International institutional frameworks are creatures of their age — they reflect the political power relationships and technological and economic conditions of the day.

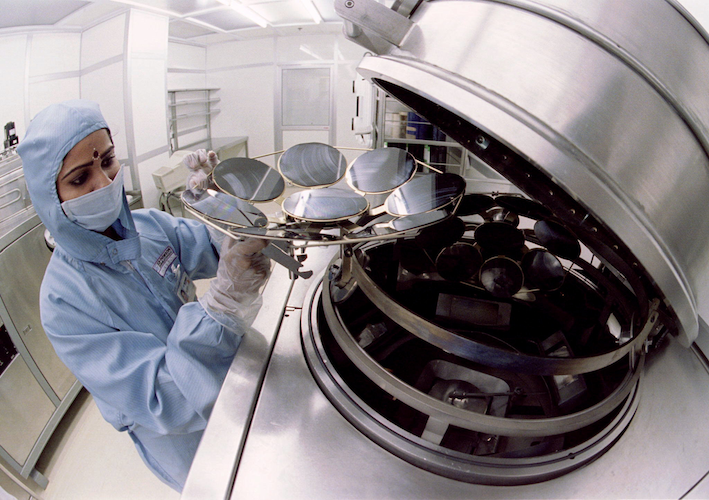

Three technological breakthroughs in the late 2000s — deep learning through stacked neural nets; the introduction of the iPhone; and the application of graphics processing units, or GPUs, to neural nets — sent the amount of data collected globally soaring while enabling the tools to exploit that data. Those breakthroughs transformed data into the “new oil” — the essential capital asset of what would eventually be recognized as the data-driven economy.

The implications for international governance were profound.

For one thing, the new technological conditions changed the terms for great-power rivalry. Whereas China entered the global knowledge-based economy some 30 years behind the United States (and remains at a distant remove, competitively speaking, in capturing international payments for intellectual property [IP]), it entered the data-driven economy more or less contemporaneously with the United States and, due to its size, with considerable advantages in terms of the amount of data it could capture.

The US-China relationship had by then changed from one of tacit alliance under the George W. Bush administration, to one of “frenemies” under the Obama administration (with its IP-focused “pivot to Asia” through entry into the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations, and the militarization of this pivot through its new “Air-Sea Battle” doctrine). When China surged into the lead in fifth-generation or 5G telecommunications networks, a critical area in the contest for dominance of the new general-purpose technologies built on the nexus of big data, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI), the relationship was further transformed. Under the administration of Donald Trump, and since then under President Joe Biden, the dynamic deteriorated to one of all-out economic war.

As for the development of economic and trade governance, the post–Second World War rules-based system for international commerce was premised on a mature industrial economy that featured, with few exceptions, highly competitive global markets in which many firms from many countries could participate (Box 1). These are ideal conditions for a rules-based system to govern trade.

Box 1: The Concept of Scale Economy

A key characteristic of industrial economies is the requirement for investment in the machinery of mass production. Because these initial investments are expensive, the average cost of production is also initially very high but falls steeply as the investment costs are spread over ever-larger quantities produced. At some point, production at the plant level reaches a stage where unit costs are minimized — in other words, the efficiency gains from producing at ever-higher scale are exhausted.

As the global economy expanded in the postwar era, economies of scale were indeed largely exhausted at the plant level, and further expansion of production was based on replicating plants. Industries that still featured above-normal profits (or "economic rents”) also attracted new entrants — new firms in new countries — which created additional competition and squeezed out excess profits. These effects were reflected in a stable share of national income flowing to labour and capital, and a stable ratio of capital to economic output — two of the famous “Kaldor facts” that characterized the industrial economy when Nicholas Kaldor wrote them down in 1961. Competitive conditions did not give rise to above-normal profits to induce strategic competition, and governments were content to allow markets to determine the allocation of production internationally.

