Humanity will remember 2020 as the year of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is the year that people were expected to move their lives online and technology became the main outlet for connection outside the home. This made life more complicated as individuals and institutions had to quickly adapt to new online programs, navigating their personal and professional relationships through digital portals.

As the ability to choose what day-to-day interactions looked like became more limited, women felt the strains of the pandemic in highly gendered ways. Many lost their jobs because their work could not be adapted to online work-from-home positions, or had to reduce their time at work in order to take on the brunt of unpaid care work, including caring for children who were studying at home through virtual learning. By mid-year, Oxfam reported that 71 percent of Canadian women were feeling “more anxious, depressed, isolated, overworked, or ill” because of the additional unpaid care work they were expected to take on following changes from the pandemic.

As women struggled with these additional emotional, physical and financial burdens that exacerbated existing gendered inequalities, they also found themselves at the centre of what the United Nations has dubbed the shadow pandemic. When most countries began enforcing lockdown rules in the spring of 2020, reported rates of gender-based violence increased worldwide, especially the rates of intimate partner violence and technology-facilitated violence.

As the ability to choose what day-to-day interactions looked like became more limited, women felt the strains of the pandemic in highly gendered ways.

In Canada, front-line victim service workers saw both the the volume and the severity of gender-based violence surge. Because of pandemic-related restrictions, women were often trapped in the home with their abuser under stressful circumstances with limited access to their normal support systems or means of escape. Further expectations to work, shop and communicate online increased violence in digital spaces as more of women’s lives were directed online and abusers had more time online to perpetuate abuse.

Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence

Technology plays a complicated role in the shadow pandemic of gender-based violence. It acts as a potential outlet for women to seek support, but it is also being used as a tool to commit abuse against them and to enact gendered harassment online. It changes the ways that gender-based violence manifests, how it is understood, and the manner in which governments and organizations should support victims of this abuse.

Zoom-bombing and discriminatory harassment: Women have been targeted in their schools and workplaces where they have had no choice but to participate online. Research from Ryerson University’s Infoscape Research Lab examined early trends in Zoom-bombing — a form of harassment where the attacker posts offensive and shocking content to disrupt virtual meeting spaces. It found that most Zoom-bombings that were posted on YouTube were racist (25 percent), misogynistic (43 percent), homophobic (14 percent) or otherwise offensive. They were typically directed at female teachers’ classrooms. As this disturbing trend spread, women and other equality-seeking groups demanded that companies like Zoom develop safeguards and provide instruction on how to protect their workplaces from discriminatory online harassment.

The discriminatory nature of these attacks is nothing new. In 2018, Amnesty International’s Toxic Twitter report examined harassing tweets directed at women on Twitter, highlighting how women — in particular, LBTQ+ women, Black women and women of colour — face higher rates of abuse online, and face more attacks that focus their gender and other identity factors.

It is fair to say that women in general, beyond those interviewed for Amnesty International’s report, were already dissatisfied with large social media companies’ content moderation policies and procedures. More recently, with these companies reducing the number of content moderation employees at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, their frustrations were only intensified.

Zoom-bombing and other online forms of harassment cause severe emotional distress, heighten risks to women’s safety and deter women from engaging in online spaces. However, going offline to avoid abuse is not a realistic option today when almost all aspects of life have a digital component.

Image-Based sexual abuse: With restrictions on physical contact in place, many people have been trying new forms of online sexual activity. Some governments and centres for disease control even recommended that people engage in virtual sexual activity rather than in person. This activity can be a healthy addition to a person’s sex life and a novel way to safely connect with new sexual partners, but it also opens new avenues for exploitation when misused by abusers. In April 2020, the UK Revenge Porn Helpline saw a 98 percent increase in reported cases compared to the same month in 2019. Several months into the pandemic, the significant spike in numbers had still not abated, and the helpline saw higher numbers of “sextortion” (sexual extortion) cases targeting women than usual. Helpline employees feared that the pandemic had triggered an increase in image-based sexual abuse that was here to stay.

