Rogers Communications’ recently proposed $26 billion acquisition of Shaw Communications — a deal that would merge two of Canada’s largest telecom conglomerates (second and fourth, respectively) — has set off a round of alarms. If approved, the merger could significantly reduce competition in mobile wireless markets in cities and provinces across the country, and drive up concentration in the national internet access market, as well as in the cable television distribution market. It would also blow a hole through the criteria used by Canada’s competition and communications regulators to assess these kinds of landmark transactions.

Beyond competition issues, there are myriad less-discussed factors looming with wide-ranging implications from the application of fifth-generation cellular technology — 5G — and the way it’s used to sell the smart city, to the telecom industry’s under-discussed role in data collection and advertising, to the clear need to shift the entire model of internet access to something different and truly equity-driven. It’s time for the public to take power back from the companies building the communications environment of the twenty-first century, and it’s time for all levels of government to end their support for the market failures that their policies and regulatory bodies enable. This means blocking the deal, and embracing new approaches that redefine how communications, internet and media markets in Canada are structured and how they operate.

The End of the Line for Canada’s “Maverick” Mobile Wireless Operator Policy

Since 2008, Conservative and Liberal governments alike have used spectrum auctions, regulated wholesale access requirements and taken other measures to help foster the development of a fourth mobile wireless competitor in all regions across the country in order to compete with the “big three” national carriers — Bell, Rogers and Telus. That policy has made solid progress. In Quebec, Montreal-based Vidéotron has carved out a market share of close to 20 percent, to the benefit of its customers, who have seen a drop in mobile wireless pricing, more generous data allowances and an increase in mobile wireless adoption levels. In the Maritime provinces (and Timmins, Ontario), Halifax-headquartered Eastlink accounts for about 10 percent of the wireless market, while in Alberta, British Columbia and Ontario, Shaw has been investing in building out its network and attracting subscribers. It has just over 8 percent market share.

One big-ticket item in the proposed Rogers-Shaw transaction will be the elimination of Shaw-owned Freedom Mobile, the fourth mobile wireless network operator in three provinces that account for more than two-thirds of the Canadian population: Ontario, British Columbia and Alberta. Over the past decade, Freedom has not only garnered subscribers in these provinces by offering more affordable wireless plans that feature more generous data allowances and no overage fees, but crucially, in recent years, it has forced the big three to respond by lowering prices and offering unlimited options.

Canada’s incumbent mobile operators — Rogers, Bell and Telus — have taken these price declines as evidence of a job well done. They also point to blistering fast download speeds that put the big three Canadian carriers at the top of the international comparative rankings on this measure.

It’s time for the public to take power back from the companies building the communications environment of the twenty-first century, and it’s time for all levels of government to end their support for the market failures that their policies and regulatory bodies enable.

However, it is still too early to declare a victory. This is because, despite important improvements, prices in Canada have fallen and data allowances have increased at rates far slower than in other countries. In addition, while the claim about blistering fast download speeds is true, when we look at the rankings for upload speeds, network availability and the quality of the networks for video, gaming and voice, Bell, Rogers and Telus slip down the ranks, with scores ranging from fair to very good, but never at the top. In other words, Canada is still a laggard, rather than a leader, on this front.

With Shaw out of the picture, these gains attributable to competitive pressure from Freedom will be reversed. The pledge that Rogers has made to maintain prices for Freedom customers as part of the deal is meaningless, since the brand will quickly be retired and customers will effectively be forced off their existing plans by evolving technology and the changing nature of demand. Bell made a similar promise when it absorbed Manitoba Telecom Services (MTS) in 2017; today Manitoba’s mobile services — once the envy of the rest of the country — have lost their edge.

Back in 2017, the Competition Bureau’s commissioners ignored their own staff’s advice to reject the Bell-MTS transaction. Manitobans are now paying the price. The Competition Bureau should not repeat its earlier mistake this time around. Approving the Rogers-Shaw deal would overturn a dozen years of progressive policy under two governments. Moreover, given that this is one of the biggest merger-and-acquisition deals in Canadian history, doing so would reveal the Competition Bureau to be an “emperor with no clothes,” and it would be open season for consolidation across the economy.

