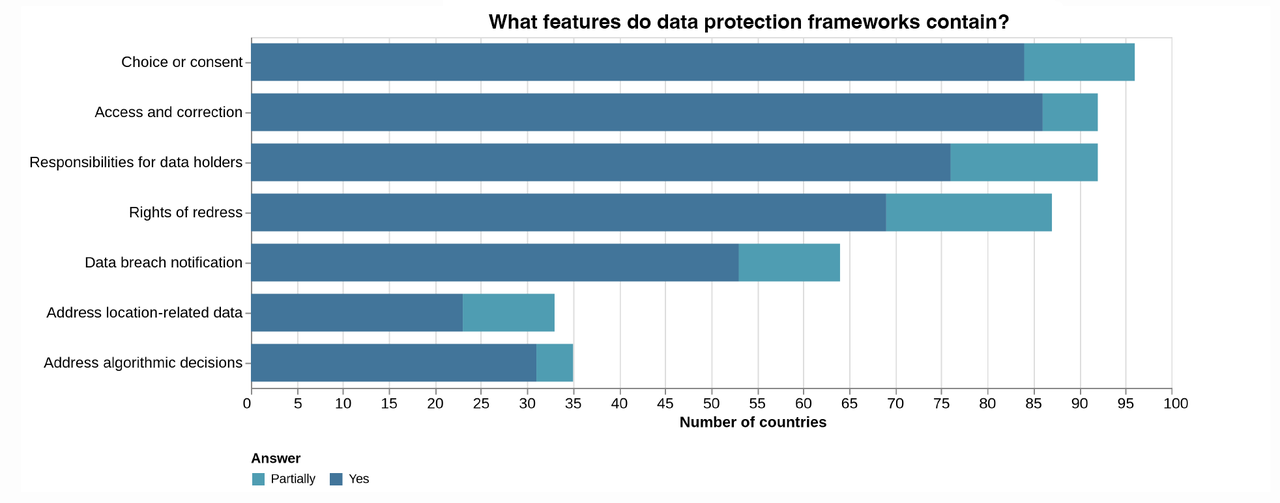

The journey toward establishing comprehensive data governance requires continual refinement and adaptability. Insights from the Global Report (GDB 2022) reveal a significant gap in data protection regulations across countries. Notably, while certain aspects are widely covered, 45.9 percent of nations lack robust provisions for data breach notifications, and 29.6 percent offer limited redress for harm caused by data misuse (ibid., 24). Moreover, only 23.5 percent of existing frameworks effectively address location data concerns, with a slightly higher percentage (31.6 percent) tackling issues related to algorithmic decision making (ibid.) (see Figure 3). Nevertheless, recent advancements in global standards6 underscore a commitment to tackling emerging challenges. Efforts are increasingly focused on improving breach notification protocols and recognizing the sensitivity of location data. In alignment with UN resolution A/78/L.49, safeguarding privacy and personal data integrity during AI system testing and evaluation is paramount.

Figure 3: Features in Data Protection

Untapped Potential of Open Data

Open data, when readily accessible and usable, can fuel innovation, empower individuals and foster transparency. In this context, the proliferation of open data policies emerges as a beacon of progress. The GDB Global Report identified 74 countries with open data policies, 30 of which have legally enforceable regulations (GDB 2022, 25). However, this potential remains largely untapped due to issues of standardization and interoperability (only 47.3 percent of policies address common data standards) (ibid.). Without consistent standards and seamless interoperability, open data initiatives struggle to achieve their full impact.

