In the late 1990s, when I was a (non-partisan) economist for the Library of Parliament, a member asked me to write a report on the emerging digital economy. I never finished it — the dot-com bust tempered the parliamentarian’s interest in the topic — but this work taught me a valuable lesson about the importance of looking beyond the hype to see things for what they are.

And what hype there was. It was a time when a company’s value could explode just with the addition of a website. Many believed we had created an unprecedented “New Economy.”

My moment of understanding came in an interview with a West Coast entrepreneur, who had set up an e-commerce website (a quaint phrase from a more innocent era). While they were telling me about their business, I suddenly realized they were basically just describing a souped-up version of catalogue shopping. That’s it.

This isn’t to say the internet and Web 2.0 (social media version) didn’t introduce novel innovations or policy complications. But for all the new e-commerce buzzwords — B2B, B2C, C2C — it was still just selling products to people. Breaking through the jargon demystified for me this supposedly new economy. It became much easier to understand.

It feels like we’re in a similar moment with the so-called platform companies. Much as with the hype surrounding the dot-com boom, it can sometimes be hard to get a handle on what a “platform” actually is.

Indeed, platform is one of those words that tends to mean whatever the speaker wants it to mean. It’s what Microsoft researcher and communications scholar Tarleton Gillespie calls, in an essential 2010 article, a “structural metaphor” underwritten by “terms and ideas that are specific enough to mean something, and vague enough to work across multiple venues for multiple audiences.” For example, as Gillespie points out, it can refer to computational or online infrastructures that support different applications or actors, a raised-level surface, a grounds for action, or a political program.

Gillespie highlights how, ideologically, social media companies use the term to “present themselves strategically” to end-users, advertisers and professional content producers, “while resolving or at least eliding the contradictions between them.” For example, in terms of user-generated content, platform functions as a wink-and-a-nod support for free expression. When talking to retailers, the platform “is a distinctly commercial opportunity … a ‘platform’ from which to sell, not just to speak.”

Even Gillespie’s approach is limited by his focus on social media and content companies. eBay may not be a social media company, but we also tend to think of it as a platform.

In the end, when it comes to public policy, platform doesn’t really get us very far. It obscures more than it reveals.

Better, then, to focus on how companies that identify themselves as platforms actually operate: that is, on what business model they use, rather than the ideology and jargon they deploy. Focusing on the actual rather than the rhetorical helps clarify the exact policy challenges posed by these companies. What’s more, cutting through “platform” fuzziness helps us identify potential policy options that may be obscured by this conceptual fog.

What do we mean when we talk about platforms’ business models? There are any number of different ways to answer this question, but let’s focus on two fundamental characteristics of the model, and three characteristics that we incorrectly assume are natural and unalterable. As we’ll see, it’s this assumed unalterableness that often ends up handcuffing well-meaning policy makers.

Platforms and Data

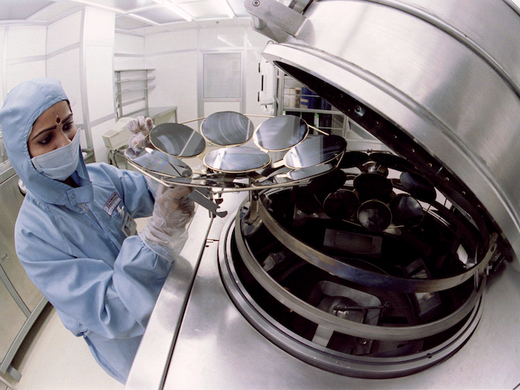

First up, of course, is data. As Nick Srnicek notes in his still-unequalled 2016 book Platform Capitalism, the platform business model is designed to collect data. Importantly, this business model is not just limited to online companies or personal data. It’s also becoming a standard throughout the economy. Every company can potentially reorient itself to maximize data capture. Srnicek discusses, for example, “industrial platforms”: manufacturing companies such as Siemens, that have reorganized production processes to maximize data capture, both during production and once their products are out in the wild.

