As Russia’s war in Ukraine crosses its six-month mark, and the People’s Republic of China steadily ramps up its rhetoric and pressure following a visit to the Indo-Pacific by US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, countries such as Canada face important questions: How does one protect and promote a strained international rules-based order? And how do countries cope with threats posed by authoritarianism and dictatorships globally and avoid future conflict?

American democracy is facing the test of a generation. At the same time, it is reassuring to see that US institutions and citizens are having open and difficult conversations about the state of their democracy. This is in stark contrast to how dissent is treated in countries such as Russia and China — both of which are increasingly seeking to test the rules-based international order and clamp down on criticism of their respective governing regimes.

US foreign policy makers have apparently understood that if their country is to compete internationally, they must seek to strengthen the liberal international order and engage like-minded partners to build pressure and multilaterally raise the cost of belligerent behaviour. This push is a much-needed development, and one calculated to re-establish lost legitimacy in the wake of several missteps since the ill-advised invasion of Iraq in 2003. This American push incidentally provides Canada with a once-in-a-generation opportunity to be involved in jointly shaping foreign and defence policies during a period of sharp international transition.

What Challenges Does the International Order Face?

The liberal international order has realistically been under pressure for some time. Post–Cold War optimism that undemocratic countries would liberalize economically and politically, as global trade flourished, was misplaced. Instead, authoritarians have exploited perceived weaknesses in the international system to invade neighbours, co-opt international bodies to legitimize their own regimes and challenge democracies’ resolve to enforce rules.

Beyond Russia’s aggressive behaviour, the most striking example of the past three decades is China. The world’s most populous country is a crucial part of international supply chains and is deeply connected to (and, to some extent, reliant on) Western markets. Yet Chinese leadership has managed to sidestep pressures to politically liberalize. With the use of technology, Beijing now has unprecedented power to surveil, manipulate and control political discourse within China.