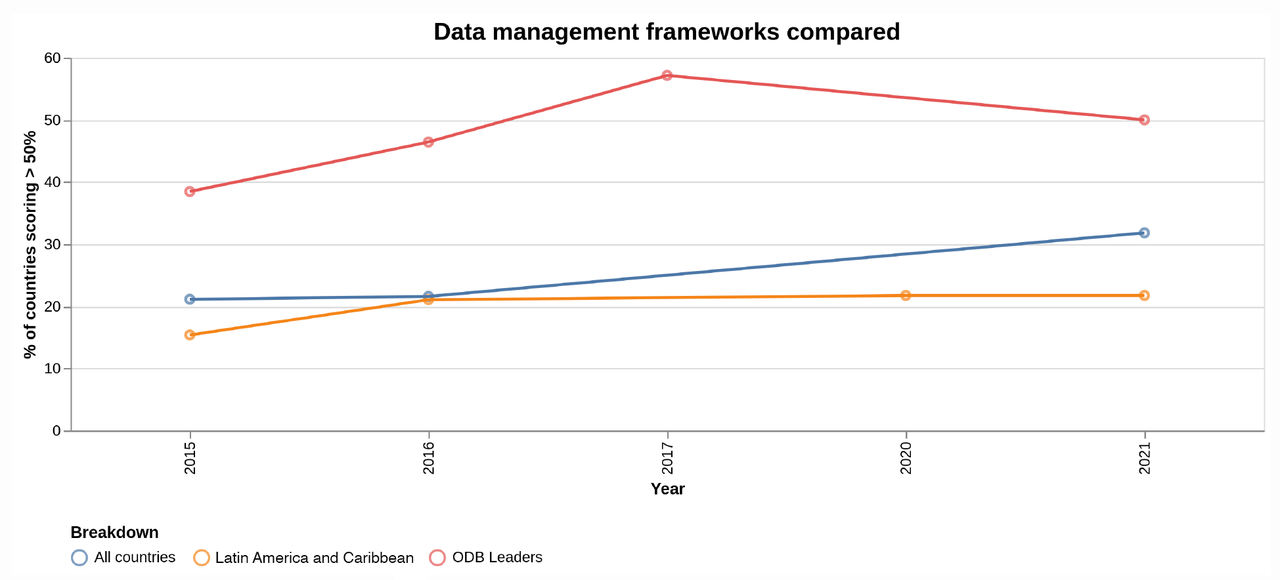

Ensuring both the quality and protection of data, while also harnessing its potential for public good initiatives, demands careful consideration in terms of data management. In this regard, juxtaposing data from the GDB, the 2015 Open Data Barometer (ODB), the 2018 ODB Leaders Edition and the 2020 Latin America and the Caribbean edition provide valuable insights. These comparisons hint at a modest global trend toward more robust data management, notably emanating from countries beyond the ODB Leaders Edition (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Comparison of Data Management Frameworks

