On June 18, 2020, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that Canada would join the ranks of governments launching a mobile contact-tracing application as part of the national response to COVID-19. That announcement came a few days after Norway’s government shut down its app for failing a necessity and proportionality analysis, the United Kingdom abandoned its contact-tracing app project in favour of the Google-Apple model and reports that Australia’s app was working on just 25 percent of phones. In other words, there was a lot of attention paid to contact-tracing apps at all political levels, despite their questionable — if not actively harmful — role in the response to COVID-19.

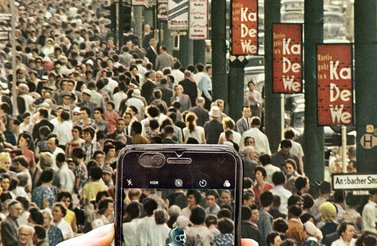

Whether it’s the national release of contact-tracing apps meant to battle a pandemic, or Sidewalk Labs’ (now defunct) bid to create a “city built from the internet up,” public conversations about major policy initiatives tend to focus on technological components and evade significantly harder questions about power and equity. Our focus on the details of individual technologies — how the app will work, whether the data architecture is centralized, or the relative effectiveness of Bluetooth — and individual experts during the rollout of major policies not only is politically problematic, but also can weaken support for, and adherence to, institutions when their legitimacy is most critical.

There was a lot of attention paid to contact-tracing apps at all political levels, despite their questionable — if not actively harmful — role in the response to COVID-19.

There’s a well-documented history of the tendency to hype distracting, potentially problematic technology during disaster response, so it’s concerning, if not surprising, to see governments turning again to new technologies as a policy response to crisis. Expert public debates about the nuances of technologies, for example, provide serious political cover; they are a form of theatre — “technology theatre.” The term builds on security expert Bruce Schneier’s “security theatre,” which refers to security measures that make people feel secure, without doing anything to protect their security. The most prominent examples of security theatre are processes such as pat-downs at sporting events or liquid bans at security checkpoints in airports. Technology theatre, here, refers to the use of technology interventions that make people feel as if a government — and, more often, a specific group of political leaders — is solving a problem, without it doing anything to actually solve that problem.

Contact-tracing apps are the breakout technology theatre hit of the COVID-19 response. Governments all over the world have seized the opportunity and are using an array of powers to launch almost entirely ineffective and often outright dangerous technologies. More alarming, there has been very little push to meaningfully prevent those deployments, challenge government arguments around necessity and proportionality, or question the decisions to resource these technologies, many of which were not cheap to develop or deploy. Instead of focusing on the underlying power issues, most public institutions and experts have focused on the nuances of the technology.

Technology theatre is particularly visible when expert debate, amplified through broadcast and digital platforms, creates the appearance of public debate while doing very little to meaningfully engage the public. When the public is focusing on a technology instead of a holistic solution to address complex policy issues, technology theatre is working.

The largest and most damaging cost of technology theatre is the political fragility that results when institutions are built without public understanding, investment or interest. Substituting expert input for public support is a structural choice, with major impacts on the amount of public debate or engagement that precedes large project announcements; the accountability of the people involved in designing and defining institutional change; and the standards and protections available to the public to challenge decisions. Each of these shifts structurally changes the way that activists or members of the public are able to raise concerns, define new protections or engage, which functionally limits the scope, focus and long-term value of institutional growth initiatives, by undermining their legitimacy. Whether technology theatre is deployed as a political tactic, or is simply a growing pain associated with a burgeoning technology industry, it is a real threat to the integrity of the industry and, more importantly, the entire world of industries that have focused on digital transformation as the next leap in their institutional growth.

Most industries use some form of specialist expertise, which is then held accountable through public engagement; in public services, usually that’s measured by impact, and in technology, it’s usually measured by adoption. Even that small difference can create a cumulative cost — and technology companies’ complicated relationship with their impacts on the public and trust was reaching critical cost levels before the pandemic. That’s not to argue for one or the other, but rather for a clearer logic and process for managing the balance between expertise and public engagement. There has been significant debate about governments’ progressive turn toward privatization, managerialism and austerity, much of which was designed by well-insulated experts inside of academia and policy institutions. The problem with expertise is that it’s politically fragile — expertise can lead in defining potential solutions, but democracy is designed to require public support for large changes and long-term sustainability. In most democracies, this power is managed through budgetary authority, which, especially in countries focusing on privatization and digital transformation, has shifted toward executive agencies and procurement processes. And, public institutions are starting to experience the political fragility of relying on expertise.

