here is a striking blue building on Toronto’s eastern waterfront. Wrapped top to bottom in bright, beautiful artwork by Montreal illustrator Cecile Gariepy, the building — a former fish-processing plant — stands out alongside the neighbouring parking lots and a congested highway. It’s been given a second life as an office for Sidewalk Labs — a sister company to Google that is proposing a smart city development in Toronto. Perhaps ironically, the office is like the smart city itself: something old repackaged to be light, fresh and novel.

“Our mission is really to use technology to redefine urban life in the twenty-first century.”

“Our mission is really to use technology to redefine urban life in the twenty-first century.”

Dan Doctoroff, CEO of Sidewalk Labs, shared this mission in an interview with Freakonomics Radio. The phrase is a variant of the marketing language used by the smart city industry at large. Put more simply, the term “smart city” is usually used to describe the use of technology and data in cities.

No matter the words chosen to describe it, the smart city model has a flaw at its core: corporations are seeking to exert influence on urban spaces and democratic governance. And because most governments don’t have the policy in place to regulate smart city development — in particular, projects driven by the fast-paced technology sector — this presents a growing global governance concern.

This is where the story usually descends into warnings of smart city dystopia or failure. Loads of recent articles have detailed the science fiction-style city-of-the-future and speculated about the perils of mass data collection, and for good reason — these are important concepts that warrant discussion. It’s time, however, to push past dystopian narratives and explore solutions for the challenges that smart cities present in Toronto and globally.

The smart city model has a flaw at its core: corporations are seeking to exert influence on urban spaces and democratic governance.

To understand the questions that Sidewalk Labs is forcing policy makers to grapple with, it’s important to understand some of the context around the proposed Toronto development. Be forewarned: it’s an odd-couple scenario with a complicated backstory.

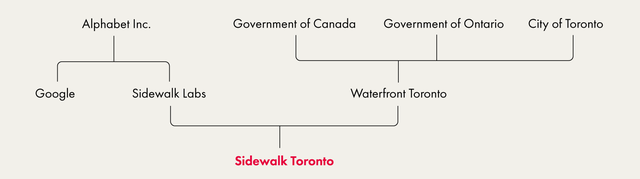

Sidewalk Toronto is a joint venture smart city project created by Sidewalk Labs and Waterfront Toronto.

Waterfront Toronto is a not-for-profit corporation leading the renewal of Toronto’s waterfront. Three orders of Canadian government (federal, provincial and municipal) are equal, non-equity-share sponsors and have provided the corporation with seed capital to transform 2,000 acres of brownfield waterfront land. A board of directors, appointed by the three levels of government, oversees the strategic direction of the corporation, which began seeking a partner to help develop a small 12-acre plot of land, known as Quayside, in early 2017.

Later that year, Waterfront Toronto named Sidewalk Labs the winner of the request for proposal (RFP) process. A recently signed agreement has solidified that Sidewalk Labs will invest US$50 million to create a plan for Quayside, and to develop products and services there to sell to other cities globally.

To do this work, Sidewalk Labs and Waterfront Toronto have created a new legal entity — Sidewalk Toronto, a limited partnership. So far, no land has changed hands. Approval of the plan for this 12-acre plot will be required from the Waterfront Toronto board, Alphabet (Sidewalk Labs’ parent company) and Toronto City Council, as well as other levels of government as required. The plan, called a master innovation and development plan, is expected to be complete by spring 2019.

Over the last year, Sidewalk Toronto has hosted a series of public consultations focused on urban life staples, from mobility to housing. And, most recently, Sidewalk Labs opened a Toronto headquarters — the blue building from this article’s introduction.

As a whole, the grand marketing vision for Toronto’s neighbourhood of the future is expansive and data driven, and speaks to issues of affordability, resilience and sustainability. It features underground garbage robots, autonomous vehicles, snow-melting sidewalks and more. While many of the features rely on the use of new technology and data to create responsive and adaptive places and spaces, other key features — modular housing and wooden buildings, for example — do not rely on new technology at all. The proposal also makes persistent mention of the need for access to more than the initial 12-acre plot of land for the innovations to be realized at scale. This nods to a possible play for a larger stake in the development of Toronto’s prime waterfront real estate.

Setting the particulars of this deal aside, there is definitely a case to be made for rethinking cities. Ken Greenberg, planner, author and adviser to Sidewalk Labs, puts it this way: “Our systems are strained; established ways of doing basic things are stretched to the limit and beyond...The Sidewalk partnership may just provide the catalyst, R&D resources, and the time and space we urgently need to help us make the leap in critical areas.”

