The question of cumulative environmental impact is one of the most practically pressing problems in litigation under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. Aboriginal peoples throughout Canada are faced with both the accumulating impact of intensive resource extraction projects and the increasing demands for new projects on their territories. Examples of this issue are easy to find: from the impacts of hydroelectric dams in the Nechako Valley of British Columbia, to mercury contamination in the Keewatin area of Treaty 3 in Ontario, to the overlapping impacts of dams, logging, mining, and oil and gas development in the Peace River Valley and Wood Buffalo Park areas of Treaty 8 in British Columbia and Alberta.

From a practical perspective, it is easy to understand how the environmental impacts of extractive developments overlap and accumulate. The construction of a coal mine, a sawmill and an oil well on a given territory obviously have overlapping long-term impacts on the surrounding environment. And yet, in legal terms, this rather common-sense problem has become one of the most tangled and vexing areas of section 35 litigation. This is, at least in part, because the issue of cumulative impact arises in two distinct areas of the case law and each addresses it (or fails to do so) in ways that tend to further complicate matters. The courts have tended to either view each individual project on its own terms (as in Saugeen First Nation) or to refuse to acknowledge cumulative effect as a barrier to development until it has effectively rendered the landscape unusable for the exercise of treaty rights (as in Mikisew Cree). This doctrinal quagmire has left Aboriginal peoples in the perverse position of seeing their rights extinguished and the environmental integrity of their lands eroded.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) may provide ways to change the current doctrine so that the courts can meaningfully address the problem of cumulative infringement. This essay will provide a brief outline of how this could be done.

The Issue of Cumulative Infringement in Section 35

The problem of cumulative infringement in section 35 litigation has come up in cases involving asserted and treaty rights. This has led to the development of distinct analytical approaches. First, in cases involving asserted rights, the court in Rio Tinto found that for the duty to consult and accommodate (DCA) to apply, claimants must show a direct causal relationship between the proposed government conduct or decision and the adverse impacts on Aboriginal rights. As they put it, “Past wrongs, including previous breaches of the duty to consult, do not suffice.”

This result made sense within the confines of the facts of that case. The question was whether an application for approval of the sale of excess power generated by a hydroelectric dam in 2007 could be challenged on the basis of the adverse impacts dating back to the construction of the dam in the 1950s. The argument put forward by the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council in Rio Tinto used the logic of the fruit of the poisoned tree (an evidentiary doctrine that holds that the Crown cannot benefit from past wrongs) to broaden the duty to consult. The court rejected this argument because they saw it as incompatible with the duty to consult framework established in Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests). In the court’s view, “An order compelling consultation is only appropriate where the proposed Crown conduct, immediate or prospective, may adversely impact on established or claimed rights.” It is not that the court did not see the cumulative infringement as a problem; rather, they simply saw it as one that was better suited to what they referred to as “other remedies.”

This argument has had significant impact on the doctrine of the duty to consult and has resulted in further complications. In Rio Tinto, there was no present harm, but in some subsequent cases, there has been a present harm; still, courts refuse to consider the cumulative impacts on the basis of the Rio Tinto analysis. A careful reading of Rio Tinto would confine its application to cases where there is no present harm and thus render it compatible with the analysis in West Moberly and Chippewas of the Thames, which consider cumulative impacts as being part of the context of a proposed project. The need to demonstrate the relationship between the adverse effect and the project unfairly places the onus on Aboriginal peoples to determine how the proposed project will impact their rights.

The courts have continually maintained that consultation is a “two-way street” and they have withheld relief in cases where they find that the Aboriginal party’s obligations were not met. Yet, the narrow focus of Rio Tinto prevents the courts from taking into account the fact that Aboriginal peoples are dealing with several ongoing consultation processes at any one time and that they live on the landscapes where the effects of these projects accumulate. Rio Tinto has effectively converted the “two-way street” from Haida into a double-bind. They are left with the unhappy dilemma of either expending all their resources engaging in consultation processes and litigating those that fail or simply standing back and watching the piecemeal erosion of their territories.

Meanwhile, the Crown can draw on its unlimited means to initiate an endless series of consultation processes. If this can still be plausibly characterized as a “two-way street,” it must be said that there is a significant disparity between the sides of the street that each partner travels on. The upshot of this is that Aboriginal peoples who want to make use of the Haida framework to prevent the Crown from running roughshod over their territories are stuck with the task of untangling the overlapping and interrelated harms of accumulating extraction so that they can clearly specify how a single project will cause a harm significant enough to constitute an infringement.

The second context where cumulative impacts arise is in cases involving treaty rights. In cases such as Mikisew Cree and Grassy Narrows, the courts have established that the cumulative impacts of Crown activities can be taken into account as having a bearing on the “meaningful right to hunt,” but they are counterbalanced by the effect of the “taking up” clauses found in many of the numbered treaties. The threshold for this balancing test is clearly set out by the court in Mikisew Cree:

“If the time comes that in the case of a particular Treaty 8 First Nation ‘no meaningful right to hunt’ remains over its traditional territories, the significance of the oral promise that ‘the same means of earning a livelihood would continue after the treaty as existed before it’ would clearly be in question, and a potential action for treaty infringement, including the demand for a Sparrow justification, would be a legitimate First Nation response.”