The World Health Organization (WHO), for example, is an obviously important international institution during a pandemic. Yet, less than a month ago, President Donald Trump announced that he would end the United States’ WHO membership and funding (while theatrically alleging that the organization demonstrated political bias in favour of China in the sharing and reporting of COVID-19 information). While this is the latest collateral damage in President Trump’s political standoff with China — the United States is the WHO’s largest funder and, historically, one of the champions of global public health — it’s worth recognizing that there has been very little domestic pushback on Trump’s decision to withdraw from the WHO. The problem isn’t that the organization isn’t valuable, but that the public doesn’t understand what it does or why it’s valuable. This lack of awareness can be attributed, in part, to technology theatre. Rather than acting as a patient voice of scientific authority, the WHO is focusing on unproven technology initiatives and backtracking on important guidance. For example, in the aftermath of high-profile guidance reversals on the utility of face masks and the prevalence of asymptomatic transmission, a range of public health experts raised questions about the WHO’s legitimacy and role. Those questions in turn, impact public trust in the institution, public willingness to push back on Trump’s decision, and ultimately WHO’s bank account; it is about to lose its biggest donor in the middle of a pandemic.

When the public is focusing on a technology instead of a holistic solution to address complex policy issues, technology theatre is working.

The political fragility of expertise isn’t new — but in the context of technology theatre, it’s creating an under-examined layer of fragility in public digital transformation projects, the governance of which is handled very differently than most might assume. We tend to think governance happens by way of representative, legislative debate, flawed as it often is. With these projects, that’s not always the case, which creates two significant, structural problems.

First, the digitization of public institutions changes the balance of government power, by shifting a number of political issues out of public process and framing them instead as procurement processes. Whereas questions around executive authority were historically defined in legislation, they’re often now defined in platform design — and disputes are raised through customer service. This shift extends executive power and substitutes expert review for public buy-in and legitimacy, in ways that cumulatively result in a public that doesn’t understand or trust what the government does. Importantly, the transition from representative debate to procurement processes significantly changes the structures of engagement for public advocates and non-commercial interests.

The second structural problem results when nuanced conversations about the technical instrumentation of a publicly important governance issue are sensationalized. For example, focusing on COVID-19 contact-tracing apps instead of the large institutional efforts needed to contain infection frames the issues around the technology and not the equities or accountability required to serve public interest mandates. One of the reasons for this is that experts, like everyone else, are funded by someone — and tend to work within their own political, professional and economic perspectives, many of which don’t take responsibility for the moral or justice implications of their participation. Consultants tend to focus on technical solutions instead of political ones, and rarely challenge established limits in the way that the public does.

Said differently, technologies are a way to embed the problem of the political fragility of expertise into, well, nearly everything that we involve technology in. And public institutions’ failure to grapple with the resulting legitimacy issues is destabilizing important parts of our international infrastructure when we need it most.

Whether we’re talking about Sidewalk Labs’ approach to digital governance, the mostly disproven value of COVID-19 contact-tracing or notification apps, or whatever comes next, there are real, knowable impacts, challenges and second-order effects of expecting technology to mediate the relationship between institutions and the people they serve. No matter the challenge, there are technology companies, academics and non-profits agitating for the use of increasingly surveillant technologies to monitor, model and predict complex social problems — often without considering whether deploying such tools would aggravate the people or trust relationships involved. There is no app architecture to prevent police abuse, no amount of computational surveillance to arrest climate change and no group of expert consultants who can replace the value of clear, equitable public legitimacy. Ultimately, apps, much like the government policies designed to regulate technologies, are instruments designed to reflect and support the will of the public. They do not change the public’s mind, compel adherence or conjure effective systems by themselves.

Technology theatre, like all theatre, can be a powerful demonstration, but more often it is merely a distraction. And it is the sign of an immature industry — you rarely see such public display around the technical nuances in more mature fields, such as medicine or engineering (of course, that doesn’t mean they’re free of their own politics and theatre). But more than that, and more concerning, technology theatre is short-term political thinking that has resulted in a number of high-profile digital governance failures — most recently, the United Kingdom’s and Australia’s attempted contact-tracing applications. The true test for any public program, digital or otherwise, is whether it’s demonstrably useful enough to the public or vital enough to the institution or, ideally, both, that the program achieves broad political support and sustained investment.

When public institutions substitute expert consultation for public input and control, they only build half of the necessary constituency for sustainability and legitimacy. And, because that expertise is often procured, the outputs tend to over-index government convenience and risk management — leaving public equity and any likely second-order impacts as afterthoughts, if they are thought of at all.

