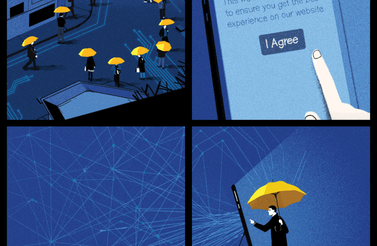

The biggest of the world’s digital platforms have come to be, in some ways, indispensable public utilities. In more remote rural communities, Facebook is the internet and Amazon is retail delivery. More widely, students, jobseekers, and journalists, among others, require access to Google’s educational suite, LinkedIn or Twitter just to do their work. Yet in the absence of any real accountability or transparency checks, those platforms assume some governing powers over the digital world. The pressure on governments to take corrective action appears to be on the rise; law makers and regulators are considering new measures, ranging from data protection and privacy legislation to boosting the enforcement of antitrust legislation.

For the most part, this “techlash” is taking the form of an anti-monopoly backlash. Still, it’s unclear what some of the proposed measures will actually accomplish. Already, various commentators have argued that compliance rules or fines — such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation or the $5 billion penalty the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) ordered Facebook to pay in their recent settlement — do more to support the dominance of the tech giants than to punish them.

Competitors who hack flagship properties are able to bleed off enough of the core business to keep any dominant player from maintaining their ascendancy merely by being the only game in town.

Compliance, whether real or nominal, may not be affordable for smaller organizations. Companies with deep pockets have the capacity to adhere to the letter — if not the spirit — of the law, which helps to clear the field of potential rivals. Upon the announcement of the FTC’s settlement order, Facebook’s former chief security officer, Alex Stamos, railed on Twitter: “The real threat to the tech giants is competition, not regulation, and everybody is missing what really happened today: Facebook paid the FTC $5B for a letter that says ‘You never again have to create mechanisms that could facilitate competition.’”

Author and activist Cory Doctorow argues that these unintended effects can be remedied if we reinstate the old development cycle of “adversarial interoperability,” in which prospective rivals hack the dominant technology of the day in order to create new products or services that easily plug in to those that are well-established, much against the wishes of the dominant business.

Conceived as a step beyond mandating simple data portability or even forcing the use of shared standards, adversarial interoperability, in Doctorow’s formulation, is both “judo for network effects” and at the heart of technology’s history of innovation.

Competitors who hack flagship properties are able to bleed off enough of the core business to keep any dominant player from maintaining their ascendancy merely by being the only game in town. The emergence of IBM-compatible personal computers or Apple’s development of products fully interoperable with Microsoft Office broke those nascent monopolies by offering options that were different or even superior (in price or features) but did not lock users out of the most commonly used systems of the time.

According to Doctorow, failure to amend or overturn laws that stifle competition, in particular, those around patents, anti-circumvention and tortious interference — anything that makes it illegal for third parties to bypass digital locks or reverse-engineer in pursuit of interoperability —will keep the vertically integrated walled gardens of the tech giants intact and leave consumers with few alternate choices.

So far, the most prominent voice to express skepticism about this approach is Evgeny Morozov. While he has not formally responded to Doctorow’s well-known position, he did make what seems like an oblique criticism: “Who is more populist: proponents of Big Tech who argue that the digital giants will rid us of all problems, including capitalism & politics — or their opponents who dream of small, competitive tech, convinced that humane digital capitalism will rid us of imperialism & exploitation?”

The “dream” so scornfully dismissed here is a creator’s take on this issue. On the surface, Doctorow’s advocacy for adversarial interoperability reads as a brief for business reform: the language of monopoly-busting virtues (competition and consumer choice) pepper his writing on the topic. And shifting the regulatory focus from the corporate entities themselves to the sources of their power (“fix the Internet, not tech companies”) is a clever departure from the usual calls to break up these massive conglomerates.

But there is an element of mythmaking in this prescription for bringing big tech to heel, which Doctorow self-identifies as his “techno utopian” streak. His recurring appeals to a narrative of technological innovation fuelled by brash upstarts laying claim to the turf staked out by the incumbents is a version of the classic underdog story. And his nostalgia for “a more civilized age” in which muscular competition determined the winners rather than the entitlement of privileged elites bears an unfortunate resemblance to populist tropes about a lost golden age.

When Doctorow declares “we can fix the Internet by making Big Tech less central to its future,” there is an underlying suggestion that digital monopolies are bad mostly because they are antithetical to the free flow of information and the remix-or-repurpose ethos of hackers and creators. They have corrupted his ideal of the internet as a space of creative freedom.

Adversarial interoperability — once the tools of the proverbial “Davids” — could just as easily become the tool of the “Goliaths.”

Romanticizing this ethos reveals some interesting blind spots. Adversarial interoperability — once the tools of the proverbial “Davids” — could just as easily become the tool of the “Goliaths.” It’s already happening in some areas — the open-data and open-source-code arenas come to mind.

An interesting example of this can be found in the health care space, where the botched digitization of medical record-keeping has created a nightmare. Locked into multiple, proprietary systems, the siloed patient data is inaccessible to those in need of it most, while often being strip-mined for profit by data brokers.

Interoperability has long been on the table as a possible reform in this area, and finally governments are imposing standards for medical record-keeping. Yet the situation is seen as so intractable that when Apple (hardly, the typical upstart outsider) ventured into this space with its personal health records app, they were seen as the white hats who would finally disrupt this dysfunctional ecosystem rather than a leviathan coming in to feed. Giving consumers what they want by moving into the turf of the dominant players was never solely the province of underdogs, but it does seem to magically confer that aura.

It is also worth noting that the world view behind techno-utopian visions was (and still, in many ways, is) upheld by a relatively homogenous group: mostly male, mostly English-speaking and scientifically literate, and in possession of enough skill and wealth to easily access and derive value from the digital world. The cherished ideals of openness and the free flow of information are not neutral or universal but rather the value system of the very specific — and powerful — group. The disenfranchised relate to technology and the internet in ways that are difficult to imagine from a tech insider’s perspective.

These elements of Doctorow’s theorizing can only be a red flag to Morozov. Both of these critics have clashed before (rather spectacularly) on the question of technology’s potential as a force for human liberation.

Given that Morozov has long challenged what he deems Doctorow’s propensity for generating “eloquent theories of the internet,” it is predictable that he would reject a corrective that both relies on the logic of capitalism and invokes nostalgia for an idealized past and a utopian vision of a kinder, better technocracy. For Morozov, such solutions put the cart before the horse: “The rise of Big Tech is a consequence, not the cause, of our underlying political and economic crises; we will not resolve them merely by getting rid of the Big Tech or constraining their operations.”