Approving the deal would also be bad news for Canadians insofar that adoption levels for mobile wireless services in Canada still languish at the bottom of the ranks among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (31 out of 36 countries). In addition, while “maverick” operators such as Shaw have brought about more generous mobile data allowances — to which Bell, Rogers and Telus have been forced to respond — mobile data usage in Canada is still half of the OECD average (5.8 GB per month per subscriber) and about one-third of what it is in the United States (9.2 GB). In other words, this is no time to abandon policies that have begun to deliver modest success.

Of course, Rogers and Shaw are touting the deal on the grounds that they will invest vast sums in 5G networks and bring broadband links to rural and Indigenous communities. However, it really isn’t clear whether the sums being touted represent new money over and above what they had already planned before the merger was announced, which should give serious cause for concern. In any case, how can Rogers and Shaw’s pledged commitments be tracked and verified after the deal goes through?

In addition, while Rogers and Shaw anticipate deploying 5G and other wireless networks to meet their pledges, most communities want fibre. Moreover, we should be concerned that Rogers and Shaw are introducing themselves as solutions to problems that they have both helped to create over decades.

The Myth of the Need for Metered Internet Usage

It’s often asserted that Rogers and Shaw aren’t direct competitors in the cable and internet access market and so their merger will have few, if any, effects. This assumption is incorrect. These two companies did, essentially, carve up the market into “Cable Monopoly East” (Rogers) and “Cable Monopoly West” (Shaw) 25 years ago. That regulators said nothing at the time, or since, is a testament to how compliant they have been in letting these firms set the terms of the landscape. While the companies did not compete with one another head-to-head, Shaw’s earlier embrace of newer cable network and set-top box technology revealed it to be the more innovative of the two firms. Telus was forced to respond in kind, which led it to roll out Internet Protocol television and fibre-to-the-home in Western Canada five years earlier than Bell did in Ontario and Quebec.

Moreover, Shaw decided not to enforce data limits on internet subscribers in Western Canada, while Rogers, Bell, Telus, Vidéotron, Eastlink and Cogeco did enforce limits in their markets. This decision showed that the use of data caps to limit internet use for what they are: an artificial construct. The idea that people can somehow be “using too much internet” is a myth, barring a few outliers of heavy or abusive users. Shaw’s decision, in other words, revealed that data limits on our internet connections are not about the technical need to manage limited capacity — as the companies often claim — but rather a marketing tool to sell differently priced internet tiers to different people based on their ability to pay, rather than on their genuine needs.

Bottom line: If this deal goes through, Shaw’s subscribers will have to get used to counting their downloads against a meter. This model relies on general confusion about how technology works and is precisely the kind of model we need to debunk and destroy, not entrench and expand.

Culture Creators Will Have One Less Door to Knock On

This proposed transaction could also have significant implications on television and film production and independent television service providers in Canada. Those affected would include cutting-edge entities such as OutTV in Vancouver and the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN). Why? Because Canada already has exceptionally high levels of vertical integration between telecom carriers and television by historical and international standards. As things stand, Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Québecor — the “big four” — own CTV, CityTV, Global and TVA, respectively, as well as over 100 other cable channels such as the Discovery Channel, Disney, Sportsnet, HBO and Canal Indigo. Accordingly, these carriers have both the incentive and the ability to act as gatekeepers. This reality of a media system so tightly beholden to just four communications conglomerates also hikes the pressure on the constantly beleaguered public Canadian Broadcasting Corporation to offset the concentration of power in the commercial media sector.

In 2010, recognizing these problems, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) created a vertical integration code that required the big four vertically integrated companies to deal with television programming services on commercially fair terms. That code, however, has been seen as a weak reed since its inception, resulting in independent television services such as OutTV, APTN, Blue Ant and other members of the Independent Broadcasting Group being disadvantaged by an extremely limited set of options to access their audiences. At present, they have only four doors to knock on at the national level to seek distribution deals. If the Rogers-Shaw deal goes through, that number of doors drops to three, and from three to two in the English-language regions of Canada. If these broadcasters can’t strike a deal with Bell or Rogers, they’ll be out of luck, or get tied up in protracted regulatory disputes for years in a fast-shifting landscape as new services (including Netflix, Amazon, YouTube Premium and Apple) move ever deeper into Canada. They will also have more incentives, in fact, to turn to Apple, Amazon and Google for distribution deals, thereby tightening the cultural industries’ dependence on the global internet platforms and, consequently, working at cross-purposes with principles of national sovereignty.