Unhelpfully, as the Gillespie article suggests, platform has effectively become synonymous with social media, or, at a stretch, search engines. However, the problems of a data- and intangibles-based economy are more pervasive than those posed by social media companies alone. In particular, such an economy creates a winner-takes-most dynamic that ends up benefiting a small group at the expense of most of us, and exacerbates problems of income inequality and economic development. Treating platforms as equivalent to social media makes it that much harder to persuade policy makers to consider the challenges of the data economy.

Two-Sidedness

Second, platforms operate as two-sided markets, meaning that they work as intermediaries that connect two or more sides in a transaction. This position provides them with a form of structural power to set the rules governing how users interact. It also allows them to see both sides of the transactions occurring in their space. This limited omniscience potentially provides them with a leg up to compete against their users. Amazon, for instance, can see pretty much all the data related to the third-party sellers that depend on its Amazon Web Services platform, placing the company in a privileged position to conceive and market its Amazon Basics line of goods.

As the current US Federal Trade Commission chair, Lina Khan, wrote in a 2017 Yale Law Journal article, “Whereas brick-and-mortar stores are generally only able to collect information on actual sales, Amazon tracks what shoppers are searching for but cannot find, as well as which products they repeatedly return to, what they keep in their shopping basket, and what their mouse hovers over on the screen.” As a result, “Amazon increases sales while shedding risk. It is third-party sellers who bear the initial costs and uncertainties when introducing new products.” Concludes Khan: “Amazon is exploiting the fact that some of its customers are also its rivals,” with “its control over data” that heightens the “anticompetitive potential” of its platform dominance and its status as a retailer and third-party marketplace.

Important aspects of this two-sidedness, however, are not unique to online companies. Banks, for example, are in the business of indirectly connecting those with money with those who need money. At the very heart of a financialized economy, they are intermediaries that, like platforms, have privileged access to commercially sensitive data that is almost always subject to protections.

Bottom line: While platforms may be two-sided markets, the unfettered way in which they operate is a policy choice, which we’ve been quick to address in other, non-tech areas.

Treating these companies as if they are equivalent to the global internet makes it almost impossible for countries to regulate them effectively, to deal with legitimate domestic concerns in the most straightforward way possible.

Taken for Granted: Assuming the Global

Data capture and two-sidedness are inescapable aspects of the platform business model. But beyond these are other features that are much more contingent. Although we might take them for granted, these are aspects that are accidents of history, not immutable givens. Understanding this difference is essential for a full consideration of how to regulate these companies in the public interest.

The most obvious but invisible embedded assumption in the platform business model is that they must be global, largely undifferentiated companies. Calls by democratic countries to regulate platforms (usually referring to social media companies) to address real and pernicious problems such as online hate speech and to require data localization are regularly met with howls of “Balkanization!” and “Splinternet!”

Take a step back, though, from this false equivalence of individual companies with the internet itself. From a distance, it becomes clear how odd and unusual this view — that these companies should operate under a global remit — actually is.

Even finance, arguably the most global industry, is comprised of interconnected national financial systems — and with good reason. For one thing, different countries have different appetites for risk in their financial systems. These barriers also help to ensure that when these risky bets go south, as happened in the United States in the 2008 global financial crisis, everyone else isn’t dragged down with them.

Treating these companies as if they are equivalent to the global internet makes it almost impossible for countries to regulate them effectively, to deal with legitimate domestic concerns in the most straightforward way possible: domestic regulation by democratic governments.

As usual, social media platforms get all the attention on this issue. However, the imposition of a platform’s standards on a global audience is a more general problem of undifferentiated platform models, including payment intermediaries, and even agricultural companies, whose terms of service regarding data collection by their tractors and equipment shapes the lives of farmers around the world.

In the social media space, for example, taking this “globalness” for granted leads to schemes by well-meaning human-rights advocates that depend on milquetoast measures such as local or international advisory boards that issue non-binding recommendations and fail to challenge companies’ structural power.

Taking these companies’ undifferentiated globalness as a given rather than an aberration redirects our attention away from potentially more equitable ways of addressing the challenges raised by these companies. We could take the need for democratic accountability more seriously. We could also recognize that different societies may have different risk tolerances, as economist Dani Rodrik puts it, and that taking this hyperglobalness for granted effectively imposes the same standards on everyone.

