A fatalism has infected the deepening Sino-US divide, an echo of the jockeying between America and Japan in the Pacific leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor — one that says war is inevitable. Chinese President Xi Jinping has gathered all state authority for himself; he is 70; he is determined to seize Taiwan in his lifetime. The United States won’t permit its global reach to be thus circumscribed, and rightly so.

So sooner or later, goes this thinking, the two superpowers will fight. Commerce, sometimes posited as a kind of geopolitical superglue that dissuades people of different countries from trying to kill each other, has its limitations. It’s ever-more clear that the effort to seize, occupy and control Ukraine has been an economic, political and strategic disaster for Russia, though that war drags on. So much for reasoned self-interest in the affairs of great powers.

Yet by the same logic, war isn’t inevitable, either. It’s contingent on decisions made by individuals. The best modern example is the Cold War, which ended without ever going “hot” — despite the two sides, armed with doomsday weapons, bristling and snarling at one another across Europe for 45 years. How did the worst outcome not happen, in that case? And how can this inform the West’s engagement with China, now?

The march to the fall of the Berlin Wall famously began when President Ronald Reagan and Communist Party of the Soviet Union General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev met in Reykjavík, Iceland, over two days in October 1986. As the legend goes, the two men sat across a table, looked each other in the eye, and had a simultaneous “Eureka!” moment where each suddenly understood the other’s sincere desire for peace.

Although those meetings ended without resolution, they set the stage for real progress in 1987, via the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Reagan and Gorbachev at that point had become locked in a virtuous cycle of one-upmanship. Reagan’s advisers white-knuckled it through those meetings as they grasped the extent of the astonishing commitments being made, which they were convinced were impossible. But a personal bond of trust had been forged, which became the foundation of the historic peacemaking that followed.

Gorbachev, judging from his own accounts, came to Reykjavík desperate to step back from an arms race he believed the Soviet Union had lost.

It’s a nice story. There’s probably even some truth to it. But like most sepia-toned retrospectives on the Reagan era, it brushes out some facts. The first is that Reagan believed in, and insisted on upholding, even at Reykjavík, the promise of his Strategic Defense Initiative, the “Star Wars” program, which he mistakenly thought could provide an impregnable defence against Soviet missiles. The second is that the United States had achieved, by the mid-1980s, vastly superior capabilities in conventional weapons, because Reagan had been preparing for war since 1981.

Third, and most important, Gorbachev, judging from his own accounts, came to Reykjavík desperate to step back from an arms race he believed the Soviet Union had lost. As he wrote on the twentieth anniversary of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the accident was his personal pivot point: “The nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl this month 20 years ago, even more than my launch of perestroika, was perhaps the real cause of the collapse of the Soviet Union five years later.”

The most relevant and true part of the myth is this: When Gorbachev extended his hand, Reagan took it. An America ratcheted into a militaristic frenzy by years of triumphalist, post-Vietnam propaganda, girded for a war that might have ended civilization, instead allowed itself, and the rest of us, peace.

The lessons with respect to China today are twofold.

First, deterrence works. “If you want peace,” the Roman general Vegetius wrote in the fourth century, “prepare for war.” The North Atlantic Treaty Organization standard for defence spending, two percent of GDP, is a peacetime benchmark, but we are no longer living in a peacetime world. Countries that chronically undershoot even this mark, as Canada has done under both the major federal parties since the early 1990s, are shortchanging the cause of peace.

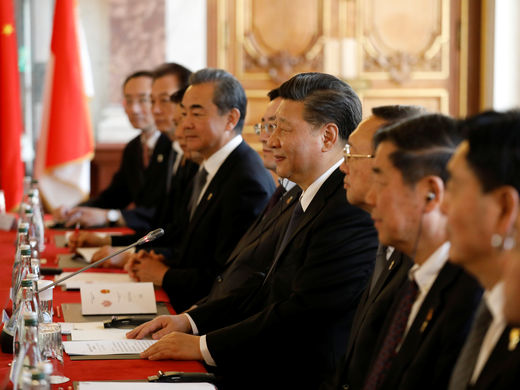

Second, even as the Sino-American gulf widens, it’s more important than ever to keep diplomatic channels warm. Bodies such as the Group of Twenty, or the United Nations itself — flawed though they may be — are the ones we have. They must be upheld, supported, championed — even as the pressures for their sidelining by the great powers grow.

Among other effects, Russia’s attack on Ukraine has brought into sharper relief the chasm of aspiration between China and the West. It has also proven, again, that nations don’t always act wisely, or even in the narrow best interests of their leaders. Because nations are led by individual humans, who are flawed, nations make mistakes. Their biggest mistakes — the 2003 US invasion of Iraq comes to mind — are catastrophic.

But if history tells us anything, it’s that the worst outcomes can be averted, and often have been. That is a vein of optimism worth remembering, in 2023.

This article first appeared in The Globe and Mail.