Public Participation Going Dark

The transition of the conversation about how public institutions should evolve, from legislatures to procurement processes, has a range of effects on people’s basic rights and fundamental freedoms. In many ways, the modern evolution of public institutions is difficult to meaningfully separate from digital transformation — and technologies increasingly act as the front line for not only the services that governments provide, but also the ways in which they surveil their public. Digital transformation is a significant part of the evolution of governance powers — the kinds of powers meant to be defined and checked by other public institutions or, failing that, the public.

The problem is, technology is a largely unregulated industry, and very few legislatures have proven their ability to meaningfully change technology companies’ behaviour. Nevertheless, there are significant pressures from both industry and politics to improve efficiency and to modernize — which means that governments continue to procure and use technology in the way they serve people. Governments are procuring services from an industry they largely know they can’t control, and intermediating them in their most fundamental operations.

The problems posed by using technology and private contracting processes to administer public institutions and services have been extensively studied and are beyond the scope of this piece. Here, let’s consider three structural shifts that are shaping this change.

From a Legislature to a Contracting Officer

Procurement is structurally different to legislation. Most legislative processes create a forum for debate, a structure for iterative negotiation and a way to hold negotiators accountable to the public’s interest (as opposed to a professional ethics standard). Procurement, by contrast, typically starts with an organization issuing a request for proposals (RFP), which singularly frames a need, which is then responded to individually by a group of vendors and, finally, approved and implemented by the issuing agency. If that sounds dry, it is! And that’s part of the problem: procurement is designed to be limited, transparent and instrumental, whereas legislation is inherently messy and slow but a legitimate way to grapple with complex social issues. Where public governance is judged by whether it solves a problem for all the people it serves, public procurement is judged according to the professional standards of contracting.

Governments are procuring services from an industry they largely know they can’t control, and intermediating them in their most fundamental operations.

For activists, that means that challenging procurements has to focus on either challenging the authority of the issuing institution to issue the RFP; arguing that the RFP will result in an imminent and knowable harm; or arguing that the outcome of the process is in some way invalid. Each of those challenges is legally and procedurally difficult (and expensive) to make — and all require the kind of vigilance that is absurd to require of the public. As a result, a significant number of procurement (and regulatory) processes are dominated not by people focusing on directly representing the public’s interests, but by professionals with the resources and reasons to invest. There is a profound difference between being able to debate and constructively decide how to solve a problem, as legislatures are designed to do, and having to challenge the integrity of a civil servant or their institution to raise predictable policy challenges posed by digital transformation projects. There are, in various stages of maturity, a number of technology-focused auditing campaigns that try to address this gap, but they struggle to realistically predict the full range of potential harms based on a scaled deployment of emerging technologies.

From Legal and Electoral Accountability to Procedural and Professional Responsibility

The shift to procurement also means that when the public wants to challenge, change or improve a technology-intermediated public practice, the tools available to them are very different. In most democracies, executive agencies are designed to work with legislative oversight but limited direct accountability to the public. As a result, fundamental choices — including choices related to partner companies, appropriate standards, users’ abilities to challenge the impact of technologies and folks who aren’t likely to use a technology — are made by mostly well-meaning civil servants, not the people who most represent the public. The implications of that shift in accountability and incentives are profound.

In many democracies, there are a number of public and institutional records of the ways that representatives vote, participate in governance and serve constituents. And, of course, there are elections, which, however problematically, establish regular intervals and avenues for accountability based on the substance of the elected’s work. Holding civil servants accountable is mostly done through their employment and professional ethics; there are rarely accountability mechanisms that focus on transparent disclosure of the performance of individual civil servants, nor is it easy to challenge the authority of executive agencies, RFP by RFP.

That’s by design, and normally a good thing — the goal is not so much to hold individuals accountable as to ensure that the instrumental interventions that procurement is designed for are supported by policies that reflect public debate, instead of privately contracted platforms. Here, the cultural alignment problems are often more damaging than direct accountability; legislative representatives typically develop significant infrastructure to communicate about their work with their constituents, whereas executive agencies are more focused on protecting the institutions’ interests. While those things should align, they can get distorted by technocratic and market influences, which public participation is meant to correct. When executive agencies move to procure technology solutions and interventions as elements of their core services without having any of the necessary accompanying policy and participation frameworks and infrastructure in place, the effect is often limited public adoption, understanding or ability to help improve the service.