This realization could serve as a foundation to shift the policy debate toward creating minimum international interoperability standards that respect domestic democratic differences and restrict the ability of globe-spanning for-profit companies to regulate solely according to their own interests.

No Employees, No Problems

Another characteristic is the tendency for companies such as Uber to claim that the workers who create value for the company, who perform tasks under its banner and give it a percentage of everything they earn while working collecting fares they obtained through its app, are not employees, but freelancers or contractors, or users.

The minimization of the employer-worker relationship is part of the platform model as it’s been allowed to develop. Think of a company such as YouTube. Do those who post user-generated content to the site work for that company? In the platform world, content creators tailor their product or content to the exigencies of a company that then decides, through its algorithmic regulation regime (which it can change at any time, for any reason), how and to whom it will promote that product or content, while taking a cut of the advertising it places in the creators’ programs.

Brooke Erin Duffy, an associate professor of communication at Cornell University, argues that those who depend on these companies for their livelihood are subject to “algorithmic precarity,” operating at the mercy of algorithms that steer “workers through overlapping systems that direct, evaluate and discipline them.” That sounds like a worker-employer relationship to me.

The denial of an employer-employee relationship is a form of “platform exceptionalism” — the idea that platforms are sui generis.

Claiming such exceptionalism certainly has its perks. No acknowledged employees means you don’t have to pay benefits. You also avoid being regulated as if you were part of the industry in which you are, for all intents and purposes, operating. The legislative and regulatory battles to regulate Uber as a taxi service, in Canada and elsewhere, and the Canadian government’s attempt to bring streaming platforms under the Broadcasting Act are fronts in the same battle, using the same techniques. The goal: to minimize regulation as much as possible.

If you believe that platforms should serve as many people as possible, as quickly as possible, at as low a cost as possible, then sure, good content moderation at scale is impossible.

Automated Regulation

Probably the most taken-for-granted aspect of these companies involves the seemingly mysterious algorithm. An algorithm is merely a set of instructions repeated over and over: it’s basically automated bureaucracy. Platforms have become almost synonymous with such automated bureaucracy. At this point, we expect platforms, be they social media companies or smart cities, to use these tools.

But whether it’s Twitter or a social services agency, the assumptions underlying the taken-for-grantedness of automated regulation are the same. First, that the goal of a platform should be to cover as many people and as much activity in as undifferentiated a manner as possible. Second, that decisions (whether on welfare eligibility or permitting a tweet to be posted) should be made immediately. Third, that because it’s costly and inefficient to employ human moderators or human oversight, it shouldn’t (or can’t) be done. This last point is significant because it highlights automated regulation’s cost-minimizing role, always attractive to businesses and governments alike.

Think about the wise-sounding but empty slogan, “Content moderation at scale (that is, over lots and lots of people) is impossible to do well.”

If you believe that platforms should serve as many people as possible, as quickly as possible, at as low a cost as possible, then sure, good content moderation at scale is impossible. But there’s no reason to accept any of these assumptions. Scale could be restricted to a manageable size in ways that prevent bad outcomes. Most activities do not require lightspeed decision making, especially if the decision could have potentially life-altering consequences. Governments and businesses could increase the amount of money they spend on actual human oversight. And if you can’t afford to provide a humane, non-toxic experience, maybe you shouldn’t be in business at all.

New Eyes

My 1990s-era dot-com epiphany and this discussion of platforms share a common focus on what companies in the digital economy actually do. Now, as then, it’s easy to get swept up in the hype, the feeling that we’re facing something so unprecedented that we have to take it as given. That wasn’t the case in the 1990s: the subsequent dot-com bust showed that investors finally realized that things hadn’t changed that much.

Nor is it the case today. Much of what seems natural or inevitable about platforms’ dominance is the consequence of conscious and unconscious policy decisions, and of ideas we just take for granted. And a lot of that is due to our too-often-uncritical use of the word platform.

In contrast, focusing on the platform model, rather than “the platform,” opens up a world of possibility. But first we have to see these companies as they really are.