As long as the outbreak of COVID-19 continues, societies around the world will depend on a handful of global technology corporations. Daily life — including friendships, relationships, family connections, education, employment, healthcare, finances and much more — will be mediated by platform companies such as Google and Facebook that see our human interactions and relationships as content to be moderated, and as sources of data to be monetized. Amazon is already becoming a primary source of supplies, delivering food and other goods to our door. We are coming to rely increasingly on platforms for our every social and material need. This is the future that Big Tech has long wanted, but could only dream of until now.

In some ways, the pandemic could lead to a renewal of community and solidarity and a decline of individualism. But it also risks much of that renewal playing out on privately owned internet platforms — even in a time when capitalism looks to be on hold in the face of a serious threat to public health. It doesn’t have to be this way. Together, individuals, policy-makers and governments need to confront the power that private companies now hold through their control of social infrastructure.

Social Bonds for Profit and Control

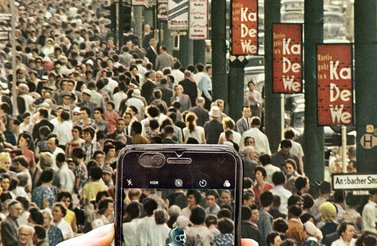

COVID-19 has thrown into sharp relief the fact that, in the West, institutions that supported community and solidarity and the social ties that made them viable have been undermined in pursuit of the privatization of government functions, the expansion of self-regulating markets and the advancement of individualism. In recent years, physical spaces of community and solidarity were being replaced or supplemented by virtual sites of social interaction. Communications and conversations with family and friends take place on social platforms such as Facebook, Instagram (also owned by Facebook) and Twitter. We use video conferencing services like Zoom and Skype (owned by Microsoft), to connect with each other for work and leisure, and share videos on YouTube (owned by Google) and TikTok.

At a time when social ties need to be rebuilt, the coronavirus is accelerating this digitization of society. With social distancing, school shutdowns and countries around the world in lockdown, much of the social and economic activity that was still taking place “offline” is now being forced into the virtual sphere. People are increasingly reliant on internet services for work, community and social interaction.

Long before COVID-19, physical spaces of community and solidarity were being replaced or supplemented by virtual sites of social interaction.

Although digital platforms promise interpersonal connection and form the technical backbone of our online society, they are, first and foremost, spaces driven by capitalist logics of enclosure, control and profit-making. They are owned and operated by private corporations accountable to shareholders with voracious appetites for revenue. They have aggressive strategies for growth and global dominance. Their business models — variations on “surveillance capitalism” — involve appropriating and commodifying human relationships, manipulating people for profit and reconstituting collective social goods like privacy as things that can be individually bartered in exchange for access to friends and family.

Through society’s embrace of social platforms as sites of interpersonal communication and connection, global capitalism has encroached upon areas of life that it could never have reached before. A global pandemic — seemingly catalyzing a shift toward collective thinking and economic and social intervention by the state — could paradoxically result in ever greater parts of society captured by capitalism: individualized, surveilled, manipulated and mined for profit.

Platform Power and Social Infrastructure

Like all technologies, platforms are political. Control of social infrastructure gives platform designers and operators power to shape society according to the ideologies of techno-capitalism and the interests of the companies that own them. Libertarianism, individualism, faith in the free market, and cyber-utopian beliefs that more technology will lead to better society have shaped much of today’s internet services and online platforms. Tech companies typically pursue “disruption” (loosening or dismantling existing societal bonds and building new relationships that depend on the tech industry’s services) and “scale” (chasing ever more users and more of their data from which profit can be extracted), and embed those particular logics into routine platform design decisions. Platforms decide what users see according to their commercial priorities of scale and profit and their duties to their shareholders. They set the rules for discussion, discourse and communication. They even influence power relations between their users. Zoom, for instance, could until recently tell your boss what you were doing while working, allowing them to track whether you’re using a different app while on a call. Moving workplaces online greatly extends the potential for surveillance of employees, strengthening the position of employers and platform owners and upholding the power of capital over labour — all during a crisis that will shape much of the future of labour and production policy.

It is no surprise, then, that social platforms typically encourage passive engagement with content supplied by their algorithms, “clicktivism” in place of collective action, and disengagement with the wider world. In practice, they often foster division, aggression and alienation and allow racism, white supremacism and misogyny to proliferate. Meaningful connections are possible, but they are only a second-order issue in a profit-making business model.

Platform companies have leveraged their position in society to take on an ever-greater number of quasi-public functions, exercising new forms of unaccountable, transnational authority. Google, Facebook, Twitter and others play key roles in elections and democratic processes. They decide what they flag as fake news and who they consider to be a public figure or politician. Facebook has been implicated in ethnic cleansing and platforms allow racism, white supremacism and misogyny to proliferate. Amazon chooses to help US Immigration and Customs Enforcement with deportations (although workers’ movements within the tech industry have pushed back strongly against this). In many countries, Facebook and Google are so ubiquitous as to essentially be the internet for most people.

