In our introduction to CIGI’s The World Votes, 2024 series last February, we wrote: “One year from now, people could inhabit very different political worlds than the ones that currently exist.” We were right about that! But what role did digital tech play? Let’s consider by revisiting what we set out to learn in this comment series, and what we did not foresee.

Our first aim was to provide “clearer-eyed evaluations of the use and misuse of digital technologies in election campaigns.” We sought to avoid overly simplistic claims that social media platforms are entirely responsible for unwanted election results or democratic declines.

One key observation is that concerns about digital campaigning should not be limited to foreign disinformation and domestic outrage campaigns. While foreign interference and online toxicity remain important, the Indonesian election showed the importance of influencers and manipulated positivity. Ross Tapsell described that election as “a fake campaign without fake news. AI was used to sanitize discourse rather than muddy it.”

Debates about digital technologies also revolved around whether generative AI would be the killer app for elections in 2024. Wired tracked the extensive experimentation with AI in campaigns, from resurrecting dead politicians to deepfakes to bots. However, most evaluations suggest that AI empowered existing anti-democratic tactics — including sexualized harassment of candidates — rather than creating completely new ones. Our co-authored report on this issue concluded that generative AI would become pervasive, but not necessarily persuasive. Nevertheless, AI has changed the game: AI’s role in flooding or faking content — and suspicions of this happening — is now baked into the information environment.

Problematic digital content may be prevalent, but it does not necessarily win elections. A more profound factor appears to have been a global anti-incumbent vibe. While Donald Trump won in the United States and far-right parties made gains throughout Europe, the UK Conservative Party lost and the conservative party in Japan experienced its worst result since 2009. The winds of change did not have one political direction, except against whoever was currently in power. Even when a party remained in power, like the Bharatiya Janata Party in India, there was often an “unexpected setback,” reminding us that disinformation campaigns had limits “in the face of harder material realities,” as Sanjay Ruparelia put it. This doesn’t mean that digital campaigning is irrelevant. But it suggests that massive ad spends, celebrity endorsements, AI-powered tricks and other campaign flourishes are all secondary to people’s social identities, economic circumstances and felt experiences.

Our second aim was to examine “how new regulatory approaches shape the online environment during elections.” These approaches included the European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) that came into force in February 2024, the United Kingdom’s Online Safety Bill and ongoing efforts by platforms such as Meta’s Oversight Board.

The DSA generated detailed guidelines for platforms and has resulted in several ongoing investigations. Given potential Russian foreign interference in the first round of the Romanian presidential election in November 2024, the European Commission has, for example, ordered TikTok “to freeze and preserve data related to actual or foreseeable systemic risks its service could pose on electoral processes and civic discourse in the EU.”

Regardless of whether legislation had been enacted or not, our authors reinforced the importance of transparency and the difficulty of ensuring its efficacy. In the case of the European Union, Heidi Tworek stated that transparency has not yet occurred in quite the way envisaged. In the United Kingdom, Kate Dommett argued, the continued lack of transparency for parties’ use of social media means that “our ability to identify and hold campaigners to account for problematic content is severely curtailed, raising questions about our ability to uphold and ensure electoral integrity.”

A more fundamental question is how governments’ regulatory approaches may apply in future elections. Even platform access may differ depending on owners’ willingness to comply with local laws. In Brazil, the standoff between X and the Supreme Court eventually ended with X adhering to existing laws and the Supreme Court lifting its month-long ban on the platform in October 2024. It is unclear how such disputes might unfold after Trump re-enters the White House in January 2025, given that he may throw US diplomatic and economic support behind tech barons like Elon Musk.