Municipal Internet Utilities and Community-Owned Networks

There are many other models that enable internet access for everyone and it’s time to move more of these options into the mainstream rather than maintain the status quo.

After decades going unserved, communities are increasingly taking matters into their own hands. Some of these alternative options include municipalities and communities setting up their own networks, as either public utilities or community-owned and -run infrastructure. These types of networks can co-exist in a market mix with a range of smaller internet service providers (ISPs), such as TekSavvy and EBOX, as well as First Nations, Métis and Inuit-led initiatives and members of CanWISP (the Canadian Association of Wireless Internet Service Providers). Increasingly, independent groups across Canada are working together to build their own broadband networks (see here for a helpful account of some such efforts). While these efforts are increasing, they face a common challenge: big telecom operators who refuse to allow them to interconnect with their networks, despite a wholesale regulatory mandate to do so. The CRTC appears to be unwilling to enforce its own rules on this front.

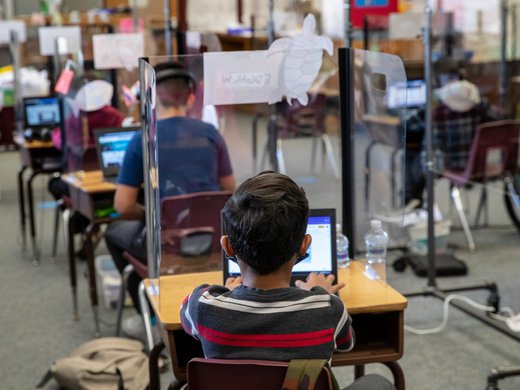

There is also an interesting under-discussed tension within cities in this moment, in terms of their responsibility to address the digital divide. Due to the pandemic, some cities are exploring new models, including the creation of more municipal ISPs that treat the internet as a public utility. After years of widespread business dealings with the telecoms, there is an undiscussed fear among city leadership of what it might mean to move into the telecoms’ turf. People are waking up to the opportunity to get the CRTC to enforce rules that are already on the books to support these alternative models. This opportunity includes proposals for new rules that would grant easier access to “passive infrastructure” (for example, streets, sewers, lamp posts and so on). This all ties neatly into the places where these policies become real to the people using them to build alternatives — the towns and cities and communities that house the physical infrastructures upon which communications networks and the internet run.

Smart Cities, Telecommunications Infrastructure and the IoT Inevitability Narrative

The 5G hustle is real, and it’s heavily tied to smart cities. For years, cities have been courted by carriers and hardware and software providers that promise urban utopias and intensive economic development all built on a network of smart devices and infrastructure connected by blazing internet speeds. These smart city fever dreams are political catnip, offering politicians that have been lax in getting municipal data governance under control an untested techno-optimistic approach to the climate crisis through sensors and data collection. It’s still easier to find enthusiasm for this story, no matter how old it is, than to muster the political fortitude necessary to invest in public transit, social housing and other system-level infrastructure. In short, the argument that 5G is necessary, and will be adopted sooner if this deal is allowed, has a large set of vested interests that extend well beyond those of Rogers and Shaw. With smart cities and the Internet of Things (IoT) come a slew of related governance issues, and some cities are better prepared than others to manage them. But these aren’t the only data issues related to this deal.