Even in normal circumstances, the scale of a few dominant platforms leaves ordinary people with little choice but to use them. Now, the COVID-19 crisis has propelled us to the point where these platforms are embedded even more deeply in our lives, and further entrenched in our social and political structures. All the more reason why these platforms — and the power that they confer — should not be concentrated in the hands of a few global corporations with commercial interests at heart.

Building a New Platform Ecosystem

It is now clearer than ever that we need to rebuild bonds of community, solidarity and society. We need to re-envision our society and our digital economy, with new institutions, new structures and new spaces for communication and connection. The platform model of online services is not itself a problem, but we need to radically rethink how platforms are organized and how they operate. This step, of course, is only the first of many in the process of structural platform governance reform.

A new platform ecosystem must not leave social infrastructure in the hands of private tech companies. It must include digital spaces of interaction and communication where profit isn’t the dominant logic, where people aren’t subject to surveillance and manipulation, where community and solidarity can develop free from capitalist control, and where the needs of society are prioritized over the interests of capital and shareholders.

What could these future platforms look like? To begin to answer that, we need to consider four things: ownership, structure, function and governance.

Ownership: The current ownership model of social platforms is incompatible with true social renewal. Instead of maximizing profits, social platforms should be owned and operated to benefit society. To make that possible, we need to develop workable models of social ownership for the social platforms of the future — whether they are public or state-owned, cooperatives formed by their users or in some other form.

Structure: We must be careful not to lose the benefits of the open internet as we move toward social ownership. But scale brings its own problems — fuelling expansion, and making it difficult or impossible to manage the sheer volume of information being processed and the number of users involved — and confers potentially great power to shape the world. Instead of global platforms operating at scale, we need multiple local, regional, national social platforms that connect in much the same way as we have multiple local, regional, national telecommunications networks that connect, and with similar requirements for interoperability across borders and organizational boundaries. This connectedness and interoperability would allow communication across platforms and eliminate the network effects that have helped a handful of platforms to dominate digital markets. These new downscaled social platforms could vary in size — from small groups of neighbours, friends and relatives, to larger groups of people with shared interests, or even whole communities and countries. Some of these future platforms could be configured as public utilities; some could be set up by other organizations for their members or by loosely coordinated groups acting together.

Whatever alternatives to privately owned platforms emerge, they will be resisted, appropriated and potentially destroyed. But that is not an insurmountable challenge.

Function: We need spaces that prioritize communication and meaningful connection over passive engagement and that do not exist to extract profit from our social relationships. Such spaces cannot be created unless strong privacy regulations are put in place across borders. Existing legal frameworks are not enough. Even the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, arguably the most comprehensive in the world, operationalizes privacy as an individual right and leaves users largely responsible for their own protection, despite overwhelming structural challenges. Where advertising and algorithmic personalization are used, these must be subject to strong constraints and oversight. Behavioural advertising should be prohibited; alternatives exist.

Governance: To help empower people instead of corporations, future social platforms must be democratic, transparent and accountable. Democratic and inclusive platforms require a framework that involves their users in decisions. Operating at a smaller scale can allow rules and accountability mechanisms to be determined collaboratively and democratically by each platform’s members. Their decisions and policies should be made accessible through publicly available charters and transparency mechanisms by which users can access explanations and justifications for actions that affect them. An overarching legal framework could provide the structure for a more democratic and accountable ecosystem of platforms to emerge and remain sustainable.

In this model, interoperability unlocks new possibilities. Different forms of social ownership could be adopted on different platforms, with each operating according to the wishes of its members. Expanded data portability standards would allow members to move between platforms — some platforms could be open for anyone to join; others could be closed or limited to invitees. At the same time, members of each platform would be able to communicate with those of others (or, indeed, to limit the reach of their communications). The result could be a thriving ecosystem of new social platforms co-existing alongside each other, socially owned and operated for the benefit of their members, without the problems of scale or the network effects that tend toward monopolization.

There is much work to do on the fundamentals of a functional social platform ecosystem before it becomes a reality. Although various initiatives in recent years have produced promising proposals, none has yet gone as far as to reinvent a workable new model. Whatever alternatives to privately owned platforms emerge, they will be resisted, appropriated and potentially destroyed. But that is not an insurmountable challenge. A new ecosystem must be resilient in the face of a corporate pushback.

Now more than ever, in an age where social relations are largely mediated, captured, moderated and manipulated for profit, we need to rebuild the roots of community and solidarity. We must build socially owned, pluralistic, democratic and privacy-preserving social platforms, services and communications channels that foster community and connection instead of corporate profit and shareholder value. While COVID-19 gave platforms a chance to become even more central to daily life, this pandemic also presents a window of opportunity to rethink the way platforms operate and the system they operate within. That window is closing quickly, but it’s not too late.