Capacity Constraints

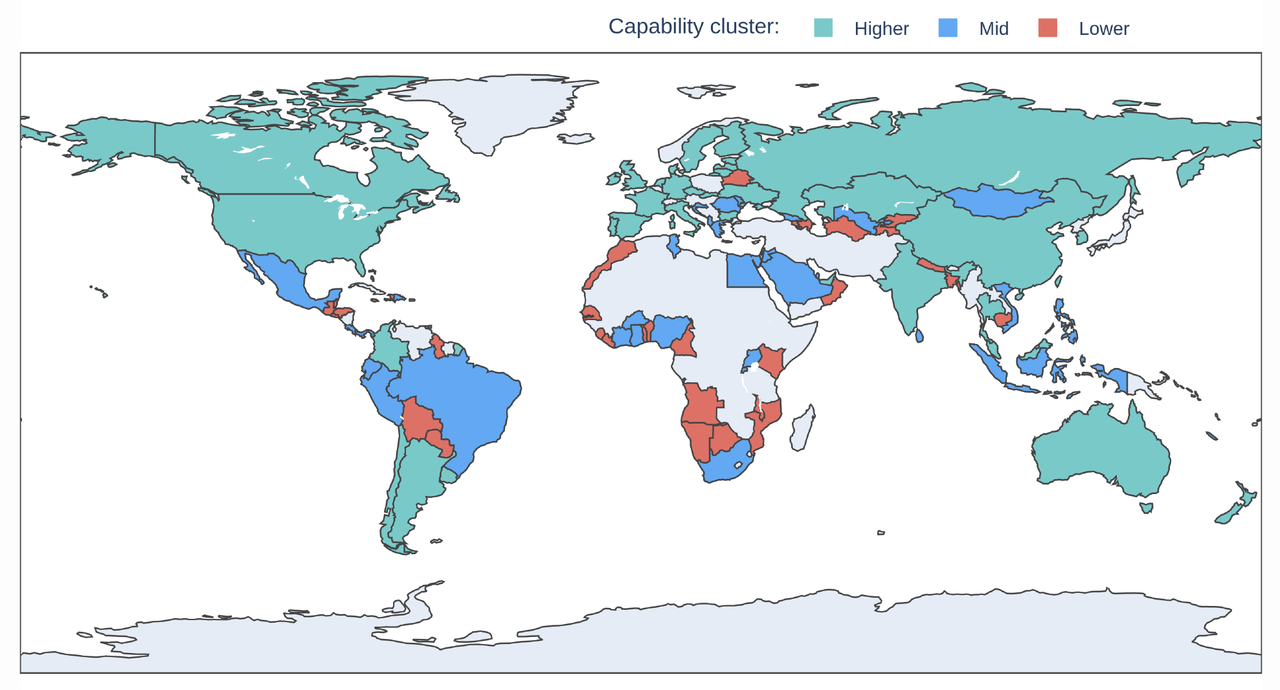

National governments play a pivotal role in data governance and stewardship, with various responsibilities including shaping data strategies, establishing and funding crucial governance bodies such as data protection authorities, offering digital services for data collection and access, and defining and adopting precise data standards. Secondary indicators within the GDB highlight the distinct hurdles encountered by countries with lower capabilities, especially concerning the presence of governing institutions responsible for data management, governance and protection. Additionally, these countries often lack essential infrastructure such as government cloud platforms and comprehensive strategies, including technology and interoperability strategies, further complicating their data management efforts.

Thus, many countries struggle with capacity constraints (see Figure 5), since they lack the resources and expertise necessary to effectively implement their data governance frameworks. This lack of skilled personnel and clear accountability mechanisms hinders their ability to establish robust data protection systems, manage data sharing effectively and leverage open data for public good initiatives. Unless these capacity constraints are addressed, the digital divide will continue to widen, and the benefits of data governance will remain out of reach for many.

Figure 5: Capability Cluster

Emerging Technologies

The rapid pace of technological advancements presents a unique challenge for data governance frameworks. New technological developments such as the advances in AI constantly raise new risks and opportunities, demanding continuous adaptation and revision of existing regulations. Data governance applies to any form of technology that collects, uses or processes data, offering a holistic and adaptable framework that can evolve with changing technologies (Verhulst and Schüür 2023). Failing to keep pace with this evolving landscape can leave data vulnerable to misuse and create unforeseen ethical dilemmas, potentially hindering responsible innovation.

Data Sharing: Trustworthy Exchange in Limbo

Access to government data has the potential to spur AI development.7 To achieve this, a multi-faceted approach that enhances data sharing is necessary. However, data-sharing, crucial for collaborative problem solving and innovation, remains hindered by underdeveloped legal frameworks.

There is still a notable absence of robust frameworks governing data-sharing practices in many countries, which could limit the accessibility of diverse data sets essential for training AI models. While 30 countries have enacted legally binding open data policies, challenges persist in ensuring standardized and interoperable data publication, which is essential for facilitating data sharing and collaboration.

This lack of robust legal structures creates an environment of uncertainty and mistrust, discouraging the exchange of information for public good initiatives. Particularly concerning is its impact on areas such as public health and environmental sustainability, where data collaboration holds immense potential for positive impact.