In 1986, a generation later, as the accelerating technological change in the emerging knowledge-based economy was inducing strategic competition, Paul Krugman wrote that it was time to abandon the traditional assumption that had previously underpinned much of economic analysis: namely, that markets were not far removed from conditions of perfect competition. Indeed, Krugman’s “new trade theory” emphasized the role of economies of scale in explaining global trade patterns.

Charles Jones and Paul Romer, writing in 2010, talked about the “new Kaldor facts” that described the conditions prevailing in the (by then) mature knowledge-based economy. They emphasized that the economy was driven by ideas and human capital and thus rested on the institutional framework for monetizing ideas – the protection of IP, which generates economic rents.

In retrospect, we can now see that even as those “new facts” were being written down, yet another new set of facts was emerging, those that would characterize the data-driven economy.

With 20-20 hindsight, we can see that the conditions that supported the emergence of a rules-based system in the industrial era represented a transient state. In the early 1980s, technological change enabled an acceleration of the pace of innovation by industrializing research and development. The key developments were the introduction of the IBM personal computer in 1981 and the release of computer-aided design software for it in 1982, which gave affordable access to CAD/CAM (computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing) techniques to smaller companies, start-ups and entrepreneurs working across the waterfront of industry. The transition to the knowledge-based economy was under way, graphically captured by the “hockey stick” upturn in the pace of patenting in the United States, the leading-edge country.

With 20-20 hindsight, we can see that the conditions that supported the emergence of a rules-based system in the industrial era represented a transient state.

The key productive asset of the knowledge-based economy is IP, the monetization of which depends on the protection that laws against infringement provide. The above-normal profits or “economic rents” that this protection enables compensate for the upfront investment in research and development at the IP production stage, and the advertising at the marketing stage, where the protection of brands comes into play. Again, with 20-20 hindsight, we can see that the shift into this world of protected returns to capital coincided with the beginning of a long trend rise in the capital share of national income, the erosion of the labour share of national income, and the rise of incentives for strategic behaviour to capture these rents. The World Trade Organization (WTO) was designed for the win-win world of trade, not for the win-lose world of economic rent-seeking. Not surprisingly, its system of governance started to break down, and trade negotiation action shifted into regional trade agreements where the larger, more powerful economies could press their advantage.

These considerations apply even more strongly to the data-driven economy, which is even less well suited for a rules-based system than was its predecessor. The data-driven economy features powerful economies of scale, economies of scope, network externalities in many sectors, and pervasive information asymmetry (information asymmetry is, in fact, its business model). All of these individually lead to market failure; combined, they result in the creation of large, valuable economic rents that become a bone of contention and that confound policy instincts honed on the experience from an earlier era of limited rents.

The transition in the nature of the economy was reflected in numerous ways — the era was described in terms of superstar firms, of rising market concentration, of proliferating unicorns (billion-dollar private start-ups preparing to go public), of a steeply rising share of intangibles in the market capitalization of companies, of a new gilded age, of technology CEOs behaving like Renaissance-era princes, and so forth. The wealth that defined this era consisted of economic rents.

In addition, the digital transformation, with the move of social and political interaction, alongside commercial activity, to online platforms, creates fundamentally new sets of problems in terms of preserving national sovereignty (safeguarding of democratic processes from data-driven manipulation on social media), safeguarding national security, and preserving boundaries between the private and the social. The WTO system was designed for a world of trade in “inert” products moving across controlled borders, not for the borderless world of platform firms and products that continuously stream data into the cloud. The weaponization of data for information warfare was not long in coming; the recognition of the qualitatively new national security risks to the backbone infrastructure of the economy (transportation, telecommunications, energy and finance) could hardly be missed, particularly with the Internet of Things revolution under way.