Online stalking: Another UK organization, the Paladin National Stalking Advocacy Service, reported a 50 percent increase in reports of stalking between March and June 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. Interviews with Paladin staff and clients reported that stalkers had changed their stalking behaviour during the pandemic. Their clients reported more technology-facilitated stalking and abuse by their stalkers, including increases in intimate images being distributed without their consent and fake social media profiles being used to impersonate them.

As women are required to rely more on online services and communication tools, their stalkers have additional avenues for perpetrating their online abuse. One woman Paladin supported suspected that her stalker had placed recording devices in her home. While she used to go to other people’s homes for respite from the spying, lockdown orders prevented her from doing so. Women who were reluctant to use certain technology out of fear that their stalker might use it to monitor them became even more socially isolated as in-person contact was limited and most communication moved to digital spaces that they did not feel safe to use.

These findings are just a sampling of documented and anecdotal reports of the recent increase in technology-facilitated gender-based violence.

Anti-violence Service Provision in the Technological Age of COVID-19

The changes in the ways that women experience violence require new forms of support at a time when service provisions are becoming more difficult to provide.

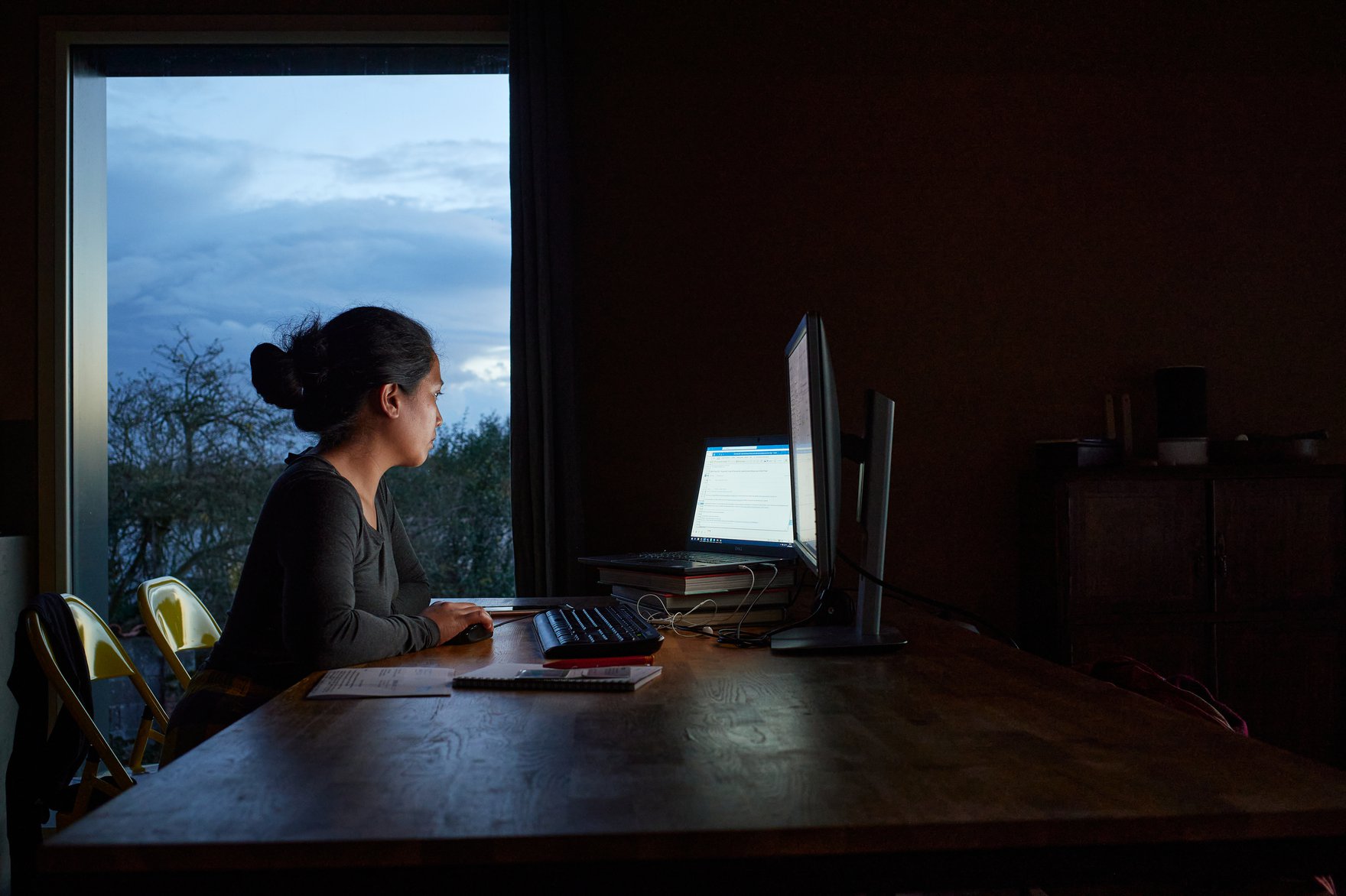

Technology plays a vital role in accessing services that support women who are being harmed by this online violence. With restrictive health guidelines in place, many organizations no longer offer in-person services and are finding it challenging to adapt to this new reality. Some organizations can reach their clients over the phone or the internet to provide supports, but this can be problematic for several reasons.

For one, women who are struggling financially may not be able to afford the technology needed to connect with service providers. Their phone plans may have limited minutes, texts or data that make longer conversations — such as those required to do comprehensive safety planning — cost-prohibitive, or they may not own a computer or have internet connectivity in the home; as well, many once publicly available computers or phones in places such as libraries or community centres have limited access or are closed altogether (because of COVID-19 restrictions). Women were economically disadvantaged prior to the pandemic and have become even more so in the last year, making it more difficult to afford the technology needed to access services.