While Greenberg’s definition of the problem is correct, the solution that’s on the table for Toronto should be considered somewhere on the spectrum of highly contentious to full-fledged democratic emergency. This piece will outline a series of approaches to address the challenges associated with Sidewalk Toronto’s vision for Quayside — or with any other smart city.

Commit to Open Procurement and Contracting

In February, The New York Times editorial board wrote that “we find ourselves at a moment of profound uncertainty about the role of technology in our lives, the influence of the tech companies and the correct direction of public policy to address all this change. We’re effectively asking technologists and policymakers to do so much — to secure our elections, to reinvent our business models, to educate and entertain and safeguard ourselves and our children, to protect us from extremists around the world. We expect all of this, across 200-plus nations and uncountable cultures, while also aspiring to privacy, transparency and prosperity.”

As the public becomes more aware about the impact of technology, they also grow more alert to related dangers that privacy and surveillance experts have been ringing alarms about for decades. This recent awakening should give cities permission to take decisions around smart cities seriously and slowly, and to demand open information about them. Procurement is a good place to start.

In Toronto, the opposite has played out. For nine months the public was kept in the dark about details of the deal, despite promises of an open and collaborative process and public pressure. Recently, however, both agreements that the organizations have signed were released. The newest agreement details the nature of the working arrangement between both organizations and some high-level language around data use. Still, the agreements are short on specifics, and they fail to impose baseline requirements around control of public data and publicly owned digital infrastructure.

Waterfront Toronto went out on a limb with this procurement in the name of innovation, asserting an unchecked assumption that Toronto residents want this type of smart city development to occur. A City of Toronto report reveals that six initial applicants bid in the RFP process, and that three were short-listed for the final round. While the criteria for selection were included in the RFP, Waterfront Toronto hasn’t published any additional information about how the final decision was made. Sidewalk Labs’ persistent declaration that it chose Toronto adds to the grey. Other cities can start to take notes here: don’t go down any smart city track without public buy-in on what is being asked of a vendor or partner. Start consultation at the RFP stage and define the terms of these deals before the bidding begins.

The agreements are short on specifics, and they fail to impose baseline requirements around control of public data and publicly owned digital infrastructure.

Mark Wilson, former chair of the board of Waterfront Toronto and current Waterfront Toronto digital strategy advisory panel member, sees this project as an opportunity to evolve the approach used in technology procurement. For Wilson, Sidewalk Toronto presents a chance to improve oversight and intentional design for municipal technology purchasing. “We need to acknowledge that many of these systems will be built and operated by the private sector for governments,” he says. “We can find ways to ensure public control of these systems, to make sure they achieve public benefit and integrated service delivery, while avoiding vendor lock-in.”

Public control, however, can only be achieved with an educated public.

Embark on Intensive Public Education and Consultation

Remember the era of public safety campaigns — fire safety, seat belts, atomic bombs? Governments need to do this kind of awareness building around data and technology too.

Consider that every time someone boards a plane, no matter how many times they've boarded a plane before, an airline steward — a human — walks them through the safety process. Similar interventions are necessary for people to understand their data and how it can be used.

To date, Sidewalk Toronto’s consultations have focused on urban issues such as mobility and housing. The community engagement efforts taking place inside the bright, blue building on the waterfront are commendable, but they come with a side of marketing. Residents can drop by and explore smart city building materials, test new technologies and ask questions. This kind of public engagement can be a complement to residents’ participation in the democratic process with government, but it’s not a replacement.

That’s the thing about Sidewalk Toronto: it isn’t the government. It’s a vendor that is closely tied to a global technology giant. That reality and identity haven’t been highlighted in the public engagement and consultation processes. Quite the opposite. With constant references to “improving quality of life,” Sidewalk Labs is co-opting the language of government to serve its business purposes.

“Data governance is a complex issue that is out of reach for many; public and private institutions need to create the opportunities for these necessary discussions.”

The lesson for other cities here is clear: engagement theatre on urban issues is part of the smart city vendor playbook. Where there should be public education on the technology, there is instead the diversion of attractive illustrations of improved urbanism. But basic questions around the fundamentals of a smart city remain: How does the Internet of Things work? How is it kept secure? How does surveillance work? How will data be shared with law enforcement? Which laws will govern smart city data — regardless of their vintage or readiness? How might the residents’ data contribute to intellectual property? Will consumer protection laws protect smart city residents?