From Government Action to Due Diligence plus Functional Review

In the same way that shifting institutional evolution initiatives from legislation into procurement changes the process and the people, it also changes how we evaluate the output. Most democracies hold governments to a higher standard than the private sector, so when the government privatizes something that it historically did, it generally lowers the standards, and often the accountability, that the public can use to judge or shape that service. Human rights protections, for example, typically apply to direct government action, and only apply in limited circumstances to private companies. For example, if you can prove that a government policy or service is biased against you, you can challenge and change that service. By contrast, it’s much harder to get the information to know whether a government service that’s delivered through a privately administered technology is biased. And, as described in Ruha Benjamin’s Race After Technology and Virginia Eubanks’s Automating Inequality, even when a technology’s bias is proven, it can take significant political pressure to make any changes. There are important anecdotal victories — for instance, the commitment of several major American technology companies to temporarily suspend selling facial recognition technologies to police — but they come after years of dedicated campaigning from brilliant scholars (here, Deborah Raji and Joy Buolamwini) and an explosive political moment, which, most would agree, shouldn’t be required for the public to be able to shape public institutions’ digital transformation.

The systemic tools that we do have for public engagement in procurements are typically based on the contractual process, rather than about the substance of the project, which can make this engagement significantly more difficult than engaging with legislation. Whereas you can call your representative to show constituent support for particular issues, you can usually only challenge the frame of an RFP through a discrete, controlled question-and-answer process. If you participate in the process itself, you can challenge the validity of the final decision, but you typically have to do so by proving that the contracting office acted inappropriately, not that the proposed project has untenable or unsolvable implications for the rights of the public. Perhaps more concerning, whereas legislative processes are built to create new protections for constituent interests, procurement generally only applies existing protections — even if the project has implications for people’s fundamental rights. That means that procurement challenges have to resort to the public protections of the present (at best) and, more commonly, the past to prevent the harms of the future.

At a fundamental level, the transition of many important institutional processes into procurement limits the public debate infrastructure, accountability and standards that we use to protect the public. Those limitations are most felt during disasters, when governments are pressed to act. As the stakes around the COVID-19 response continue to rise, so do the instances of technology theatre, deployed to distract us from floundering governments. And, while we have been focusing here on the government’s responsibility for technology theatre, there couldn’t be any company or show without a willing troupe of actors.

COVID-19 Needs More than Bread and Circus

The global response to COVID-19 has included no small amount of technology theatre, convened by governments, but dutifully acted by a cast of academics, policy professionals, technology companies and opportunists. There have been billions of pixels spilled over the potential of data, artificial intelligence and any number of surveillance technologies to be the thing to manage co-existence with COVID-19. Meanwhile, public health professionals warn that vaccines are a long way off and that these vanguard technologies are doing very little to help in the response. If anything, as evident in places like the United Kingdom, Australia and Israel, government technology incompetence and surveillance can actually undermine the public’s faith in the broader response. Rather than retrench by focusing on known public needs, most governments are doubling down, dogged in the need to release some form of public contact-tracing app. And the digital policy community — the professionals who advocate, legislate or study the impacts of technologies — mostly took their places in the bright lights.

The first act of the contact-tracing app has already included a range of performances, like the splashy protocol partnership between Google and Apple, which has been rolled out through operating system updates to phones all over the world, without any public input. Or the earnest — if myopic — European debate about the relative centralization of data architecture between academics and policy makers. There is a huge number of conflicting expert analyses of the comparative efficacy of Bluetooth protocols and geolocation, and a number of institutions are developing wearable tracking devices, despite public rebuke. Even more troubling, a range of spyware and malware tools are being deployed under the cover of contact-tracing apps — even, reportedly, by governments. And, of course, there is the usual amount of commercial abuse, such as data brokers’ reselling of citizens’ health data on the open market. All of this debate, on the intricacies of technology design and the systemic patterns of abuse that come from largely unregulated markets, misses the forest for the trees. Once we start focusing on the technology, we can start to forget that it doesn’t work, is highly experimental and is exceptionally prone to abuse through bad governance.

Drawing you in is, after all, what good theatre does.

The truth is that launching and, in many cases, compelling the use of a technology — even during an emergency — is a step change in governmental power. In most democracies, significant changes to government power, especially during emergencies, are subject to substantial review and oversight by other parts of the government. In the short term, these checks have done little to slow contact-tracing technology development or deployment, exposing just how little science, public health or efficacy seem to have to do with pressures to expand surveillance powers. Almost all of the meaningful decision making about COVID-19 technologies has been done behind closed doors, outside of government and by people with a vested interest. This dynamic isn’t particularly unique to technology, but the rise of the digital policy space as an expert realm — rather than one where we, the public, engage politically — has significant costs to our literal and figurative health.