Further, even if a woman has access to the technology needed to connect with service providers, if her abuser lives in the home and both of them are following the stay-at-home orders, it can be extremely difficult to contact anyone for help without being detected or overheard. Phones and computers can be used to track phone records or internet search histories that can alert the abuser that a woman is seeking help, putting her at risk of increased violence. Some organizations are promoting hand signals or code words so women can signal to the people they are speaking with over video or phone that they need help.

Finally, technology-facilitated violence can be especially difficult to address because of the technology involved. Front-line service workers with years of experience working with survivors of gender-based violence are struggling to keep pace with changes in technology and the tactics used by abusers. With this new proliferation of technology-facilitated violence, already overworked organizations are expected to navigate this novel form of violence with few additional resources. Organizations such as the Clinic to End Tech Abuse in New York City, have the technical expertise to identify and address problems, for example, the removal of stalkerware that has been downloaded onto a woman’s device, but most anti-violence organizations do not have the resources or expertise to fully support women who have been targets of technology-facilitated violence.

Looking to the Future

As these many issues collide, governments, social media companies and anti-violence organizations need to work together to better respond to the ways in which the use of technology — during the pandemic and beyond — impact and facilitate gender-based violence. The move toward online work has had dire economic impacts for women; systemic poverty makes them more vulnerable to violence and less able to access supports. Governmental responses to the pandemic must address the needs of women and the root causes of gender-based violence.

As technology-facilitated violence increases, social media companies need to be more responsive to the needs of women experiencing technology-facilitated violence and provide transparent and accessible avenues of support for those abused on their sites.

Front-line anti-violence organizations require increased resources and supports so they can provide the safety planning and intervention strategies (including those that address technology-facilitated violence) that are so desperately needed. Governments that care about ending gender-based violence should be investing in these organizations and working with them to develop awareness campaigns that can help educate people about what technology-facilitated violence is, how to prevent it and where to get supports if they have been targeted by it. They can look to existing models such as the Office of the eSafety Commissioner in Australia, who has been advancing a forward-thinking research and education agenda as well as providing on-the-ground supports for targets of technology-facilitated violence.

Ending gender-based violence requires a multi-faceted approach where governments, civil society organizations, technology companies and everyday people each have a role to play.