Right now, residents don’t have a fighting chance of exerting their opinion on the smart city through public consultation, because these questions haven’t been answered, and the issues haven’t been explained or taught.

According to Amira Elghawaby, a journalist and human rights advocate, “data governance is a complex issue that is out of reach for many; public and private institutions need to create the opportunities for these necessary discussions.”

Well-funded and intensive public education and engagement programs present opportunities for government and technology firms alike to ensure human rights and economic development are considered alongside each other.

That said, how these programs are structured and scheduled matters. Both Brazil and Taiwan, Province of China, for example, had deeply deliberative approaches that provided the support needed for the complexity of smart city issues. Brazil conducted an intensive public process to create the Brazilian Internet Bill of Rights, and Taiwan created new and expansive ways to consult on technology issues both online and in person. Engagement will always be influenced by local factors, but whatever process is selected must reflect a deep commitment to education alongside engagement. This commitment to public education is critical in the face of the heavily commercial public relations and marketing efforts that are part of the smart city industry’s agenda.

Right now, residents don’t have a fighting chance of exerting their opinion on the smart city through public consultation, because these questions haven’t been answered, and the issues haven’t been explained or taught.

The Canadian government is making some of the right moves to support public education and engagement around smart cities, but they come late in the game. Recently, Canada announced funding for community capacity building on smart cities, as well as a national consultation on a federal data strategy. The framing of the consultation is narrow (on data) and industry-heavy. Further, the federal government of Canada, the provincial government of Ontario and the City of Toronto were all party to the RFP process for Sidewalk Labs. They had enough lead time to start properly engaging and educating residents, and they squandered it. Arguably, a number of avenues already exist to help support education campaigns on smart cities — public libraries have long been considered the civic institutions best positioned to convene and lead the work. They’re already doing what they can, but with dedicated funding, they could do more and then feed their findings back into federal policy creation.

Even with a few good programs in the works, certain areas of the smart city discussion are still seriously hindered by a lack of public education — and data management is at the top of the list.

Think of Civic Data Management as a Government Responsibility

Data collection, privacy and surveillance are at the centre of discussion around Sidewalk Toronto. Consistently, however, these discussions begin with “what will you do with my data?” rather than with “why do you need my data at all?” It’s as if surrendering data to the private sector is required. It’s not.

It’s vital to find more precise language for the data used in a smart city in order to talk about it together. Personally identifiable information is one thing. Aggregate and anonymized human behavioural data about how people move around in cities is another thing. There is also environmental data (weather, pollution) or geospatial data (maps, facility locations), among many others. Each data type and context require a different type of conversation around how the data might be used by government, how it might be commercialized, and how it might be made open, shared, or kept closed.

In terms of a discussion about who owns city data, Teresa Scassa, a CIGI fellow and the Canada Research Chair in Information Law and Policy at the University of Ottawa, has recently written that the concept of legal “ownership” doesn’t fit the bill when discussing data. She also describes many cases of data hand-off from residents as surrender rather than consent.

Several data governance initiatives offer some guidance on how to tackle problems related to data collection and use.

“We grant government the right to collect very personal data about us to improve the public and personal good. This is a fundamental part of the social contract. We don’t have that relationship with the private sector.”

At a legislative level, the recently enacted European General Data Protection Regulation is instructive — among its other provisions, including harsh corporate penalties for abuse, it seeks to improve consent mechanisms and give individuals more power to define how their data is used. At the community level, Decode, a European data project, “provides tools that put individuals in control of whether they keep their personal information private or share it for the public good.”

In Canada, for the Sidewalk Toronto project, the idea of a data trust has been raised as a possible solution for the management of civic data. Data trusts might provide a short-term data management approach, but they also require new levels of civic participation, which are challenging to meet for residents already burdened with other realities of life.

According to Renee Sieber, associate professor in the Department of Geography at McGill University, data trusts aren’t likely to be a cure-all.

“We grant government the right to collect very personal data about us to improve the public and personal good. This is a fundamental part of the social contract. We don’t have that relationship with the private sector. We don’t know what they will or could do with our data — there are no mechanisms for us to manage what they are collecting about us,” she says. “This is why the idea of a data trust is attractive for the private sector, but not for the public sector — we already have a social contract with government, it includes mechanisms substantiated in law and a political process for influencing that collection and control.”

Shannon Mattern, a professor at The New School in New York, provides an important reminder that data is but one ingredient to use in building cities of the future: “The kernel of potential goodness in all of these smart city initiatives is to use data more thoughtfully. But it generally goes too far because the data narrative goes too far. Data become a panacea instead of one tool within a set of many,” she says. “Data-obsessed models present an oversimplified approach to urbanism.”

