The decision by the U.S. Supreme Court not to hear Argentina’s appeal appropriately focuses attention on the pari passu clause in the bonds under litigation promising equal payment. As an earlier post suggests, this outcome is likely to lead to changes in the market for sovereign debt, including the contractual terms of new debt issues and where it is issued, as Torrens Hume pointed out in his comment on that post. Prior to the 1990s, most sovereign lending was intermediated through large banks in New York, London, Frankfurt and Tokyo. That changed after the debt crisis of the 1980s, however, as the market for sovereign bonds expanded.

Why?

Well, bonded debt was deemed de minimus in the debt restructurings of the 1980s and escaped unscathed. Bank debt, in contrast, was rolled over, rescheduled and eventually restructured. Now, if you were a banker in the 1990s you would be reluctant to repeat that experience. But investors were quite prepared to load up on sovereign bonds given the favourable treatment accorded bonded debt. As a result, large international banks reinvented themselves, working with their former borrowers to issue bonds and harvesting the underwriting fees without taking sovereign risks on their balance sheets. As one senior New York banker said to me in the wake of the Asian financial crisis: “we’re all investment banks now.”

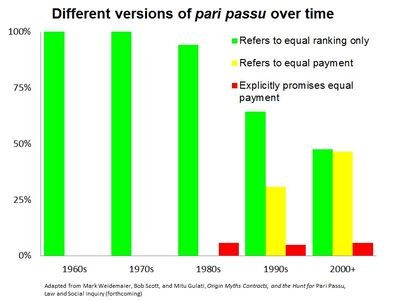

That wasn’t the only innovation in sovereign lending. As illustrated in the chart above, pari passu clauses — long used as boiler plate language in international sovereign bonds — also evolved. From provisions calling for equal ranking, or equal preference to avoid borrowers discriminating between creditors, in the 1990s, pari passu clauses began to refer to equal payments, with a smattering of issues explicitly promising equal payment. By the 2000s, bond issues with references to equal payment were running neck and neck with issues referring solely to equal ranking. The reason for this evolution is clear: in the debt restructurings of the 1990s bonds were no longer considered de minimus as the net for debt subject to re-contracting was spread wider and wider.

As the case of Argentina highlights, the meaning and enforcement of those clauses is problematic. Moreover, it can be argued that the evolution of “bonding technology” underscores the limitations of purely contractual approach to sovereign debt restructuring. Market practice is dynamic; for every contract innovation that helps facilitate timely, orderly restructurings there will be a reaction on the part of investors to reduce the likelihood of renegotiation, and vice versa.

All of this introduces one more source of uncertainty in the miasma that obscures global prospects in the New Age of Uncertainty.