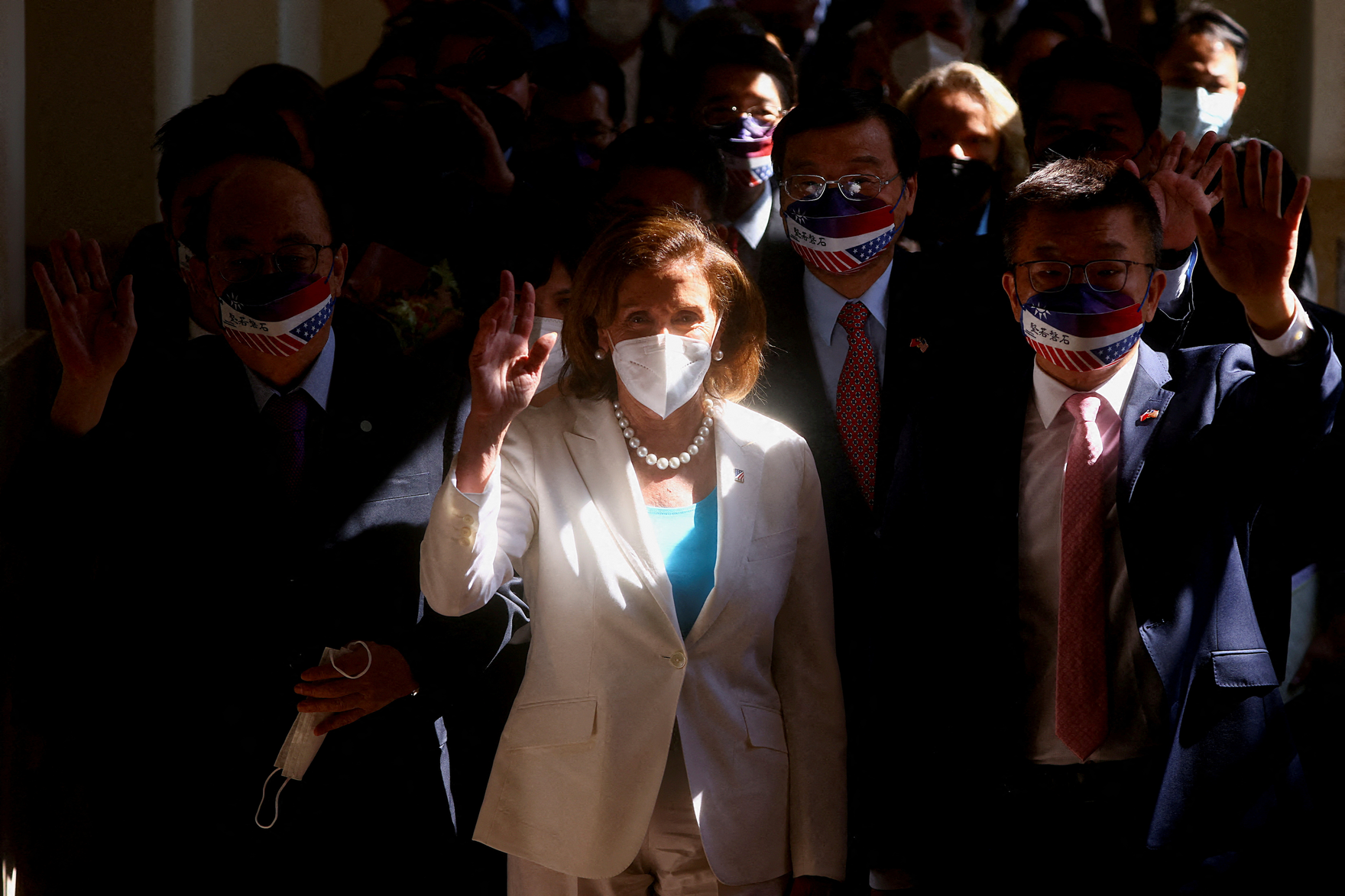

And while its economy is imperfect, the country has skillfully used its economic and political relationships to apply strategic pressure on trading partners and build relations with those (namely, Russia and Iran) who share skepticism about a Western-dominated liberal order. In engaging with China, it has become clear for some countries (including Canada) that bilateral relations can carry hidden caveats, and that Chinese leadership is not afraid to arbitrarily sanction or penalize states over issues the Chinese Communist Party deems important. China’s decision to pull out of talks on climate change with the United States in response to Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, for example, indicates it is willing to use critical global cooperation issues to make a point. The country has, furthermore, blatantly disregarded its own commitments in Hong Kong and repeatedly threatens military action in Taiwan — holding the lives of almost 24 million Taiwanese nationals in limbo in an effort to project strength.

Clearly, the US-led international order is struggling to dissuade states such as Russia and China from behaving poorly. This is likely because these countries believe the cost of flouting postwar international standards is one they can bear. But, as the West’s recent actions vis-à-vis Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine shows, international cooperation still has the capacity to punish poor behaviour — and cooperation with partners can have an impact.

Discouraging Bad Behaviour

There is evidence that like-minded countries are finally starting to acknowledge the challenges countries beyond Russia pose to the international system and that international cooperation is key to dissuading future conflict. For example, in late June 2022, heads of state and government of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) noted that China challenges NATO’s “interests, security, and values” and seeks to “undermine the rules-based international order.”

Authoritarian states will argue that such behaviour represents an effort at containment. China, in particular, arguably prefers bilateral engagements in which it can wield outsized influence. China therefore has a vested interest in discouraging or breaking down collaboration between democratic countries, even if it is defensive in nature. Hence, Beijing’s rhetoric regarding containment and unfair “bullying” of China has increased.

To exert influence in this emerging world order, middle powers such as Canada will need to work with other mid-sized, like-minded democracies (and the United States, when appropriate) when addressing challenges to the international order. Canada’s efforts to coordinate international support on a joint declaration on hostage diplomacy, for example, demonstrated how powerful such multilateral coordination can be; the motion undoubtedly put pressure on China after its arbitrary detention of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor.

What’s Next for Canada?

Rather than view the United States’ renewed attempt to build multilateral relationships and push back against countries such as China (which has spent years trying to manipulate international institutions, steal intellectual property, economically coerce weaker players, threaten human rights and politically indoctrinate youth) as problematic or divisive, Canada should instead view this development as a golden opportunity to once again play a leading role in shaping new international institutions while pushing back against authoritarianism. Engagement with other like-minded middle powers also serves to hedge potential risks of political shifts in US domestic and foreign policy.

The balance of power in the international system is undoubtedly shifting. And while the United States is far from perfect, its international or domestic missteps do not justify Russia’s or China’s attacks on the rules-based international order, democracy and freedom. Whatever the near-term outcome of political shifts in the United States, the reality is that Canada’s interests lie in supporting a US-guided global order, rather than a Russian- or Chinese-led one. In international relations, there are no perfect outcomes.