Casting the COVID-19 Debate

The world doesn’t know how to regulate the technology industry. That’s not to say it can’t, but no one has done a particularly convincing job to date. New communication technologies often have significant impacts on politics and, in particular, on administrative authorities. Unlike traditional industries, governments rarely control digital markets, and most of the ways that government regulates business (access to markets, access to infrastructure/labour, taxation and so forth) don’t translate cleanly to the scale of service that internet or digital platforms provide. The number and size of issues that technology creates should be a call to action for a generation of public servants. Instead, most governments have turned to the experts.

Technology expertise can take many forms, but usually it is exerted to make decisions about how a technology should be designed — and typically without meaningful public input or accountability. The problem is that the most dangerous things that happen through technology are more about the absence of meaningful public input and accountability than they are about the technology itself. There are lots of so-called private and secure applications that can’t prevent employment discrimination, de-escalate political violence or improve otherwise overwhelmed public health systems. So, when major policy and governance issues arise, it is often more convenient to focus on the design of a technology than how a technology will actually solve public participation and accountability challenges, or stop a pandemic, for that matter. While it’s hard to describe or label the group of people who work to influence the way that technologies influence our basic rights, for the purposes of this piece let’s call them “the digital policy community.”

Once we start focusing on the technology, we can start to forget that it doesn’t work, is highly experimental and is exceptionally prone to abuse through bad governance.

Members of the digital policy community, unlike public representatives or legislators, do not necessarily have a direct mandate, nor the inherent protections direct mandates are meant to create. There is no public interest support for digital rights advocates, so they are forced to rely on patrons for funding and access to influence. Strong structural barriers — perhaps created by the acceptance of funding, or due to the limitations of those the advocates seek to influence — impede this community from proposing political ideas, let alone radical reforms. And when public rights advocacy is contingent on the patronage, amplification or consideration of well-positioned, private interests, there are real, cumulative costs to the legitimacy of the whole community of practice. Experts in these institutions are neither able to fall back on the credibility of representation nor to claim independence from the politics required to be heard. The community is thus left vulnerable and dangerously out of sync with the people who experience the failures of technology and politics most directly.

And it is here, of course, where expertise becomes “acting.” While there are a lot of important technical things to get right in a technology deployment, very few of them can fix the way that entrenched interests can exploit technology. If anything, technology is more often used by entrenched interests to avoid meaningful accountability. Rather than engage with the mechanisms of power that have influence over technology companies, most of the digital policy community agitates by drawing public attention to the details of the technology, like its privacy or security features. But, as discussed, most of the harms that technology can cause can’t be contained by the technology. It’s like trying to stop gun violence through gun design — it’s valuable, but neither the source of nor the solution to the problem. The digital policy community’s focus in the COVID-19 response has been more on comparative protocol security than about the likely impact of the technology’s use on public health or, even, patients’ rights.

The single largest determinant of success among various governments’ COVID-19 responses has not been military might, economic wealth or even executive power — it has been the trust of the governed. Technologies can help build or break that necessary trust. Until the digital policy community finds a way to focus its work on the structural, difficult task of building trustworthy systems, instead of theorizing technically ornate reasons to submit to untrustworthy ones, it will continue to be instrumentalized and delegitimized by those who benefit from the status quo.

An Intermission on Digital Governance

The ultimate vulnerability for democracy isn’t a specific technology, it’s when we stop governing together. The technological responses to the COVID-19 pandemic aren’t technologically remarkable. They are notable because they shed light on the power grabs by governments, technology companies and law enforcement. Even in the best of circumstances, very few digitally focused government interventions have transparently defined validation requirements, performed necessity analyses or coordinated policy protections to address predictable harms.

And, in the middle of a global pandemic, there are very few political levers to pull to stop them — many of those that do exist have been used to negotiate technological details, instead of to meaningfully challenge or prevent the power grab. Emergencies exacerbate the worst of those gaps, as the typical, good-faith panic to do something has created a huge number of high-profile technology hammers in a world largely without nails. Perhaps more dangerously, the transition from representation to expertise in government decision making, administered through procurement, narrows the political ambitions and the democratic legitimacy of the whole process.

Each of those power grabs could, instead, be negotiations — and negotiations held in courts and legislatures, as opposed to headlines or closed-door policy announcements.

If recent events have proven anything, it’s that everything can change and, in a lot of places, more needs to. There are no inevitabilities, not even technological ones — and we humans still experience the world through problems, not just user interfaces. Mature industries recognize the role of self-regulation in ensuring quality and sustainability, but they also recognize the role of meaningful public engagement and political support. The COVID-19 pandemic has made it painfully, globally clear that there aren’t techno-solutionist approaches to building trust in governance or any expertise that outweighs the value of public equity.

The more our institutional politics are procured like technologies instead of agreed through governance, the more we’ll feel the limits — and inevitable costs — of relying on technology theatre for progress.