Consider the practical implications of this legal test. For Aboriginal peoples to use their treaty rights to legally challenge the Crown’s ability to use the “taking up” clause, they must prove that their traditional territory can no longer sustain the wildlife that they hunt. In other words, the “meaningful right to hunt” is only a cause of action once it is practically extinguished. The legal test here operates like a cross between a scale and a trapdoor: it is insensitive to changes in weight up to the point that it is triggered, and then whatever the claimant had sought to protect is swallowed up. While Aboriginal peoples can use the DCA framework to challenge an infringement without needing to hit this “meaningful exercise” threshold, the DCA primarily serves to guide the procedure of unilateral Crown infringement and so has limited utility as a meaningful shield for treaty rights.

This is not to say that it is impossible to use a cumulative impact argument until the territory is entirely unusable. In West Moberly, the court found that the cumulative effects of an ongoing project and the historical context may inform the scope of the duty to consult. As Finch C. J. put it:

"The amended permits authorized activity in an area of fragile caribou habitat. Caribou have been an important part of the petitioners’ ancestors’ way of life and cultural identity, and the petitioners’ people would like to preserve them. There remain only 11 animals in the Burnt Pine herd, but experts consider there to be at least the possibility of the herd’s restoration and rehabilitation. The petitioners’ people have done what they could on their own to preserve the herd, by banning their people from hunting caribou for the last 40 years….To take those matters into consideration as within the scope of the duty to consult, is not to attempt the redress of past wrongs. Rather, it is simply to recognize an existing state of affairs, and to address the consequences of what may result from pursuit of the exploration programs."

It seems that West Moberly indicates that the scale of cumulative infringement is sensitive to cases involving both near and total extinguishment. But it still requires that there is a new infringement to trigger the cause of action. If the proposed activity does not substantially change the existing state of affairs, then there is no cause of action. Naturally, the question of what constitutes a “substantial change” is determined by judicial discretion on a case-by-case basis.

Aboriginal peoples are tasked with proving that their rights have been extinguished. By setting such a high threshold, the courts have effectively narrowed the remedy for cumulative infringement to damages.

The difference in the legal frameworks at play contribute to a death-by-a-thousand-cuts impact for Aboriginal peoples and the environment alike. In the Haida framework, the courts have limited their consideration of adverse impacts to the proposed project. As a result, Aboriginal peoples are left with the task of proving that the severity of a single cut is causally related to the proposed project. If this can be established, then West Moberly and Chippewas of the Thames hold that cumulative impacts can be considered as part of the general context. This consideration of cumulative impacts is still discretionary and highly variable, and courts have been somewhat inconsistent in their application, even in cases where present harm is proven. Whereas in the Sparrow/Badger framework, the courts have found that cumulative impacts can be considered in the infringement analysis, but the action does not arise until the impact has left “no meaningful right to hunt, fish or trap in relation to the territories,” as in Mikisew Cree. Thus, Aboriginal peoples are tasked with proving that, for all meaningful purposes, their rights have been extinguished. By setting such a high threshold, the courts have effectively narrowed the remedy for cumulative infringement to damages. Litigation relating to cumulative impacts continues, but at this point, there has been little indication that the courts will resolve the problem.

The Possibilities of UNDRIP

UNDRIP could be used to untangle the problem of cumulative infringement. This area of law faces many challenges because the perspective of Aboriginal peoples is understood as being a source of evidence but not law. As a result, the question of what constitutes an infringement and the threshold for barring further infringement is strictly in the hands of the courts. If Indigenous perspectives were interpreted as law by the courts, the processes for determining what constitutes an infringement would require that the courts balance the Crown’s environmental assessments with Indigenous assessments. This is a significant step away from the spectrum assessment in the DCA framework (which relies on judicial discretion to determine the significance of an asserted right) and toward a process based on Indigenous self-determination. It also would serve to provide a more balanced view of the constitutional status of the treaties.

While there are a multitude of different ways that UNDRIP could facilitate this shift, one of the more promising approaches is to consider article 27: “States shall establish and implement, in conjunction with indigenous peoples concerned, a fair, independent, impartial, open and transparent process, giving due recognition to indigenous peoples’ laws, traditions, customs and land tenure systems, to recognize and adjudicate the rights of indigenous peoples pertaining to their lands, territories and resources, including those which were traditionally owned or otherwise occupied or used. Indigenous peoples shall have the right to participate in this process.”

This requirement can assist the courts in balancing the skewed structure of Rio Tinto and Mikisew Cree. By directing the courts to consider the Indigenous law and land tenure systems, article 27 offers the possibility of a more balanced and impartial consideration of the historical impacts of resource extraction. This jurisdictional pluralism would have the generalizable benefit of introducing open and transparent standards for future extraction projects that prioritize the long-term sustainability of the environment for a diversity of uses.

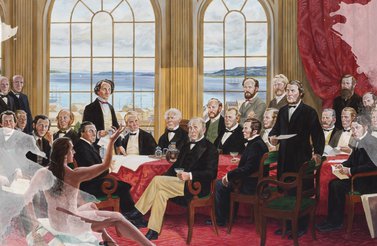

About the artist: Jim Logan has changed the content of his art a bit over the years; his work is a continuation of his exploration of the northern Canadian Indigenous experience. It’s his way of communicating in a polite and respectful way the realities of poverty, living within a hegemonic society and reconciling what “reconciliation” is or if one can really ever achieve it. In the painting “The Memory (it will be ok Mom),” Jim reflects on the psychological trauma of separation, abuse and cultural genocide that occurred in many residential schools, and the lingering generational effects on children of survivors.