The regulation of the collection and use of data poses complex and vexing challenges in and of itself. However, addressing these issues is not enough. The regulation of the data-driven economy and the development of institutions to mediate the tensions inherent in the changed geopolitical context enabled by the new technological conditions are additional to these issues and indeed compound the problems of developing effective and desirable guardrails for data. We need to regulate data, but we also need to work out how to regulate the data-driven economy and find new international governance protocols — formal or tacit — to stop the slide into ruinous conflict. The mercantilist contest over the economic rents generated by the first industrial revolution expressed itself in the competition to dominate foreign markets — the “Scramble for Africa”; the Opium Wars, to literally open the Chinese market to Western goods, including opium; the establishment of “banana republics.” When the world ran out of room before it ran out of economic rent potential, the industrial powers turned on themselves in the industrialized carnage of the twentieth-century world wars. In the age of data, we are already engaged in the Third World War, in economic terms.

Specific Challenges

The transformative changes outlined above create the challenges. How have we done with creating solutions for the regulation of the data-driven economy?

- Addressing trade in data: Regimes have been developed to facilitate e-commerce, but no regime has been developed to address the implicit trade in data, or the sharing of the benefits of the data-driven economy. In particular, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development/Group of Twenty (OECD/G20) Inclusive Framework, which was developed as a response to concerns about multinational corporations operating in countries where they had no taxable local establishment, addressed the issue of virtual presence of multinationals by allocating profit taxation rights to end-use markets, but it did not address the issue of the value of data. Data drives the modern economy but is not in the national economic accounts or the trade statistics. It shows up, imperfectly, in the market capitalization of corporations.

- Dealing with trade in digital products: The WTO still talks about “electronic transmissions,” without drawing necessary distinctions between “durable” and “non-durable” intangible products (analogues to goods and services, respectively), and with the flow of technology across borders (for example, technical instructions for 3D printing).

- Addressing national security concerns: The changed circumstances of the data-driven economy are implicitly captured by the dropping of the original illustrative examples of developments that would trigger the national security exception in the WTO Agreements, but no new language has been developed to circumscribe the use of these exceptions to limit trade or investment in the modern context.

- Addressing national sovereignty considerations: In a world that has been literally turned upside down by information/disinformation wars (bot-driven political influence campaigns that delivered Brexit, Trump and populist campaigns, and are now driving the contest to influence international policy in the Russian invasion of Ukraine), the answers are not apparent — state-led censorship is as problematic as private sector filters on social media.

- Preserving boundaries between the private and the social: A workable regime to limit corporate or state surveillance has not been developed. This battle is being waged at the municipality and social activism level (for example, over the use of facial recognition systems in public spaces).

- Governing rights in intangibles: Trade secrets legislation has been revised to reflect the importance of this type of IP protection for data and algorithms, but the manifold issues raised by the industrialization of research and development that drove the knowledge-based economy, and the industrialization of learning that drove the data-driven economy, have not been addressed. We retain IP regimes designed for the Renaissance in a world where product life cycles have shrunk to two to three years and the written word and images have proliferated in literally astronomical amounts.

- Reforming competition regulation: Conditions of the data-driven economy ensure market failure. There has been much discussion of the regulation of platform firms but so far no consensus on how to deal with their impact on conditions of competition.

The still bigger challenge is that the era of the data-driven economy is probably mostly behind us. While it started about 2010, and significant relevant policies were adopted by mid-decade (by 2016, for example, we had witnessed the inclusion of data provisions in free trade agreements and the revision of trade secrets laws), it was widely recognized in the academic literature as a new type of economy only about 2016 and by the political system even later — Shinzo Abe referred to the data-driven economy in a 2019 speech at Davos, noting that “we have yet to catch up with the new reality, in which data drives everything.”

Since then, truly fundamental technological breakthroughs in scaling AI technology have been made that will usher in a new economic era:

- Specialized AI computer chips broke through the trillion-transistor mark; by 2022, the largest transistor density was 2.6 trillion.

- AI systems grew from a scale of 100 billion AI parameters to a trillion parameters, then to 10 trillion, and could reach 174 trillion — “comparable to the number of synapses (1000 trillion in the human brain)” — in a few years.

- Power requirements to run AI chips are being reduced dramatically through innovation in design.