Recognize Smart Cities as a Political Issue, Not a Technology Issue

A long list of failed smart cities is often trotted out to demonstrate the folly of the techno-utopia vision — from the Songdo International Business District in South Korea, to the Epcot Center in Florida, to Masdar City in Abu Dhabi. There are, however, new approaches to technology management that stand as examples of improvement. They include the use of participatory models that engage residents in decision making and data stewardship. While most of these models are not set in the fully entrenched type of smart city real-estate development that Sidewalk Toronto represents, they make strides in defining best practices for smart cities. Francesca Bria, the chief technology officer for the city of Barcelona, is spearheading one such initiative.

“We must challenge the current narrative dominated by Silicon Valley’s leaky surveillance capitalism and dystopian models...”

In 2015, Ada Colau, a progressive candidate, won the mayoral election in Barcelona. Her campaign has been described by some as a response to the corporate smart city movement. Under her leadership, Barcelona is instituting policy to guarantee not only open technology systems as a procurement requirement, but also resident control of data and technology-driven civic participation. In another nod to civil society at the centre of the smart city, Barcelona’s public libraries are being brought in to support the open data program component, an approach that Canadian community technology leaders such as Mita Williams have wanted for years.

Barcelona demonstrates an important distinction for smart cities: smart city development is not a technological decision, but a political one.

As Bria explains: “We must challenge the current narrative dominated by Silicon Valley’s leaky surveillance capitalism and dystopian models such as China’s social credit system. A New Deal on data, based on a rights-based, people-centric framework, which does not exploit personal data to pay for critical infrastructure, is long overdue.”

Political will was critical to Barcelona’s story. Political change — election of a progressive leader with a vision to create a resident-led technology movement — came before technological change.

Adopt an Agile Policy-making Process

Smart cities don’t fit neatly into existing legislation or policy at any level. As a result, corporations seeking to exert their influence on urban spaces are doing so in a policy vacuum. The technology and data governance frameworks that govern most cities were created prior to the internet era and aren’t designed to manage the emerging issues created by pervasive data collection and connected technology.

Laws need to be updated to protect privacy, security, sovereignty and more. These changes tend to happen slowly, which is generally the right thing with the law. But to address the range of urgent governance challenges that smart cities pose, a set of complementary actions can be taken to create workarounds and stopgap models. If they’re bad or don’t work, they can be revised or dismantled entirely. Agile policy creation is something all governments will need to start getting comfortable with as technology development in the private sector continues to move faster than policy.

Anthony Townsend, author of Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia, explains that the baseline operational models for cities — everything from how public records are organized to information-handling principles — haven’t been revisited in decades. He suggests that cities should create digital master plans to direct overarching technology policy that can support a city’s general strategic planning efforts.

The technology and data governance frameworks that govern most cities were created prior to the internet era and aren’t designed to manage the emerging issues created by pervasive data collection and connected technology.

Within such a framework, there would also be opportunities to create collaborative approaches to share infrastructure with other cities. Software code, which is digital infrastructure, has a key difference from traditional physical infrastructure such as bridges and roads — it can be replicated and shared around the world.

“[Cities] could consider developing a model of ownership and licensing, perhaps something like Creative Commons licences, that would enable the sharing of technology under flexible terms or something similar to a patent collective where the tech could be pooled and shared under agreed terms,” says Myra Tawfik, a senior fellow at CIGI, and a professor of law and the EPICentre Professor of Intellectual Property Commercialization and Strategy at the University of Windsor.

“They can come together as cities, work with a shared legal team and draft a model agreement on fair and reasonable terms designed for the benefit of residents and humanity.”

Creating data standards to support this type of shared digital infrastructure and interoperability is another track of work to consider. Such efforts have been underway for years already but could be energized with a broader set of stakeholders at the table and with an increased sense of urgency.

Sidewalk Toronto certainly provides that urgency.

This story is set in Canada, but it should prompt policy makers everywhere to roll back the bright, distracting wrappings and playful narratives of smart cities. The approaches that this article outlines — open procurement, public education and engagement, responsible data management, a focus on local democracy and an agile policy process — aren’t easy, but they provide a path forward from the dystopian smart city.

Technology can be well deployed in cities — not to track, monitor, profile and profit, but to support local needs, improve urban environments and support democratically informed policy.

More from Bianca Wylie on Smart City Development

The opinions expressed in this article/multimedia are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of CIGI or its Board of Directors.