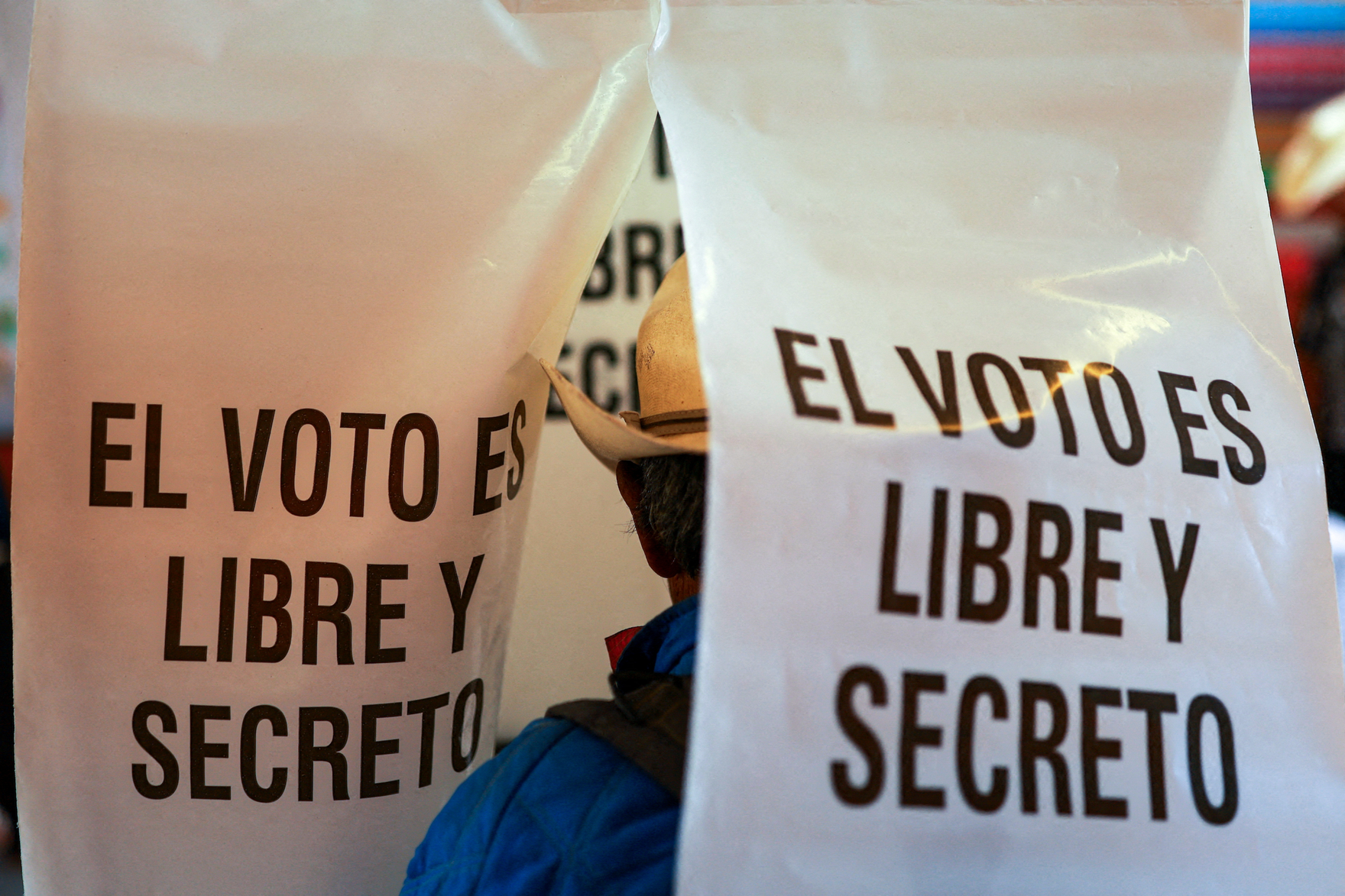

Beyond the digital, 2024 reminded us that regulating electoral communication has always been complex and that political leaders’ behaviour can drive disinformation. Violations by current leaders were a frequent issue, though sometimes not connected to new technologies. For instance, Pamela San Martín explained the Oversight Board’s recommendations for platform behaviour in elections, but also observed that then Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador routinely violated election regulations during daily press conferences. Similarly, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi violated the Model Code of Conduct put forward by the Election Commission of India in 2019. In Ghana, competing parties made false statements and denounced their opponents’ “fake news.” As John Osae-Kwapong pointed out, “There seems to be no self-restraint among some political actors when it comes to misusing technology to gain political advantage.” Clearly, while platforms may enable problematic campaigning, political elites remain the principal protagonists.

