The debates about whether Canada did too much or too little to respond to the 1970 October Crisis, the 1985 Air India bombings or the 9/11 terrorist attacks were tough enough. But such questions about national security approaches are about to get harder still.

That’s because today’s debates must consider not only what states are doing but also corporations, including social media companies.

Uncovered by The Wall Street Journal, Facebook’s practice of exempting high-profile users from its content restrictions reveals that today’s true front-line censors are social media companies, not governments. Platforms have immense power. They can interfere with elections by, for example, sidestepping spending limits. They can sow divisions and promote the interests of foreign governments, including those who oppose democracy. We need to ensure that these multinational giants are more transparent and accountable in the ways they regulate and amplify conduct.

And although the answer might seem obvious, in light of recent revelations about Facebook from The Wall Street Journal and 60 Minutes, the perils of regulatory gaps in platform governance are evenly matched by the dangers of overreaching with policy in an attempt to address them. Finding solutions will be neither easy nor quick.

Another question for national security is how to balance protections against rights and freedoms. Democracy in Canada has never been a matter of simple majority rule. We must protect the rights of dissenters, minorities and Indigenous peoples and be very careful to only limit rights in a transparent and justified manner.

A case in point: Canada’s diverse Muslim minorities are caught in a bind where, on the one hand, they have at times been profiled as potential security threats but, on the other hand, been under-protected from terrorism, as seen in the 2017 Quebec City mosque shootings and the 2021 London, Ontario, vehicle attack.

A security apparatus that focuses on Muslims as a security threat will be in a poor position to target terrorists motivated by far-right ideologies before they strike.

The historical record shows that national security laws can be costly to democracy, especially if enacted quickly and without full debate. That’s why our collective response to threats to national security must be more nuanced than simply more laws or prosecutions or the listing of a few far-right groups as terrorist groups. Canadians should be encouraged to be both citizens and critical consumers of news and information.

Yet another difficult question to address is how to encompass climate change and health security within national security. It was inevitable, in a time of global warming and pandemic, that these problems would become viewed as pressing national security threats. That’s as it should be. But this shift, in an increasingly perilous global environment, also raises the possibility of excessive securitization. If everything is a matter of national security, then nothing may be. Even as we face these real new risks, we should be careful to not unnecessarily securitize health, education, social cohesion and the economy.

Environmental and Indigenous rights protesters, for example, must not be targeted as national security threats. The provincial government of Alberta has in the past mimicked the approach of Beijing-controlled Hong Kong in defining “foreign interference” as a security threat. The Alberta government recently held an inquiry into the involvement of “foreign organizations and funding” into “anti-Alberta energy campaigns.” This is not a matter of national security, and should not be treated as such.

What may be a matter of national security, however, is the current COVID-19 pandemic. The Alberta government’s approach to COVID-19 demonstrates the dangers of using ideology and legitimate concerns about the economy to trump the need for nuance, education and evidence in defining public security policy.

The case of Alberta demonstrates yet again the risk of politicizing and simplifying national security matters. And Alberta is not the only offender here. Canadians had a right to expect continued briefings by public health officials, even during the recent federal election. They did not receive them.