Online Ads and the Dirty Web (It’s Not Just Big Tech)

Some telecom operators are investing in data analytics as they build out their own proprietary ad exchanges. While the digital duopoly of Google and Facebook dominate online advertising, they are not alone. Indeed, AT&T, Verizon and Bell Canada, for example, have opened a new vector of vertical integration into the “big data” economy through a series of acquisitions of digital advertising and data analytics firms that they are using to build their own rival online advertising exchanges. To this end, for example, AT&T acquired AppNexus in 2019 (renamed Xandr), Verizon bought Yahoo in 2018 (now part of Oath), and Bell acquired the data analytics firm Environics in December 2020.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada investigated Bell’s Relevant Advertising Program (RAP) in 2015. Its findings provide a glimpse of what these efforts might look like and should put to rest any belief that the telecoms/internet access operators are more innocent than the tech giants when it comes to data and privacy protection: “Bell is able to track every website its customers visit, every app they use — and, in the future, every TV show they watch and every call they make — using Bell’s network, whether at home or abroad. … the combination of this information with the extensive account/demographic information (e.g., age range, gender, average revenue per user, preferred language and postal code) used by Bell for the RAP will result in highly detailed and rich multi-dimensional profiles that, in our view, individuals are likely to consider quite sensitive.”

Adding up all these issues tallies to one result: the current model of internet access is beyond reform.

Bell subsequently withdrew the RAP initiative, but the thrust of the program has been resurrected under the collective control of most of the major communications and media groups in Canada, all under the not-so-watchful eye of the CRTC, and with little to no public participation. With data combined from 18.2 million Canadians integrated across Rogers’ and Shaw’s multiple platforms — internet access, mobile wireless, cable TV, mobile and desktop browsers — this is also a “big data” deal and raises substantial questions about the link between that data and market power as well as about privacy and data protection. As such, this is an excellent opportunity for the Competition Bureau to put its recent words about the intersection between big data and its own analysis of mergers and market power into action.

Of course, AT&T, Bell, Verizon, Rogers and Shaw and other entities that are building up these massive and valuable data troves claim that doing so will help to provide a competitive alternative to Google and Facebook, but their approaches are better seen as an ill-advised attempt to emulate their strategies. A better strategy would be to rein in the “surveillance capitalism” machine by adopting and applying strong data and privacy protection rules across every layer of the internet stack.

Thus far, the efforts for telecoms and media giants to replicate the online advertising business models of Google and Facebook have hardly put a dent in the digital duopoly’s dominance. Instead, they have arguably made a bad situation worse. Indeed, nobody, except perhaps Google and Facebook, is satisfied with the status quo: sky-high levels of online advertising concentration; an inscrutable “dirty web” founded on rival proprietary technical standards; unbridled data harvesting; and fraudulent representations of audience reach and composition.

The US Federal Trade Commission acknowledged such problems as early as 2011 but did nothing about them, although they are once again under review, as Google and Facebook currently face probing questions from the US House Judiciary Committee’s Digital Market Investigation and the landmark lawsuits that have flowed out of that proceeding. The UK Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has also condemned the industry for trading on key words and sensitive personal identifiers related to politics, religion, ethnic groups, mental health and physical health, among others, as well as device identifications, location data, cookie identifications, fraudulent representations and dirty data. According to the ICO, the entire set-up also does not comply with the European Union’s General Data Protection Rules.

Given the far-reaching implications of these trends, there are several prime targets for a new era of internet regulation: structural separation and/or firewalls between different activities in the vertically integrated online advertising stack, as well as rules to govern network interoperability, data portability, and personal privacy and data protection.

Rejecting the Merger, Rejecting the Status Quo

Adding up all these issues tallies to one result: the current model of internet access is beyond reform. In this moment in time and in this moment of crisis, when there are so many others doing differently and doing better, it is these businesses and communities that deserve support for innovation in the face of a truly reprehensible policy-enabled competitive landscape. With this deal, and with others like it globally, advocates for public technology and believers in the importance of closing digital divides should line up in opposition. Consolidated power in these infrastructure systems serves no one but the companies. Democratic governance — by way of policy and regulation — should be doing everything it possibly can to support and expand different models for access and governance of our infrastructures. Data governance has garnered a lot of attention in years past, and digital infrastructure governance requires just as much attention. We must shift to models that prioritize the public good and ensure more public involvement in governance well into the future. In terms of a taking an important step in that direction, regulators and policy makers who hope to serve the public interest should do what they can to oppose this merger.