Aside from specific bills and stand-offs, the Taiwanese election offered renewed evidence for the importance of strong electoral institutions, societal cohesion, civic education and state investment in civil society monitoring. Chung-min Tsai and Yves Tiberghien concluded that “although Taiwan’s democracy is operating in a highly disruptive environment, its institutions and voters have shown tremendous resilience.”

Third, we sought to contextualize the US election as important, but not an event that should “eclipse attention on the rest of the world.”

In some ways, the US election provides broader lessons. As Samuel Woolley suggested, social media companies might better avoid problems if they “invest in societal solutions that prioritize people’s knowledge and experience of the issue, and of their own communities.” Meanwhile, Dean Jackson diagnosed factors that increase risks of social media-facilitated violence following US elections, even if that scenario did not play out in 2024.

The US election may prove more pivotal for the future of platforms in ways we did not anticipate, including broad changes to content moderation.

The starkest example of brash partisanship came from Musk, who contributed his brand, money and platform to the Trump campaign. Musk’s efforts included a legally challenged lottery, promoted on X, to boost voter turnout for Trump. Following the election, both Meta and Amazon offered to contribute US$1 million to Trump’s inauguration fund. Although Meta’s platforms, such as Threads and Instagram, de-emphasized political content prior to the election, on January 7, 2025, Mark Zuckerberg announced sweeping changes to Meta’s content moderation policies. Changes include cutting its fact-checking program and dramatically altering the “hateful conduct” community standard. For example, Meta now allows many types of language previously removed as harmful, such as “allegations of mental illness or abnormality when based on gender or sexual orientation.”

The US election result spurred these changes, yet they have global import. As Tom Divon and Jonathan Corpus Ong observed, Meta’s new approach “prioritizes a narrow vision of free speech rooted in American exceptionalism, overlooking the global impact of these policies on marginalized communities and fragile information ecosystems.”

The United States is thus arguably more central to tech and political developments globally at the end of 2024 than at the beginning. At the same time, there are definite risks of Trump and Musk dominating attention while other platforms and countries are neglected. One former Facebook employee fears that the consequences of Meta’s new policies will be far worse outside the United States, calling them “a precursor for genocide.”

Finally, what did we not predict or consider? While it’s obvious that online influencers are increasingly important, we did not anticipate how this trend might be gendered. For example, a Pew report found that nearly two-thirds of social media news influencers in the United States are male. The US election also highlighted the importance of podcast platforms, reminding us not to focus solely on social media.

We predicted platforms such as Meta and TikTok would face intense criticism for content moderation during the 2024 elections, as we saw in Cambodia in 2022 or in the United States in 2016. Intense debate and right-wing uproar over suppression of the “Hunter Biden laptop” story in 2020 was replaced by silence when Meta and X (after consulting Trump) decided to block links to hacked material from the Trump campaign in 2024. There certainly has been some criticism globally, such as alleged policy failures by YouTube and Meta in Indian elections. But with the exception of the focus on TikTok’s role in foreign interference in Romania’s recent election, major platforms have not faced systematic civil society and government recrimination for election-related decisions.

The election mega-year is over, but the elections will keep coming in 2025, from Canada to Cameroon to Australia. The political passions and socio-economic structures that drive voters will continue to evolve, and so will the digital technologies that mobilize, enflame, distract and reflect us.