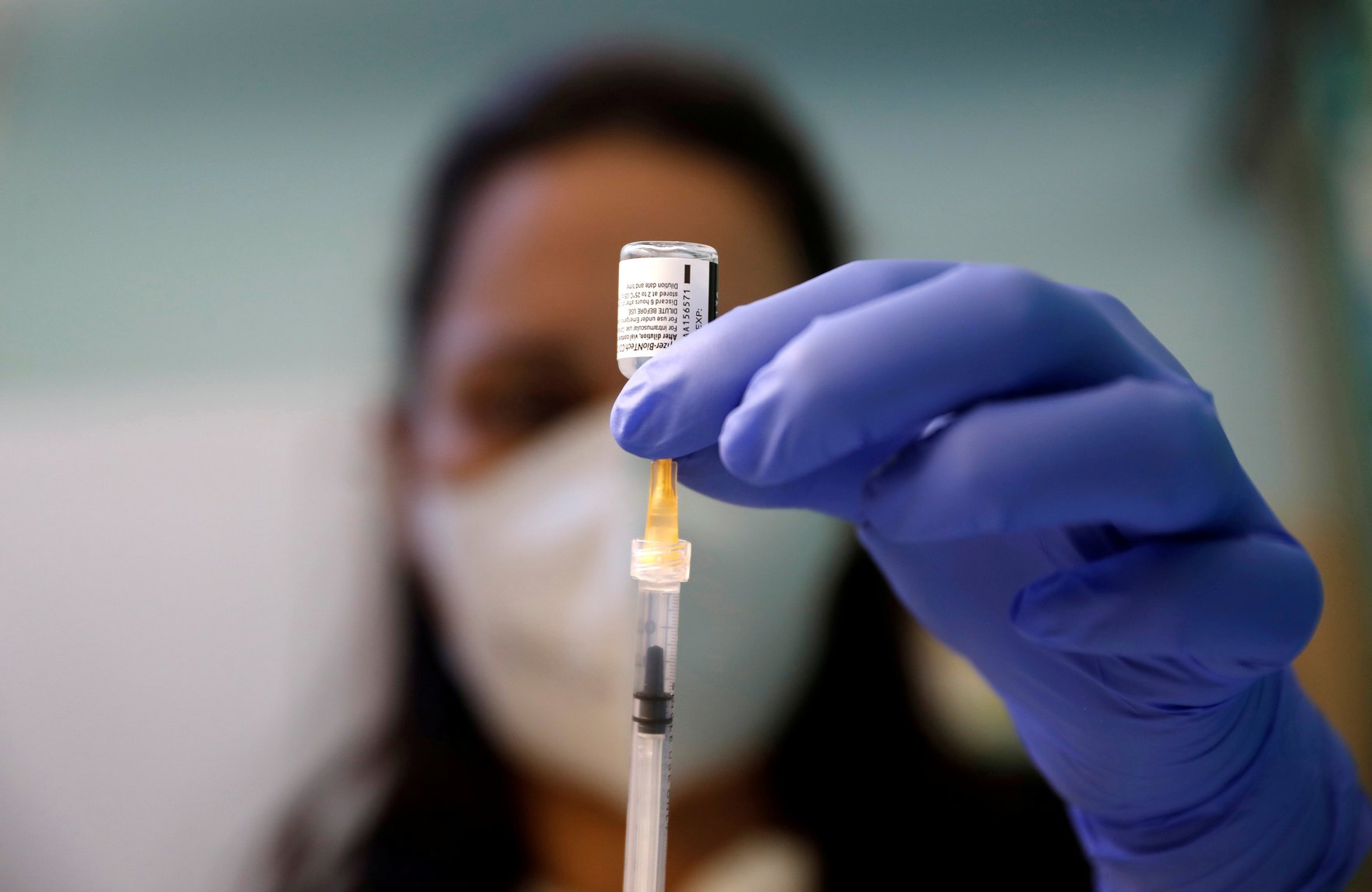

Those who oppose vaccine mandates arguably pose a security risk to the public health care system, which can be overwhelmed to the point of collapse. Ultimately this is a matter of evidence, not ideology. Yet even so, the vaccine-hesitant have rights that must be considered. So far Canadian courts have ruled against challenges to vaccine mandates and they play an important role in providing checks and balances to our national security policy.

The point is that we should not assume that national security and rights must always be in conflict. Softer national strategies, such as education and persuasion, can in some contexts uphold rights and be more effective than harder, more coercive instruments, including legislating that everyone must be vaccinated.

Reconciling national security with democracy has always been among our greatest challenges. It will become even more difficult as we face a growing list of security threats. Mistakes are inevitable. We need to learn from them, as we have in the past. It’s worth remembering that Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms itself, and the checks placed on our civilian security intelligence agencies, stemmed from lessons learned from the overreaction of the October Crisis.

Tempting though it may be to seek easy solutions, the truth is that there are none. A good start, instead, would be to help ensure that Canadians become more literate about the need for democratic checks and balances, as well as security readiness, to co-exist and evolve in tandem.