- Meanwhile, the power of AI systems is being increased by orders of magnitude. For example, Amazon claims its 20 billion parameter Alexa Teacher Model, announced in August 2022, has matched the benchmark performance of systems with hundreds of billions of parameters. Similarly, in January 2022, Microsoft announced its DeepSpeed system promises to reduce training costs by a factor of five.

Training times are plunging. Specialized AI systems are now routinely breaking through human benchmarks. AI systems have now been awarded patents. AI-piloted fighter jets have out-duelled human-piloted jets in dogfights. The Beijing Winter Olympics showcased a suite of service robots deployed to address pandemic-related concerns.

Truly fundamental technological breakthroughs in scaling AI technology have been made that will usher in a new economic era.

We are just at the beginning of this new era. AI research is being conducted on a similarly massive scale. Baidu reports that its deep-learning platform, PaddlePaddle, is being used by 4.77 million developers in 180,000 companies in China and worldwide. Tens of thousands of companies in the United States are using Google’s TensorFlow system, Microsoft’s PyTorch and other platforms. Notably, the Baidu system is optimized for industrial users, whereas the US systems are more demanding in terms of deep-learning understanding — in other words, we are seeing international specialization in advancing the state of the art.

If we think about AI from a technical perspective, what is top of mind is the suite of problems — brittleness, bias, catastrophic forgetting and so forth, especially in higher-level applications. From a governance perspective, we see a plethora of challenges related to ethics, standards and unseen consequences. From an economic perspective, as discussed here, we see a looming Cambrian explosion of applications, mostly low-level and narrow at the beginning but becoming increasingly powerful as AIs combine and recombine to form ever more powerful applications, cumulatively working to disrupt, from the bottom up.

Just as the industrial revolution transformed the production of goods, our human-capital-intensive services industries are about to be transformed by the widespread deployment of machine knowledge capital, which will compete with human knowledge capital much as the machinery of mass production competed with human labour, and will intensify the competition with labour by making production machinery more flexible and much, much smarter.

Importantly, machine knowledge capital will make services sectors scalable, lifting the constraints imposed by the so-called Baumol effect, which described the tendency for economic growth to slow down with the transition from industrial to post-industrial services-intensive structures, with incalculable impacts on economies and societies organized professionally and socially around the returns to human capital.

Required International Institutional Reforms

Today, we are talking about catching up with the institutional requirements for addressing the data-driven economy; we also need to be thinking about its continuous transformation into the machine knowledge capital era. The scale and complexity of the implied responses are staggering:

- New international “clubs” to mediate the tensions in the new multipolar world and provide for collective security for the smaller powers as geoeconomic rivalry spills over into kinetic war.

- A WTO 2.0 that preserves as much of the rules-based system as possible for the mature industrial economy that still operates in modes suited for rules, while developing a regime for digital trade. This process includes a review of existing WTO commitments made prior to the digital transformation that may no longer be tenable, given all that the digital transformation entails for national sovereignty, security and privacy.

- An international agreement on sharing the asset value benefits of cross-border data flows that complements the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework.

- Fundamental reforms to IP regimes to reflect the shift of innovation into machine knowledge space.

- New social contracts to deal with the impact of machine knowledge capital on societies ordered by the returns to human capital.

These are meta reforms that acknowledge and integrate the numerous micro reforms needed to regulate data and its derivatives — namely, machine knowledge capital based on scalable AI applications.

The rapidity of technological change makes these reforms all the more difficult because the asymmetry across economies grows as the leading edge pulls away from the pack and the diffusion of technology lags. One can only guess at the power of the centripetal forces that will concentrate the energy of this economy in, at most, a handful of centres, and what that will mean for the periphery (which may include most of the population in the leading-edge economies) — particularly when the risk of falling behind is perceived as existential because dual-use technologies are at issue and precautionary principles are then thrown to the wind.

Finally, how do we manage change when lived experience is inadequate to guide reforms as technology is adopted without referendum? No one said it would be easy.