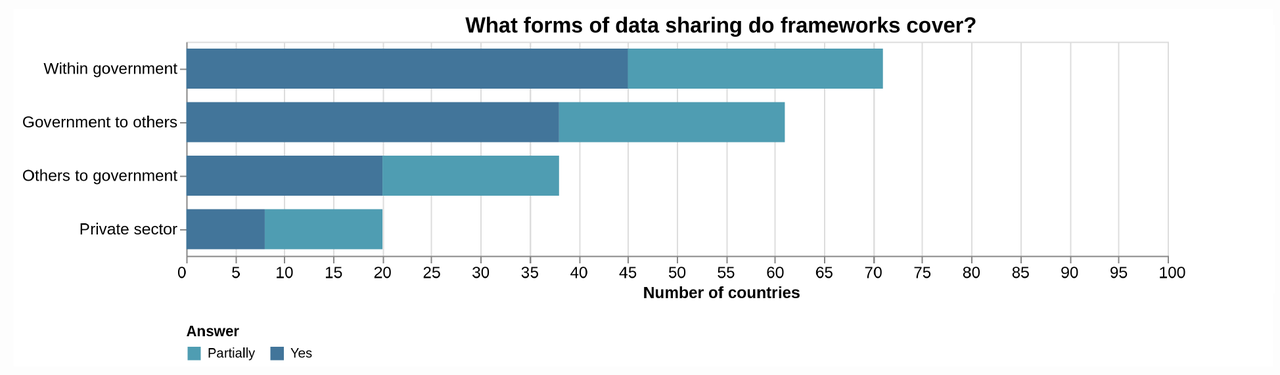

Delving into the various types of data sharing governed by existing frameworks, according to GDB data, the majority (92.6 percent of the 68 frameworks identified8) pertains to data sharing within governmental entities (GDB 2022, 27). Almost 80 percent (79.4 percent) address the sharing of data between the government and other sectors, while 51.5 percent outline protocols for data sharing from other sectors to the government (ibid.) (see Figure 6). A mere 16.2 percent explicitly cover the utilization of data in AI applications and just 26.5 percent focus on data sharing within the private sector (ibid.).

Figure 6: Forms of Data Covered by Frameworks

Looking ahead, the next decade is likely to see increased voluntary and mandated data-sharing arrangements between businesses in industry sectors, between business and government, and in support of data collaborative arrangements oriented toward addressing humanitarian and development challenges. Without clear frameworks that facilitate and govern such arrangements, there are risks that positive uses of data will be missed, and that abuses of data will proceed unchecked.

Digital Divide

While there have been notable advancements in global data governance, persistent challenges remain, particularly for lower-income countries. These nations often lack the necessary resources and expertise, exacerbating the digital gap. Balancing privacy with innovation, overcoming capacity constraints and staying abreast of emerging technologies are pivotal for fostering responsible and impactful data governance going forward.

Efforts to address these challenges are imperative to unlock the full potential of data for a more equitable and prosperous society. UN resolution A/78/L.49 recognizes the diverse levels of technological development among nations and underscores the need for cooperation to ensure inclusive access, close the digital divide and enhance digital literacy, particularly in developing countries.

There is a pressing need for investment in institutional frameworks, comprehensive data infrastructure and capacity building to harness data for public good effectively.

In that same line, the GDB highlights a widening digital divide in data governance. Lower-capability countries struggle to establish robust data protection frameworks and effective data-sharing mechanisms due to limited resources and expertise. This hampers their ability to safeguard citizen privacy and participate fully in the data revolution.

In Africa, for instance, the GDB data reveals that the region scores below the global average across all pillars (governance, capabilities, availability and use). There is a pressing need for investment in institutional frameworks, comprehensive data infrastructure and capacity building to harness data for public good effectively.

Addressing these disparities is crucial to prevent the entrenchment of existing inequalities and to ensure that the transformative potential of data is accessible to all.

Addressing the Gaps

Bridging the existing data governance gaps demands a comprehensive strategy that encompasses international collaboration, targeted support for lower-capability nations and initiatives focusing on knowledge sharing and capacity building. Empowering countries to develop robust data protection frameworks and fostering expertise in navigating complex data governance landscapes paves the way for more inclusive participation in the global data ecosystem.

Moreover, the establishment of clear and consistent legal frameworks for data sharing, including the creation of data governance bodies and the implementation of ethical guidelines, is essential for building trust and facilitating collaboration. Strengthening data security and privacy protection mechanisms further reinforces this foundation of trust.

Prioritizing standardization and interoperability is crucial to unlocking the full potential of open data, and ensuring its accessibility and usability across different platforms. Establishing common data formats and enabling seamless data exchange would empower individuals and organizations to harness the benefits of open data for public good initiatives.

Additionally, updating and reinforcing right-to-information legislation, coupled with capacity-building efforts, ensures that citizens have the necessary tools to hold governments accountable and actively participate in decision-making processes. This commitment to transparency and accountability underpins a democratic approach to data governance.

In embracing these measures, we not only pave the way for a more inclusive and equitable data landscape but also unlock the immense potential of data. By integrating the broad principles of data governance with the specific requirements of emerging technologies such as AI tools, we establish a robust framework that aligns data practices with ethical standards, legal requirements and societal expectations. This integrated approach forms the cornerstone of effective data governance, ensuring that data-driven innovation serves the collective good while upholding fundamental rights and values.